By Kayleigh Howald

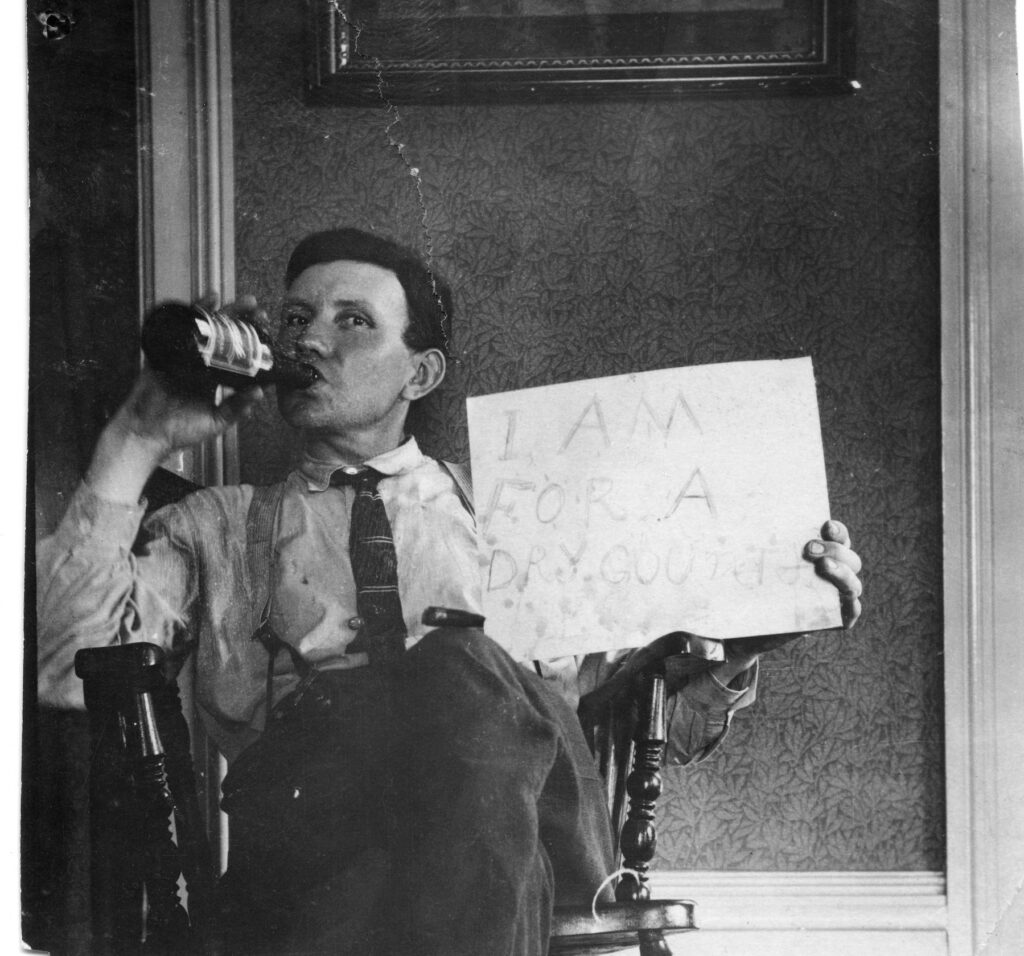

On January 16, 1919, the U.S. ratified the Eighteenth Amendment, officially prohibiting the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol in the United States. Yet, the period of prohibition – the Roaring ‘20s – is best known for its defiance of prohibition legislation and enforcement. This is especially true in Florida, which arguably flounced prohibition laws more than any other part of the country. In this blog, we will explore Florida’s unique history and position during prohibition as both an early adopter of temperance and a haven for rumrunners.

The Temperance Movement

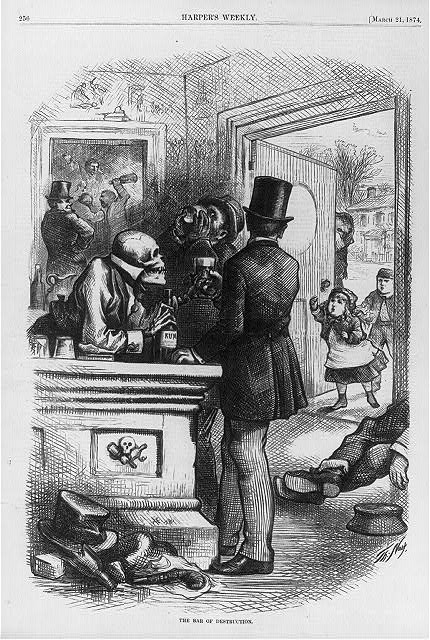

The Temperance Movement, an effort to limit or prohibit the consumption of alcohol, was a major social reform movement during the nineteenth century. Initially rooted in Protestant churches in the 1820s, the Temperance Movement quickly became known as “women’s crusade.” The language of temperance, such as literature and speeches, often focused on men’s behavior and how alcohol consumption impacted women, children, and the domestic sphere. Political cartoons depicted men spending their money in saloons, physically and verbally abusing their wives, children, and animals, and leaving families impoverished. The combination of religious sentiment and health considerations also appealed to the growing number of middle-class reformers immediately before and after the Civil War, many of whom were women.

At first, the Temperance Movement sought to moderate drinking, then to promote resisting the temptation to drink. Later, the goal became outright prohibition of alcohol sales. This shift coincided with a large wave of immigrants from southern, central, and eastern Europe, and some temperance advocates echoed the rhetoric of nativists, speaking against immigrants’ “wet” cultures and drinking customs. In addition, temperance advocates regarded urban saloons as hosts to a range of immoral behaviors beyond drunkenness, such as gambling, adultery, prostitution, profanity, and corruption.

The Anti-Saloon League and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) led the Temperance Movement in the United States. The Anti-Saloon League, founded in 1893, started in Oberlin, Ohio, but quickly grew to national prominence. The League was singularly focused on prohibition, leading them to work with any group, “including Democrats, Republicans, the Ku Klux Klan, the NAACP, the International Workers of the World, as well as many leading industrialists, including Henry Ford, John Rockefeller, and Andrew Carnegie.”[1]

The WCTU, on the other hand, fought for a variety of issues affecting women and girls. According to Carol Mattingly, “in addition to suffrage, they sought property rights for married women, the right to custody of children in divorce, and other reforms to assist impoverished and abused women and children.”[2] Further, the WCTU was instrumental in raising the age of sexual consent. As late as 1905, in five states (Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Maryland), the age of consent was only 10 years old. Prior to WCTU efforts, the age of consent in some states was as low as seven years. The WCTU also championed animal welfare. Throughout the United States, local WCTU chapters built water fountains to provide clean drinking water as an alternative to alcohol. Many fountains, however, included drinking troughs at varying heights for both horses and dogs.

The first WCTU chapter in southern Palm Beach County was established in Boynton Beach in October 1928. In addition to biweekly meetings, they hosted lectures, “intensive studies” of the Constitution, and essay contests. Some members of the Delray community supported temperance, particularly the editors of the Delray Beach News. In 1930, the News reprinted a story from the Melbourne Times commending the WCTU, stating, “Probably the greatest ‘evil effect’ of the Eighteenth Amendment has been the way it has ended the activities of the W.C.T.U., and kindred organizations, whose educational work made the Eighteenth Amendment possible. Teach the present generation of boys and girls just what is to be found in alcoholic beverages, and ten years hence we won’t need prohibition laws.”[3]

Temperance in South Florida

Florida was an unlikely area for the growing temperance movement due to its reliance on tourism and its steadily increasing population. Yet, certain individuals and groups shaped the state’s policies toward alcohol consumption through both land ownership and political clout. Miami, for example, was an early hub for temperance (ironic, given its later reputation as the “wicked city”). When Miami pioneer Julia Tuttle sold her land to Henry Morrison Flagler, they agreed on anti-liquor provisions in their deeds. The deeds specifically prohibited landowners from “buying, selling, or manufacturing” alcohol at the risk of having their land revert to the original owners. The only exception, however, was Flagler’s Royal Palm Hotel, which was permitted to sell alcohol during the tourist season.

While some historians argue this was Tuttle’s idea, Flagler biographer Edward Akin asserts that the stipulations may have originated with Flagler: “Flagler himself drank in moderation, but did not trust the lower classes with ardent spirits… As late as 1900, Flagler was uncompromising in his stand; but by 1902, although his principles had not changed, he gave up the antisaloon fight in Miami.”[4] After Julia Tuttle’s death in 1898, her son Harry became executor of her estate and sold a lot to a “prospective saloon keeper without the anti-liquor clause in its deed… After this action went uncontested, Harry Tuttle sold other lots without liquor clauses, some of which became sites of additional taverns.”[5] By 1908, there were eight saloons in Miami.

Despite the growing tavern business, local chapters of both the WCTU and Anti-Saloon League, as well as clergymen and the Miami Daily Metropolis newspaper, were influential in South Florida. They convinced city officials to enact pro-temperance laws, such as prohibiting taverns in residential areas, increasing fees for liquor licenses, and enforcing a state law banning the sale of alcohol to Indigenous people.[6]

The WCTU also held recruitment drives and arranged for lecturers to expound the “evils” of alcohol. In 1908, Carrie A. Nation – the hatchet-wielding temperance activist – visited Miami on invitation from the local WCTU chapter. Approximately 2,000 people attended Nation’s impassioned speech, while others had been on the receiving end of her criticism earlier in her visit. According to historian Paul S. George, Nation and two WCTU members visited bistros, saloons, gambling dens, and brothels on a “reconnaissance mission.”[7] Nation used this in her speech, where she produced a bottle of whiskey that was purchased on a Sunday, an illegal act at the time.

Nation’s findings and speech seemingly impacted Miami officials. Only a few months after her visit, they passed a tougher saloon ordinance which “reduced operating hours, placed restrictions on the size of the saloon district, called for the removal of any screen, frosted glass, or obstruction which prevented passers-by from seeing into saloons, banned women and children from bar premises, ordered saloons to close at ten o’clock on weeknights and midnight on Saturdays, and made it an offense to sell liquor to a drunkard or person already intoxicated.”[8]

Nation’s first visit to South Florida, however, occurred in 1904. Nation came to West Palm Beach and walked down Banyan Street, best known at the time for its saloons, gambling dens, and brothels. According to Eliot Kleinberg, city officials changed the street’s name from Banyan Street to First Street in the hopes of changing the area’s reputation (though many began simply calling the road “Thirst Street.”) It did not change back to Banyan Street until the 1990s.[9]

Prohibition Comes to the Sunshine State

During an election in 1913, a significant part of northern Dade County – including Fort Lauderdale, Dania, and Hallandale – voted to go “dry.” Voters hoped it would persuade officials in Miami to establish a new county, which would be able to focus more on the northern area’s more rural business interests. Temperance only won by 116 votes, however, due to low voter turnout. In a twist of irony, a torrential rainstorm kept many away from the polls, meaning rain was responsible for Dade County going from wet to dry. In 1915, Dade officials established Broward County. While it separated them from the teetotalers, Miami residents only had a few years to enjoy their libations. In 1915, the Florida Legislature passed the Davis Package Law, which banned establishments from selling both liquor by the bottle and by the drink. This essentially banned saloons throughout the state. In 1916, Florida elected Sidney Johnston Catts as governor. Catts, a nominee of the Prohibition Party, heralded in a new wave of temperance fervor in the state. In 1918, Florida ratified a state prohibition amendment, which went into effect on January 1, 1919, a full year before national prohibition.

Despite Prohibition, alcohol flowed freely during Florida’s infamous land boom. Developers often held large parties to help sell land, while many others kept alcohol in their back offices. Elected and town officials throughout Florida were also not immune to transporting illegal alcohol. In 1929, three men from Jupiter – Commissioner Rex C. Albertson, Chief of Police James Williams, and mechanic Frank Bolton – were arrested for “conspiracy to violate the eighteenth amendment” for transporting liquor “which had been left in or near Jupiter by bootleggers.”[10]

Prohibition in Delray

There are some hints that maybe Delray had its own moonshiners. In 1932, a 50-gallon copper still was found on the east side of the Intracoastal, two blocks north of the city park (now Veterans Park). According to a Delray Beach News report, “The equipment was in use for a period of time, possibly two years… The still, gasoline burners, and other equipment were concealed under ground [sic] in a cow pasture and garden. About 100 gallons of mash were at the still when it was found by the officers.”[11] Investigators never found the owner of the still, who seemingly abandoned it when they realized the site was being watched by the police.

In 1930, the police also found a large amount of alcohol during a raid. They brought it back to city hall, where Mayor Lysle W. Johnson ordered them to destroy it. There were also rumors of speakeasies in Delray Beach, but those rumors have remained unproven by historical evidence.

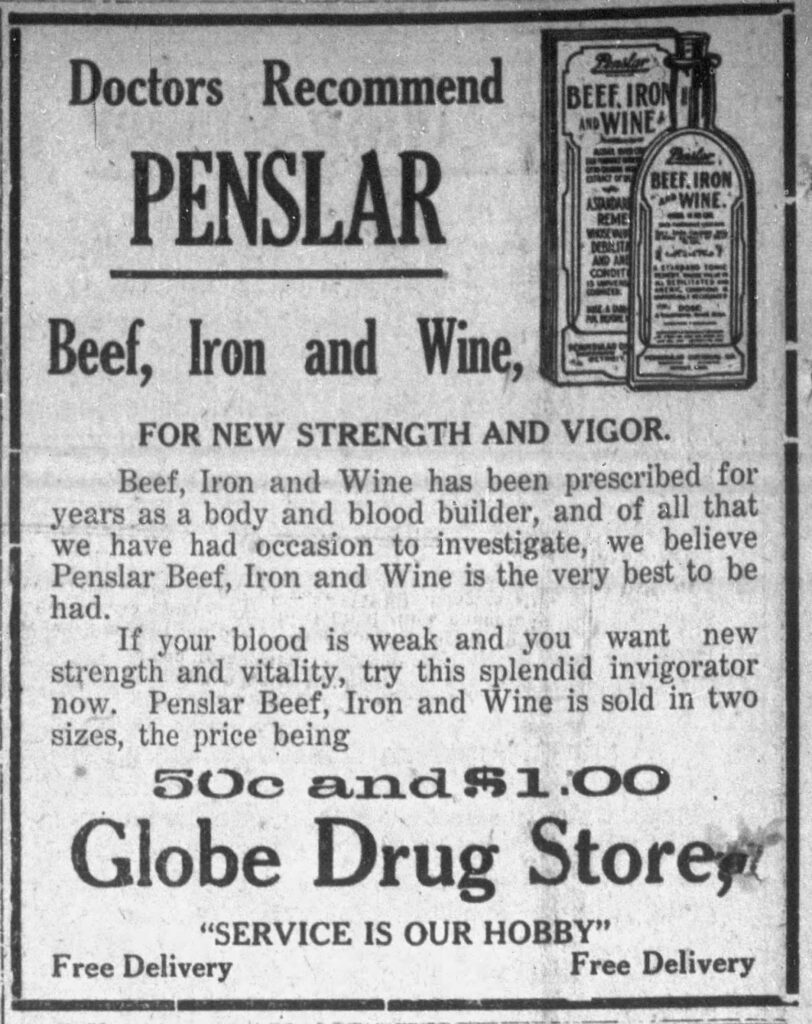

Delray residents found legal access to alcohol through Love’s Drugs, a pharmacy located on Atlantic Avenue. On Saturday nights, people flooded the pharmacy to purchase a tonic called Beef, Iron, and Wine. The tonic – which was meant to help with anemia and work as an appetite stimulant – contained “fresh beef juice, citrate of iron, superior imported sherry wine,” as well as just a touch of ethyl alcohol… approximately 19% alcohol by volume. During prohibition, it was so popular, Love’s Drugs often sold out.

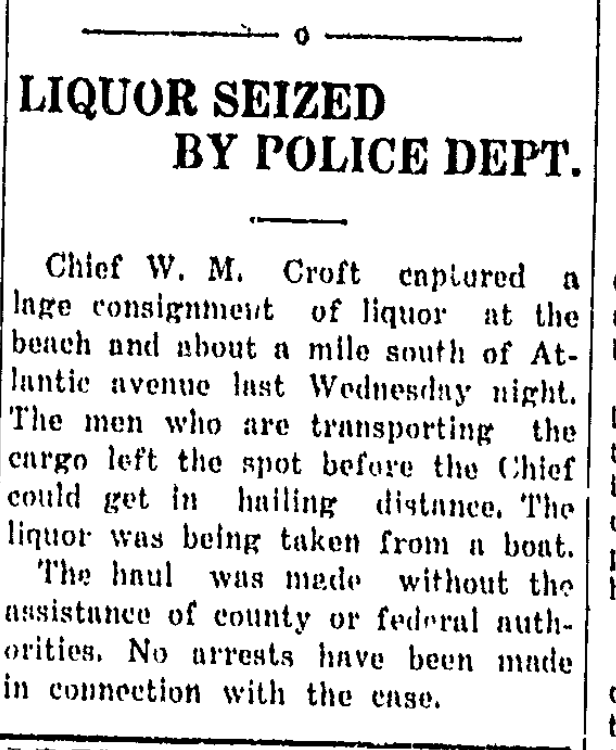

On numerous occasions, Police Chief W.M. Croft seized large supplies of liquor. In 1930, the Delray Beach police found “a large consignment of liquor at the beach and about a mile south of Atlantic Avenue.” The two men unloading alcohol from a boat spotted the officers and left “before the Chief could get in hailing distance.”[12]

In Delray Beach, many were jailed or put on work detail for possession of intoxicating liquor. Punishments for violating prohibition varied greatly and likely depended on the severity of the crime and the amount of liquor in one’s possession. Between 1925 and 1934, there were 169 arrests for drunkenness, 97 arrests for being drunk and disorderly, 89 arrests for the “possession of intoxicating liquor,” 18 for possessing, transporting, and selling, and 8 for selling. Based on these records, Delray residents and visitors were arguably more consumers than manufacturers, though there were a few recurring players defying prohibition through either possession or selling liquor. Many were Delray residents, but others were simply caught speeding through town. The Delray Beach News contains multiple reports of car chases involving individuals transporting alcohol.

Rumrunners: Buccaneers of the Jazz Age

Liquor smuggling was common on nearly every American waterway during Prohibition, including the Great Lakes, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Mississippi River. This was especially true along Florida’s east coast and the Florida Keys due to the proximity to Cuba and the Bahamas, where alcohol was legal. By 1921, rumrunning – maritime moonshining – became a lucrative trade. Rumrunners operated small, fast boats, outfitted to store whiskey, rum, and champagne from Cuba, the Bahamas, and other Caribbean islands to Florida’s still largely undeveloped coastline.

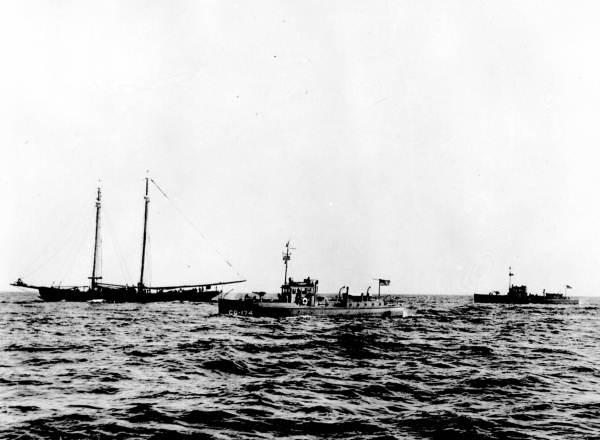

While some rumrunners picked up shipments from supply boats anchored three nautical miles offshore (and outside of U.S. Coast Guard jurisdiction), others simply sped past the understaffed and underfunded law enforcement agency boats. By 1923, the Coast Guard expanded dramatically, adding 200 cruiser vessels, ninety speed boats, thirty-six World War I naval ships, and nearly 6,000 personnel to enforce Prohibition.

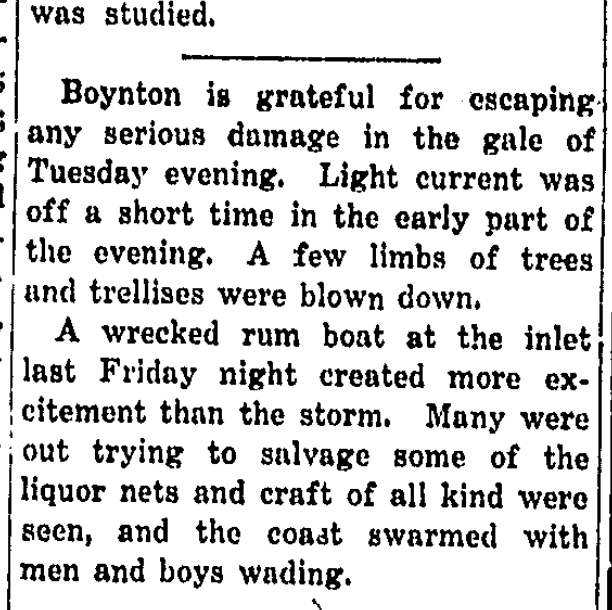

Numerous experienced sailors became successful rumrunners, such as William “Bill” McCoy. Many others, however, were far less experienced and often prone to mishaps. Therefore, it was not uncommon for bottles and crates of alcohol to simply wash ashore. For example, in 1928, the Delray Beach News reported a rum boat ran aground at the Boynton Inlet. Like wreckers and salvagers of decades past, locals quickly worked to retrieve the cases of alcohol with nets and boats, even wading into the surf.[13]

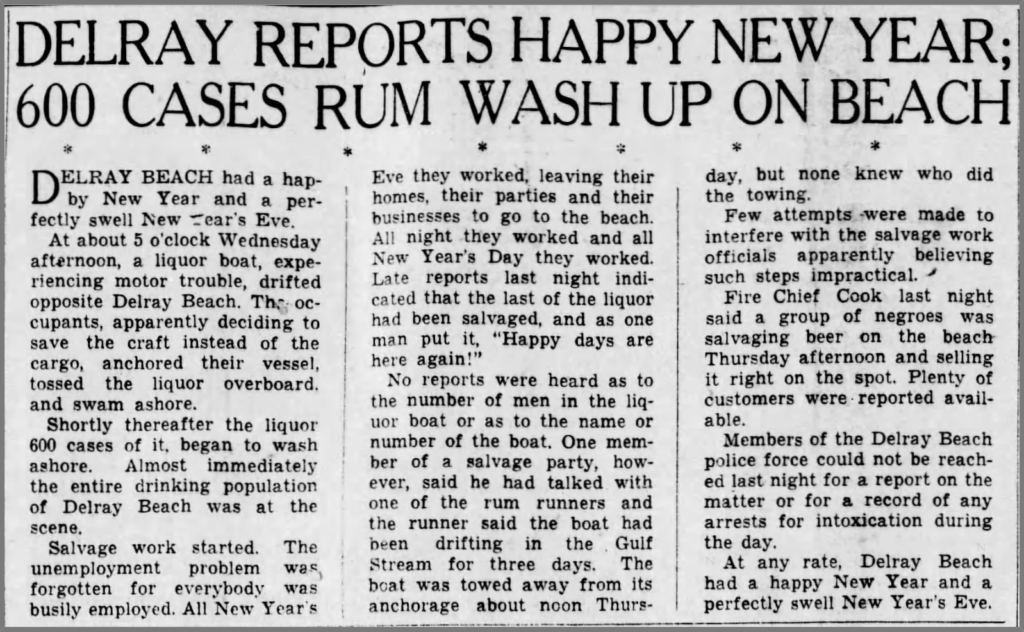

The most well-known story, however, occurred on New Years Eve: December 31, 1930. That night, a rum boat experienced motor trouble and drifted off the coast of Delray. The rum runners had a choice: save the cargo or save themselves; they threw the evidence overboard and swam to safety. As a result, approximately 600 cases of rum and beer washed on shore. The event was covered in the Palm Beach Post: “Almost immediately, the entire drinking population of Delray Beach was at the scene… The unemployment problem was forgotten about, and everybody was busily employed. All New Years Eve they worked, leaving their homes, their parties, and their businesses to go to the beach. All night they worked and all New Years Day they worked. Late reports [on January 1st] indicated that the last of the liquor had been salvaged, and as one man put, ‘Happy days are here again!’”[14]

The End of a Dry Spell

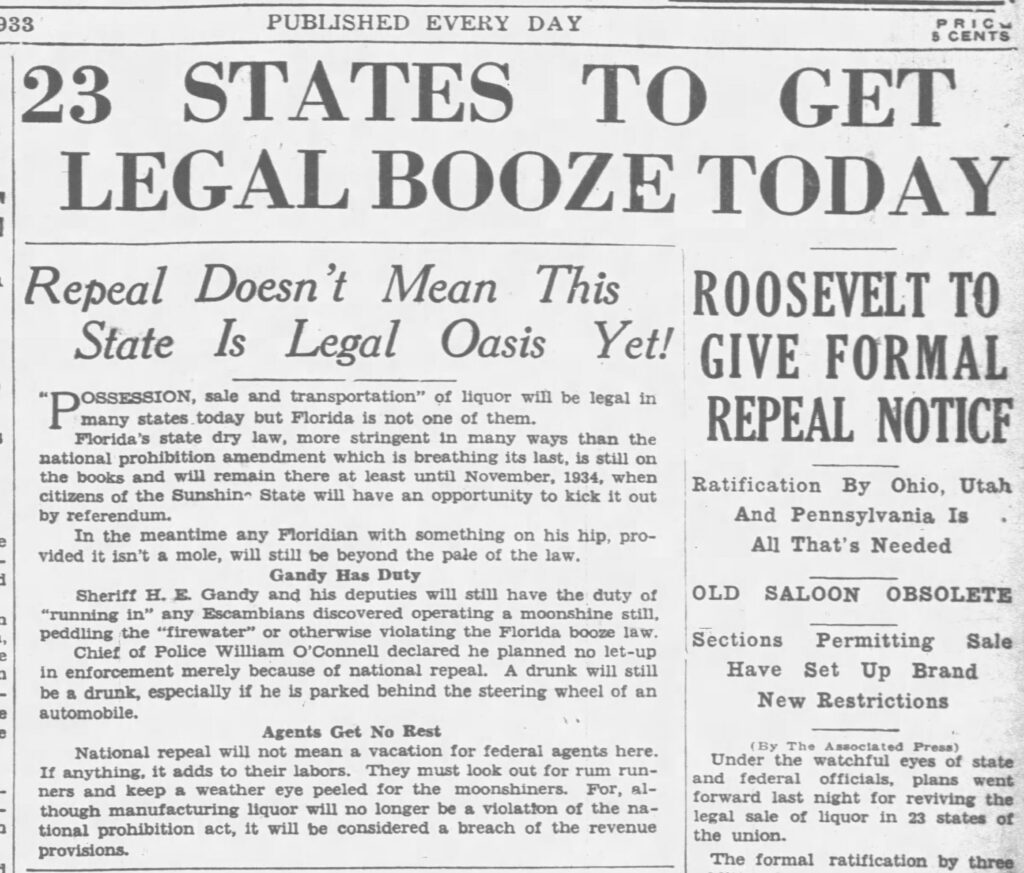

Prohibition officially ended on December 5, 1933, with the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment to the Constitution and the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment. While temperance organizations argued for prohibition to curb violence, by the end of the 1920s, many of the same people began arguing for repeal to protect families against the corruption and violence that resulted from Prohibition. In 1932, the Democratic Party’s platform included the repeal of Prohibition, with Franklin Delano Roosevelt campaigning on the promise of repeal. In Florida, delegates ratified the Twenty-first Amendment on November 14, 1933. The state law, however, was not repealed until November 6, 1934.

Although Prohibition ended in Florida in 1934, many counties remained dry. As late as 2005, Lafayette, Liberty, Madison, Suwannee, and Washington counties were the driest counties. It was illegal to sell any alcoholic beverage with an alcohol content above 6.234% by volume. In Calhoun, Hamilton, Holmes, and Jackson counties, package stores could sell alcohol, but it could not be consumed on the premises. Liberty County, located in the Panhandle, remains the only dry county in Florida. Lafayette County is partially dry, as it permits beer sales but disallows bars. The other formerly dry counties – Suwannee, Madison, and Washington – each voted to allow alcohol sales in 2011, 2012, and 2022 respectively.

So, the next time you enjoy a frozen rum runner or sip a glass of rosé on a summer day, it may be fun to think about how different – or, really, not so different – life was for many Floridians just 100 years ago.

For questions or comments, email the Archivist! [email protected]

[1] “The Verdict, Anti-Saloon League Flyer, April-May 1919,” Document Bank of Virginia, https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/dbva/items/show/229.

[2] Carol Mattingly, “Woman’s Temple, Women’s Fountains: The Erasure of Public Memory,” American Studies, no. 49 (2010): 134. https://journals.ku.edu/amsj/article/view/4009.

[3] “Encouraging News,” Delray Beach News, August 1, 1930.

[4] Edward N. Akin, Flagler: Rockefeller Partner and Florida Baron (University Press of Florida, 1992), 162.

[5] Paul S. George, “A Cyclone Hits Miami: Carrie Nation’s visit to ‘the Wicked City,’” Florida Historical Quarterly 2,no. 58 (1979): 150. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol58/iss2/4.

[6] Ibid., 151.

[7] Ibid., 155.

[8] Ibid., 159.

[9] Prohibition and the South Florida Connection (WLRN Documentaries, 2011).

[10] “Jupiter Town Officials Held in Prohibition Case,” Delray Beach News, July 5, 1929.

[11] “Big Still Found Near City Park,” Delray Beach News, March 4, 1932.

[12] “Liquor Seized by Police Dept.,” Delray Beach News, January 30, 1930.

[13] Clara White, “Boynton,” Delray Beach News, August 10, 1928.

[14] “Delray Reports Happy New Year; 600 Cases [of] Rum Wash Up on Beach,” Palm Beach Post, January 2, 1931.