By Kayleigh Howald

The Delray Beach Golf Club, located on West Atlantic Avenue, has provided Delray Beach residents with a local place to enjoy a round of golf for nearly 100 years. Throughout its surprisingly complex history, the course has seen changes in its surrounding landscape, its ownership, and its membership.

As August is National Golf Month, it seems like a perfect time to explore one of the city’s unique recreational amenities.

Demand Grows for Florida Golf

During the 1920s, Florida experienced the first of many land booms. Following World War I and the Progressive Era, Americans experienced new economic opportunities, allowing them both time and money to take vacations, travel in cars, and invest in real estate. Land speculation became popular for those inside and outside of Florida, causing land prices to increase dramatically. Tourism also became extremely popular, with many cities developing as winter resorts, including Miami Beach, Naples, and Marco Island.

Delray, though primarily an agricultural center known best for its tomatoes, beans, and other winter vegetables, also became a center for tourism, sports, and leisure. The town’s most iconic hotels/structures — the Arcade Building, the Alterep Hotel (now the Colony Hotel), the Bon Aire Hotel, and the Seacrest Hotel — were built during the 1920s. Delray also became the winter residence of several artists, cartoonists, and writers, such as Fontaine Fox and Nina Wilcox Putnam. In addition to winter tourists, Delray’s permanent population increased nearly 120% from 1,051 residents in 1920 to 2,333 in 1930.

Delray had an additional boost from nearby Gulf Stream, incorporated in 1925. In 1922, the Phipps family (descendants of Henry Phipps Jr., Andrew Carnegie’s business partner in the Carnegie Steel Company) started developing the land for a golf course and polo fields, attracting winter residents from Palm Beach and Miami. The Gulf Stream Golf Club opened in 1925 with a clubhouse designed by Addison Mizner and a course planned by famed Scottish golfer and architect Donald Ross.

The Early Years, 1923-1945

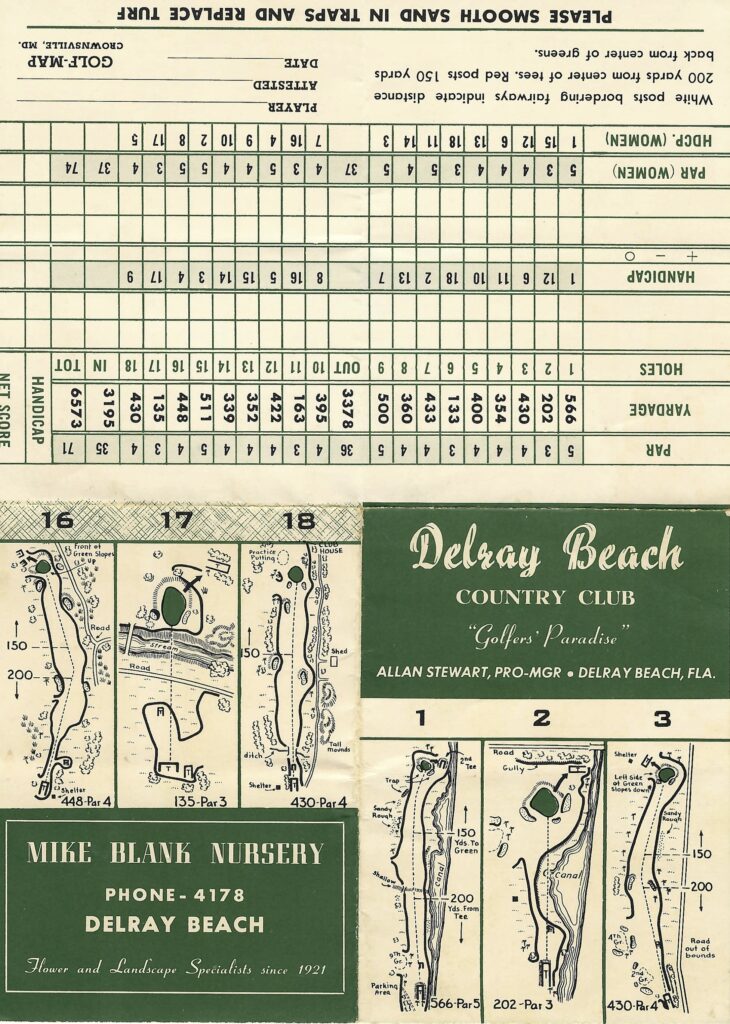

The increase in both permanent and temporary residents created the need for more recreational facilities in Delray. In addition to land for the city park along the Florida East Coast Canal – purchased for $10,500 in 1924 – the City purchased and constructed a municipal golf course between 1923 and 1925. On January 1, 1926, a nine-hole course, also designed by Donald Ross, opened for play.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the golf course remained one of Delray’s top attractions and recreational hot spots. Residents played during the winter months and throughout the summer, with the city offering reduced greens fees of only 50 cents per game from June to August. The club hosted tournaments and professional matches with prizes donated by local businesses. In 1929, for example, Adams Hardware Co. donated a Pfleuger ocean reel as a trophy.

Both local and state newspapers covered Delray tournaments, matches, and wins. Hole-in-ones by Delray residents were even reported as far as Tampa! In July 1929, the Tampa Bay Times ran a note about local banker Ollie Helland, who “joined the hole in one club by dropping his tee shot in hole No. 8 of the municipal golf course. He used an iron and his ball fell a few feet in front of the cup and trickled in. The hole is par 3 and has a water hazard.”

The course was often considered quite challenging, both due to the course and the native wildlife. In a 1927 match between Canadian Open champion and Gulf Stream Golf Club professional C.R. Murray and Delray professional Henry Ostro, the Delray Chief of Police shot an alligator in a water hazard. According to Canadian Golfer (1927), this stopped the “game for fifteen minutes.”

To maintain the course, the City established a golf committee to oversee its management. Their tasks included purchasing equipment and fertilizer, installing telephones, and initiating general improvements of both the clubhouse and greens. The committee included several notable city leaders, including first mayor John S. Sundy, Benjamin F. Sundy, E.M. Wilson, Clint Moore Jr., J.C. Keen, Dwight Bradshaw Sr., and J.B. Smith.

Like other neighboring golf courses, the club closed during World War II. When it reopened in 1945, there appeared to be a renewed interest in the course, coinciding with yet another land boom.

The Front Nine

After World War II, Florida entered a second land boom with many soldiers, families, and retirees relocating to Florida. In Palm Beach County alone, the population increased from 114,688 in 1950 to 348,993 in 1970. Delray’s population, specifically, rose from 6,312 to 19,366. To accommodate the new residents, the City once again looked to expanding the golf course.

In 1950, the City opened the second nine holes, designed by preeminent course architect Louis Sibbet “Dick” Wilson. Wilson had an extensive career before turning to architecture. A Philadelphia native, Wilson worked with designers Howard C. Toomey and William S. Flynn as a construction supervisor on a variety of projects, including the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, the Cleveland Country Club, the Indian Creek Club in Miami, and the Boca Raton Resort. According to an interview with Sports Illustrated in 1962, the Great Depression kept Wilson in Florida. “Building golf courses in Depression days was about as lucrative as peddling hard liquor to Mormons,” wrote golf sportswriter Herbert Warren Wind, “so Wilson found a job managing the Delray Beach Country Club and took small renovation jobs when he could find them. He camouflaged airfields early during World War II and launched himself into golf architecture on a full-time basis in 1945.”

The new course cost approximately $42,000 and Mike Blank oversaw the course’s construction. Blank, of course, was no stranger to golf courses. Tropical Golf Center, located on Federal Highway, was also known as the Mike Blank Golf Center.

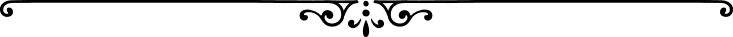

In 1952, a small group of regular players — all men over the age of 60 — formed the “Inner Circle.” The impromptu club began in 1949 when the men began gathering each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday morning to play. While they did not have formal competitions until 1966, the men began playing for prizes in 1957 when Wilson gifted them a dozen golf balls as trophies.

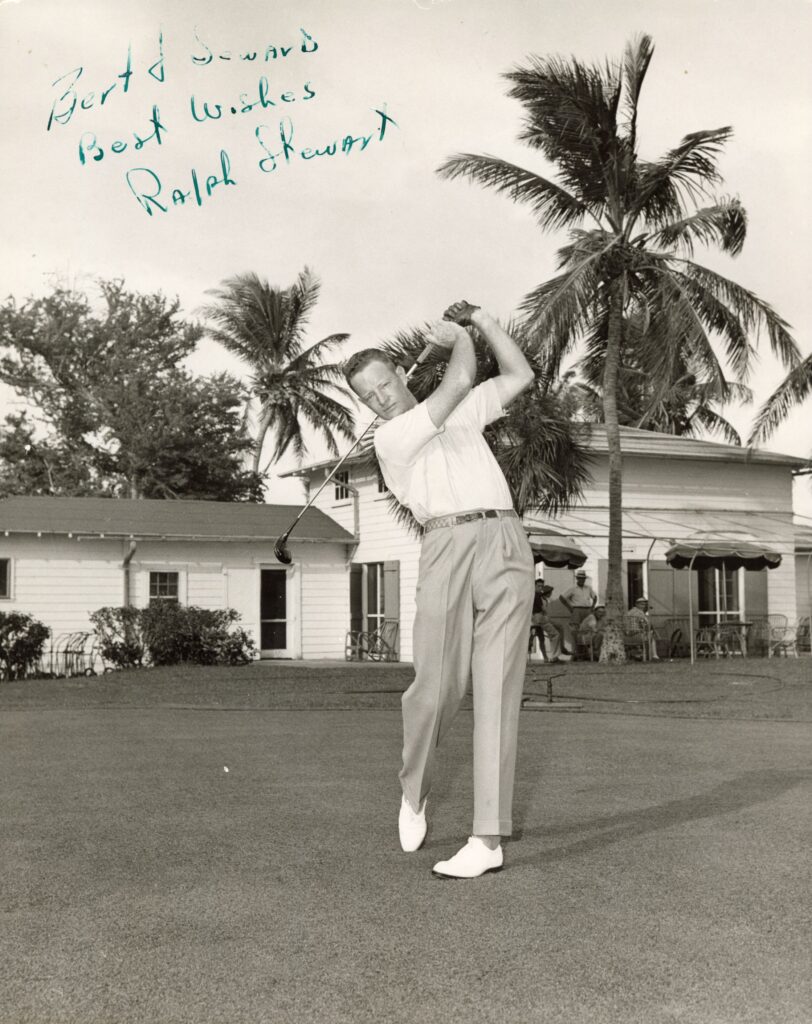

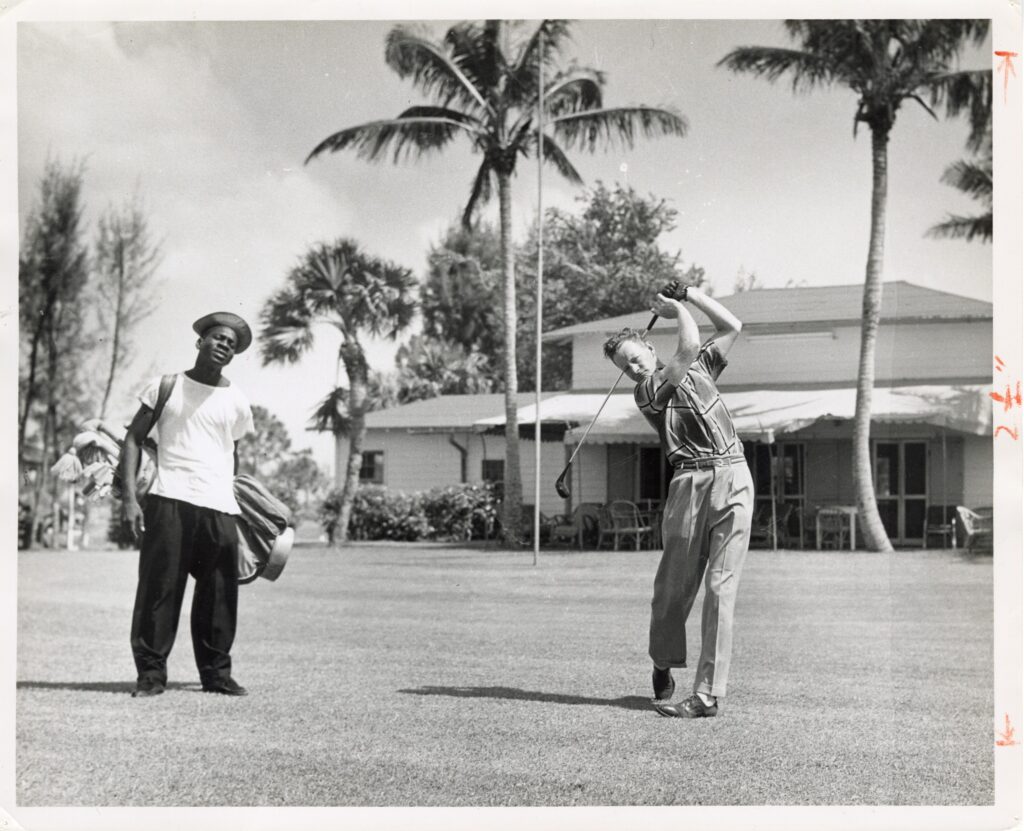

Professionals in Paradise

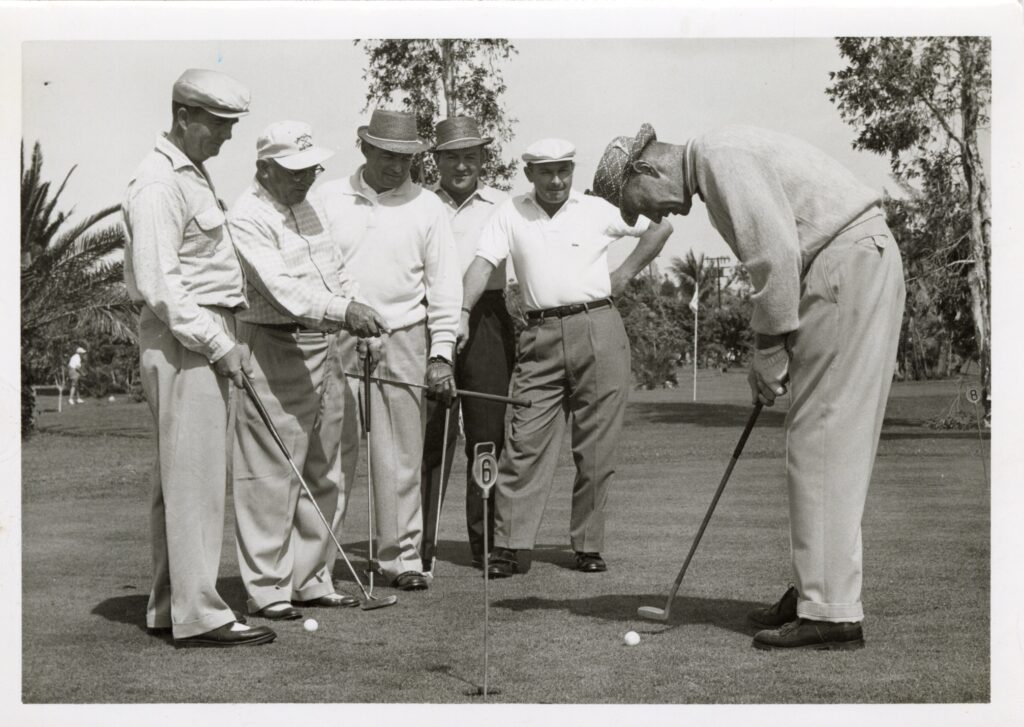

The Delray Beach municipal golf course was often frequented by golf professionals who would play through the first nine holes before heading down to Miami. They included Gene Sarazen, Tommy Bolt, Tom Creavy, and Walter Hagen.

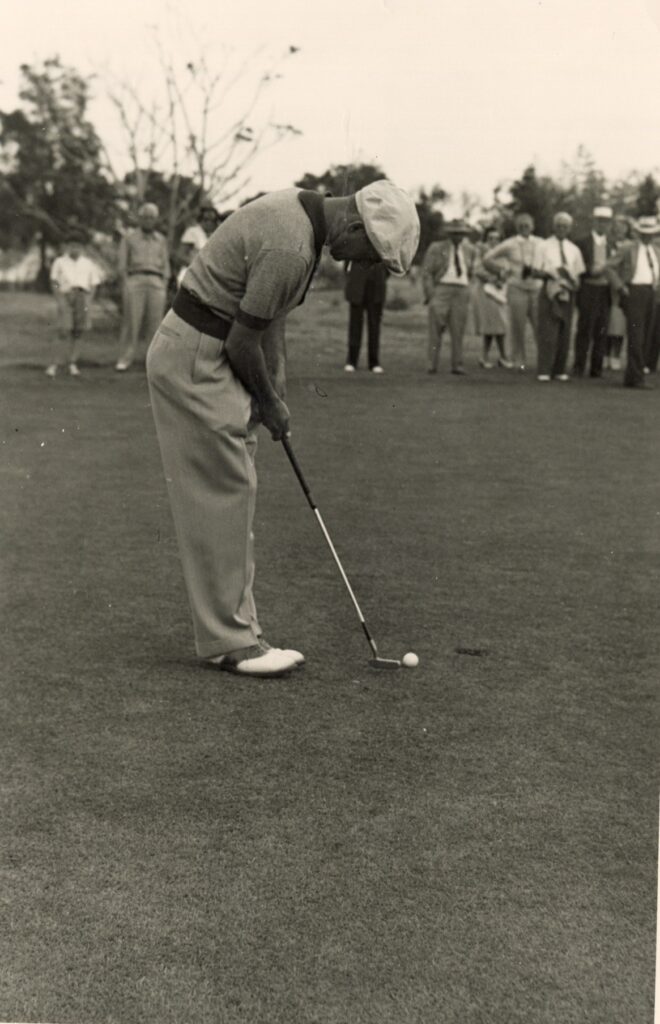

Toney Penna, a touring professional with MacGregor Golf Company and golf club designer, also played on the municipal course. Penna moved to Delray in approximately 1946 and lived across the Intracoastal from his longtime friend and Boca Raton Club professional, Tommy Armour.

Once Armour’s regular caddie at the Westchester Country Club in the 1920s, Penna often hit golf balls across the waterway, trying to make it into Armour’s backyard. Armour, of course, returned the favor.

According to the Florida Historic Golf Trail, during a dinner party at Penna’s house, a group of professional and amateur golfers wanted to see who could hit a golf ball “across the canal to Armour’s house, using his back window as the target. To make it harder they had to stand on one foot. After they marked the balls, they started sending them nearly 250 yards across the canal. Only one ball made it to Armour back yard and that was from Jimmy Demaret.” Armour, also known as the “Silver Scot,” served as a golf instructor at the Delray Beach club for approximately 15 years.

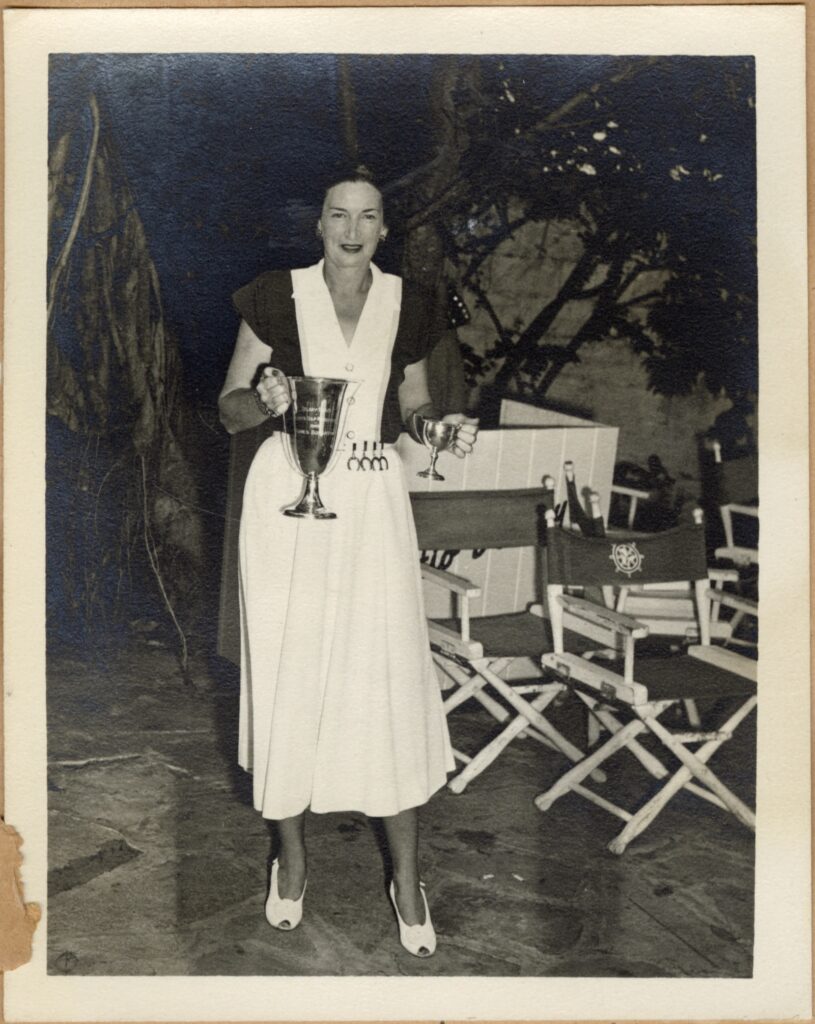

Women in Golf

Women in Delray were also avid golfers. By the 1940s, women joined the City’s golf committee and later formed the Delray Beach Women’s Golf Association. The organization participated in tournaments throughout Palm Beach County, often playing against other organizations from West Palm Beach and Lake Worth.

Members included Elizabeth McDaniel, Elizabeth Spencer, Eulalie Garner, Monna Van Kooy, Maria Nieder, Grace Stewart, Gladys Senior, Grace Nickell, Jeanette DeWitt, Dorotha Bauer, Elizabeth Doherty, Elsie Byrd, Cecilia Chace, Alberta McNeece, and Jessie Butts.

In March 1966, the golf club held the inaugural Louise Suggs Invitational, a golf tournament on the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour. While it was open to amateur players, they played against several top golfers, such as Marilynn Smith (winner of the St. Petersburg Open), Kathy Whitworth, and Gloria Armstrong. Suggs, an LPGA player and Delray resident, hosted the event for several years. Suggs also taught golf at the Delray Beach golf club as well as LPGA Hall of Famer Betty Jameson. In 1990, the course hired Sandra Eriksson, an LPGA Teaching & Club Professional member, to be head professional. Before arriving in Delray, Eriksson was the Director of Research for the National Golf Foundation and Regional Sports Director for the March of Dimes.

Golf and Jim Crow: Integration Prompts Sale

While the city-owned course made golf accessible to many Delray Beach residents, like most facilities in the Jim Crow South, it was far from equitable. After Brown v. Board of Education (1954) declared “separate but equal” legislation unconstitutional, schools and other public facilities slowly began to integrate across the country. This included beaches, parks, swimming pools, and golf courses.

In 1956, Delray Beach residents fought to desegregate the municipal beach and pool. When a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit against the city, citing testimony that there were no ordinances banning people of color from the municipal beach and pool, Delray’s Black citizens exercised their right to access the beach. After a group of angry white citizens attacked the group and threatened violence, civic leadership passed several “emergency ordinances” to curb racial violence, but these laws often disproportionally harmed Delray’s Black community. This included an outright ban of African Americans on the beach and municipal pool, police searches, roadblocks, and a resolution to exclude the entire Black district from Delray Beach’s city limits.

Although city leadership agreed to drop the exclusion resolution after a televised meeting with the Delray Beach Civic League, the tumultuous summer of 1956 seemingly influenced the sudden sale of the golf course in 1957. Several local newspapers, including the Delray Beach Journal, Palm Beach Post, Fort Lauderdale News and The Miami Herald, pointed to integration as a key component of the City’s decision. “The proposal to sell the golf course to private individuals is interpreted as a move by the city to prevent use of the course by Negroes,” the Palm Beach Post reported. “Private ownership of the golf course has been suggested as a method of regulating use of the course.”

According to Fort Lauderdale News reporter Bill Beck, commissioners and city officials often agreed – off the record – that the major reason for the sale was to “avoid any possible racial controversy. Yet, when the question was asked ‘What weight did integration have in the decision to sell?’ it prompted only a chorus of ‘let’s not talk about’ and ‘no comment.’” Officials cited the construction of the new City Hall and general improvements throughout the city as the reason for the sale.

The Delray Beach Journal expressed a similar opinion in an October 1957 editorial. “While it will probably never gain any official recognition, the main reason advanced for disposing of the golf course to private ownership is to avoid eventual integration.” The Journal, however, also believed “integration may be forestalled for many years. It is possible there could be even a reversal in the present trend.”

The Grimes Foundation Takes Over

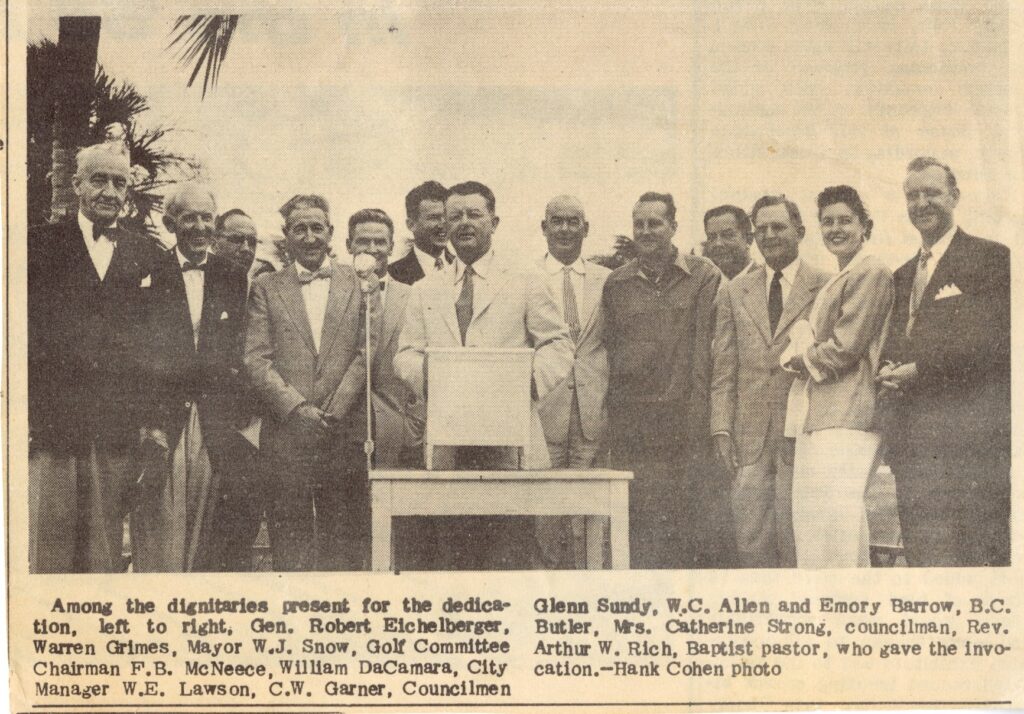

In September 1957, airplane lighting inventor and philanthropist Warren G. Grimes offered the lone bid to purchase the golf course for $350,000 (approximately $3.9 million today). Under the terms of the deed, the land could only be used as a golf course and recreation center for 50 years or it reverted to the city; the city had the right to repurchase the course 20 years after the transfer of ownership; and the city had the right of first refusal to any potential sale within that 20-year period. During later negotiations, the Grimes Foundations insisted the word “private” also be included in the deed, insisting he was trying to “save the city from a problem.”

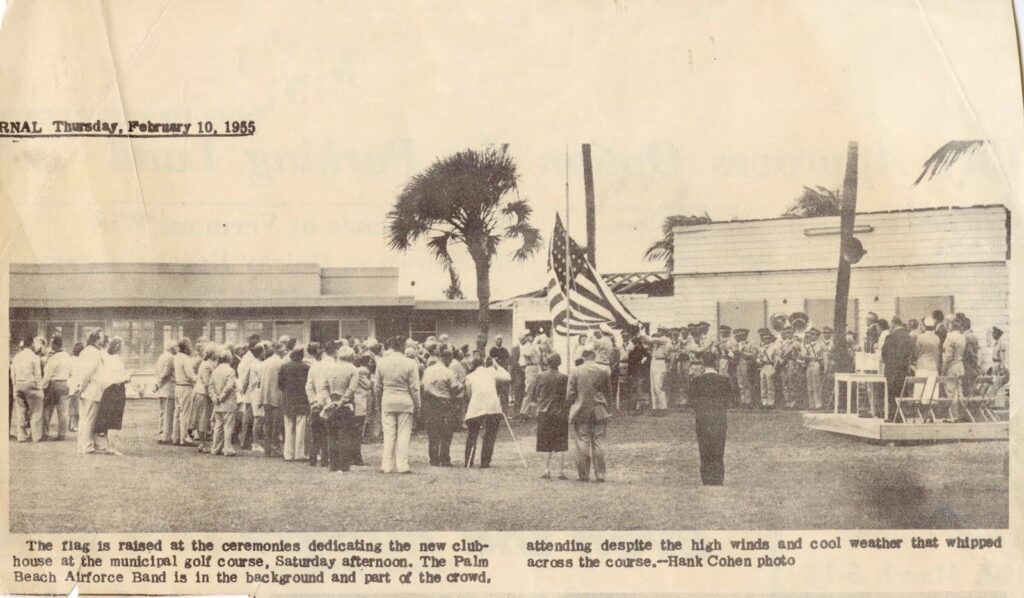

People are often surprised by Grimes’ involvement with the golf course. Instead, Grimes is best known for his contributions to Delray Beach, including sponsoring the city’s July 4th fireworks display over Lake Ida and the Christmas Tree on the beach, donating land to Bethesda Hospital, and regular contributions to the library. In a July 1957 telegram to the Delray Beach Journal, Grimes noted his Foundation also lent the city $100,000 for the golf course’s 1955 clubhouse and to pay off past debts on the course. While the loan carried 3% interest, the interest paid by the city was then donated by the Foundation to the public library. Grimes insisted any profit made by the golf course would be used for “charitable or educational purposes” within Delray Beach.

Several residents were vehemently opposed to the sale. In August 1957, former commissioner and city attorney Neil E. MacMillan circulated a petition against the sale, noting:

“Land is gold. Large tracts are unobtainable and small tracts are scarce and expensive to replace. The land comprising the golf course, in event of discontinuance of the golf course in the future, would be needed as a large public park or for other public municipal purposes not yet foreseen. To sell the land now at any price would ‘sell out’ the heritage of our children. Our city is perpetual and its assets should be preserved with this in mind.”

The petition was backed by former city commissioner John Kabler, former city commissioner and business owner W.C. Musgrave, and planning and zoning board member James I. Sinks. Their comments focused heavily on the scarcity of land within the city and the need to preserve land as the city grew, a notable concern amid the population and land boom. The petition inspired the Chamber of Commerce to conduct a poll of its membership and the Kiwanis Club to study aspects of the proposed sale. The Delray Beach Journal also expressed opposition.

During a commission meeting in late August 1957, the commission decided to hold a referendum in November, allowing taxpayers to vote on the transfer of ownership. Following the meeting, the Grimes Foundation began a newspaper and mail advertising campaign, hoping to persuade voters to support the sale. They also met with the local Golf Association, who gave “overwhelming support to the sale.”

The Women’s Golf Association was also in favor, explaining the club would remain under control of committees elected by club members and annual tournaments would continue. Their campaigns, it seemed, ultimately worked. On November 5, 1957, 1,361 out of 1,800 freeholders voted in favor of the sale. After several months of contentious negotiations over details of the deed, the city finally delivered the deed and title to the Grimes Foundation on March 21, 1958.

The Delray Beach Country Club

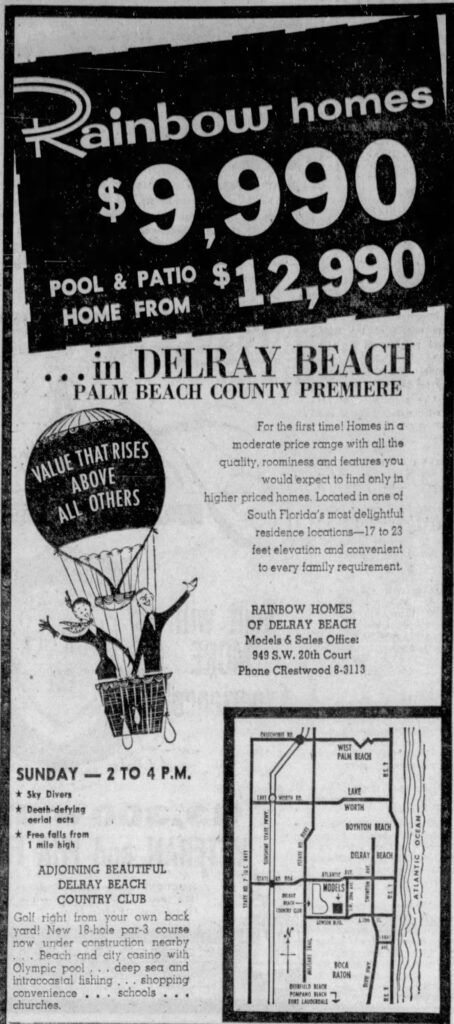

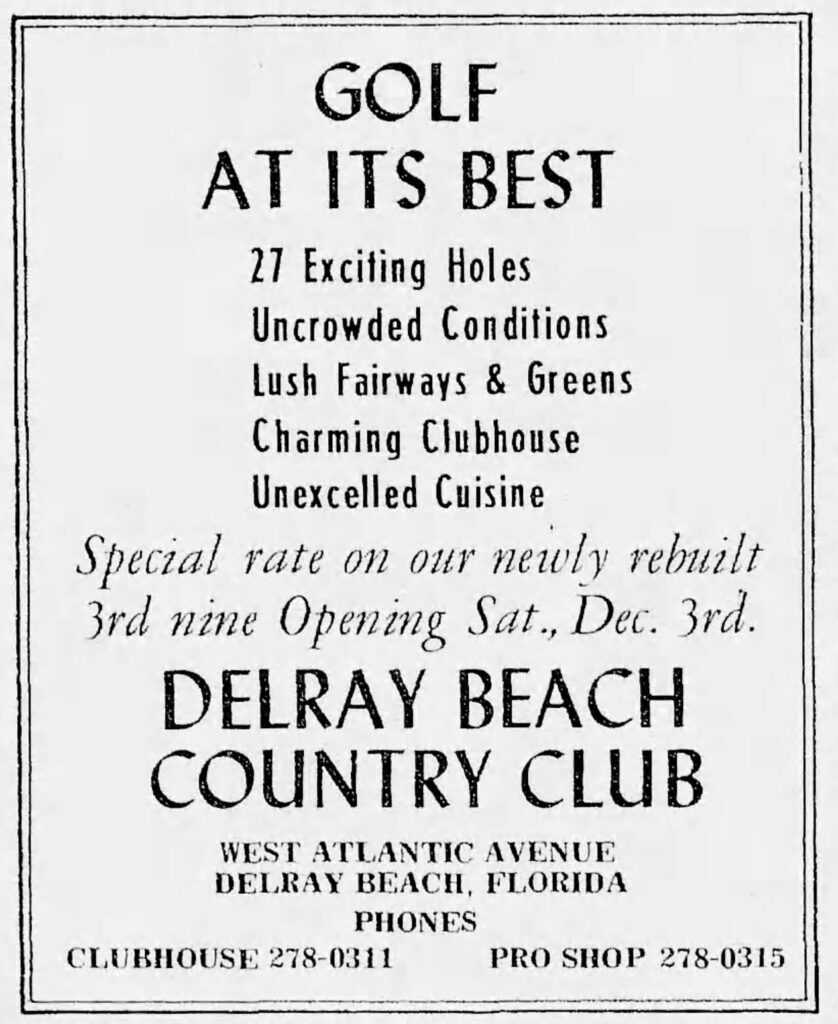

For the most part, the Grimes Foundation’s ownership of the golf course changed very little. The course and clubhouse continued to hold tournaments, wedding receptions, political events, and fundraisers (including a “brunch-eon” fashion show). Housing developments along West Atlantic Avenue also took advantage of the proximity to the Country Club, often utilizing it in advertisements.

The only major disagreement that arose between Grimes and the city commission occurred over three trailers/mobile homes on the property. When the clubhouse and new pro shop were robbed twice in less than a week, Grimes wanted to install mobile homes to house the club’s security personnel. The city denied his request, citing a new ordinance prohibiting trailers within city limits. Grimes declared the city had a “moral responsibility” for any future thefts and even proposed a lawsuit to remove the course from city limits if he was not granted a variance. Eventually, in March 1961, the city conceded to Grimes, who, in return, provided all the sod and soil needed for landscaping the new City Hall grounds.

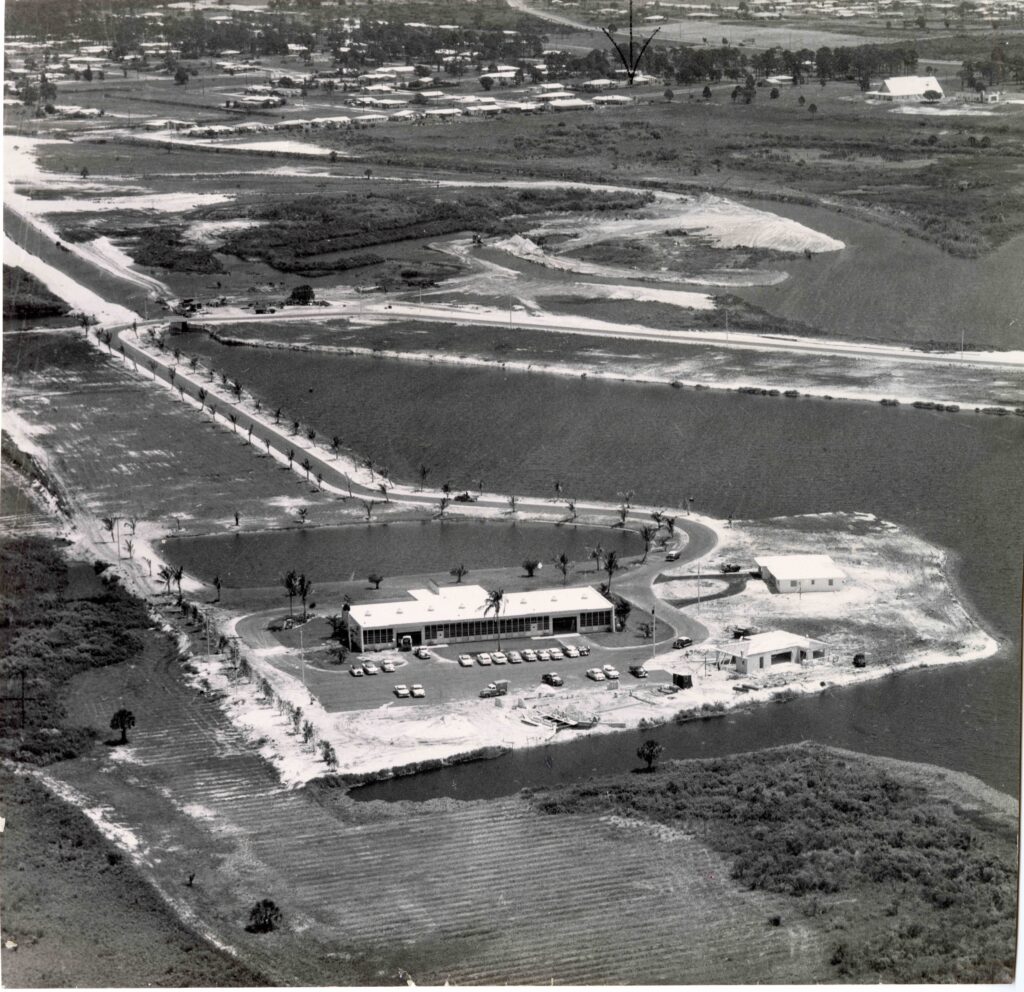

In addition to new security and course improvements, Grimes also worked to expand the course. In 1961, he acquired over 42 acres and hired Robert Lawrence to design a “third nine,” creating a 27-hole course. The third nine opened on January 15, 1962, and featured Ormond Bermuda grasses and Everglades No. 1 strains. Management also planted 1,000 palm trees and melaleuca trees, the latter of which is now considered an invasive species.

R.W. McDowell and Robert Bruce Harris

In February 1964, the Grimes Foundation requested to sell the golf course. The bidder was R.W. “Rollie” McDowell, a Fort Lauderdale man who owned similar properties. Although rumored to be “representing a Chicago syndicate of golf course operators,” according to the Palm Beach Post, McDowell’s attorney denied those accounts. After the city declined repurchasing the course in early March, McDowell bought the club for $500,000.

McDowell quickly began refurbishing the clubhouse and greens. He replaced the framework and jalousie windows with concrete blocks and plate glass; added a tap room, patio, and covered walkway; and installed air conditioning throughout the clubhouse. By October 1965, however, McDowell went before the commission and notified them about his intention to sell the club again for $563,500.

This time, in November 1965, the golf course was purchased by Robert Bruce Harris, a Chicago-based golf course architect. Harris was well-known in southern Palm Beach County golfing circles. In addition to his two golf courses in Chicago, Harris established and designed the Country Club of Florida in the Village of Golf, a small municipality just west of Boynton Beach. (An interesting fact: while the city was considering repurchasing the course, Harris was designing a new golf course in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin for Playboy.)

During his tenure, Harris made the course “semi-private.” This meant the new ownership would accept private memberships, but guests of club members could play on a greens-fee basis. Harris owned the property until his death in 1976. After his death, ownership passed to his wife, Elizabeth Harris through their company, Florida Golf Club, Inc.

The Municipal Course

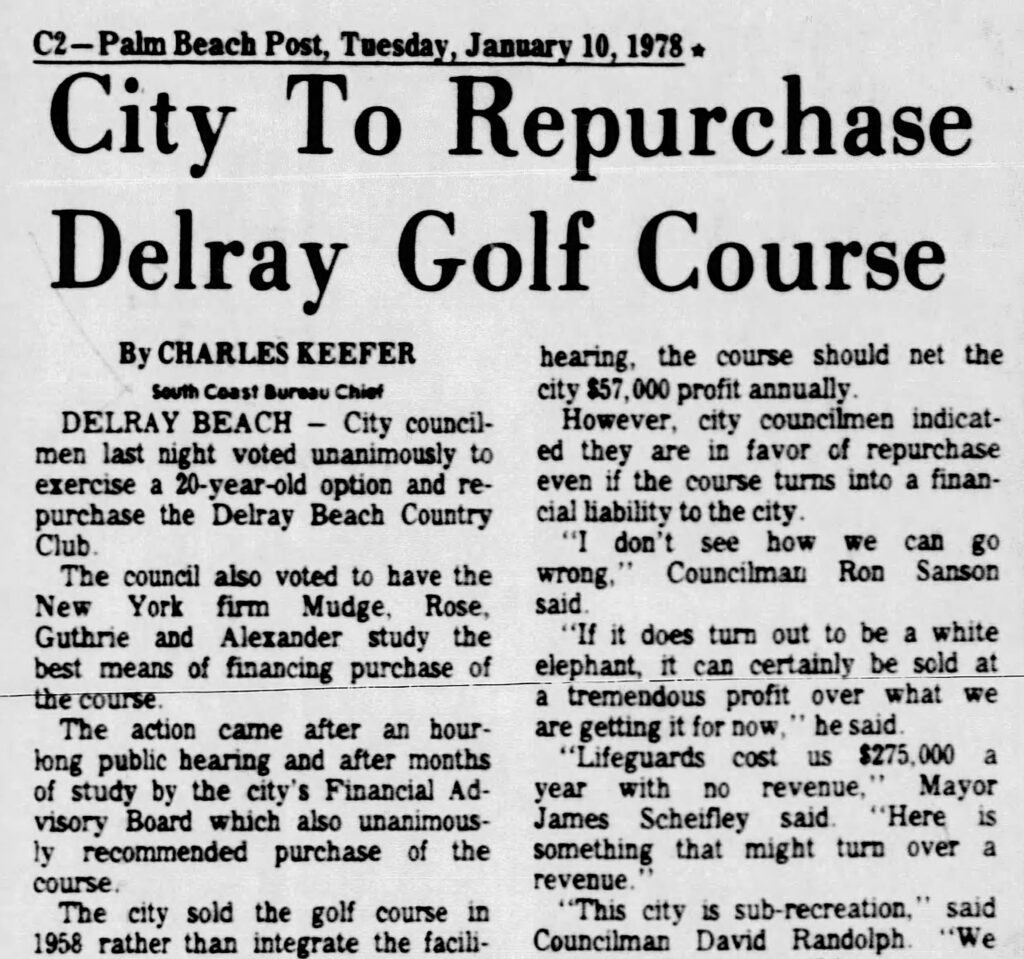

By 1977, the Delray Beach Country Club was in dire straits. The course had not been actively maintained following Harris’ death and the pro shop was still not air conditioned. While the city had a chance to repurchase a section of the course in 1973, the $3.7 million price tag was deemed too steep. City leadership, including avid golfer and former mayor Jim Scheifley, recognized they could repurchase the course beginning on March 21, 1978 and bring a public course back to Delray Beach.

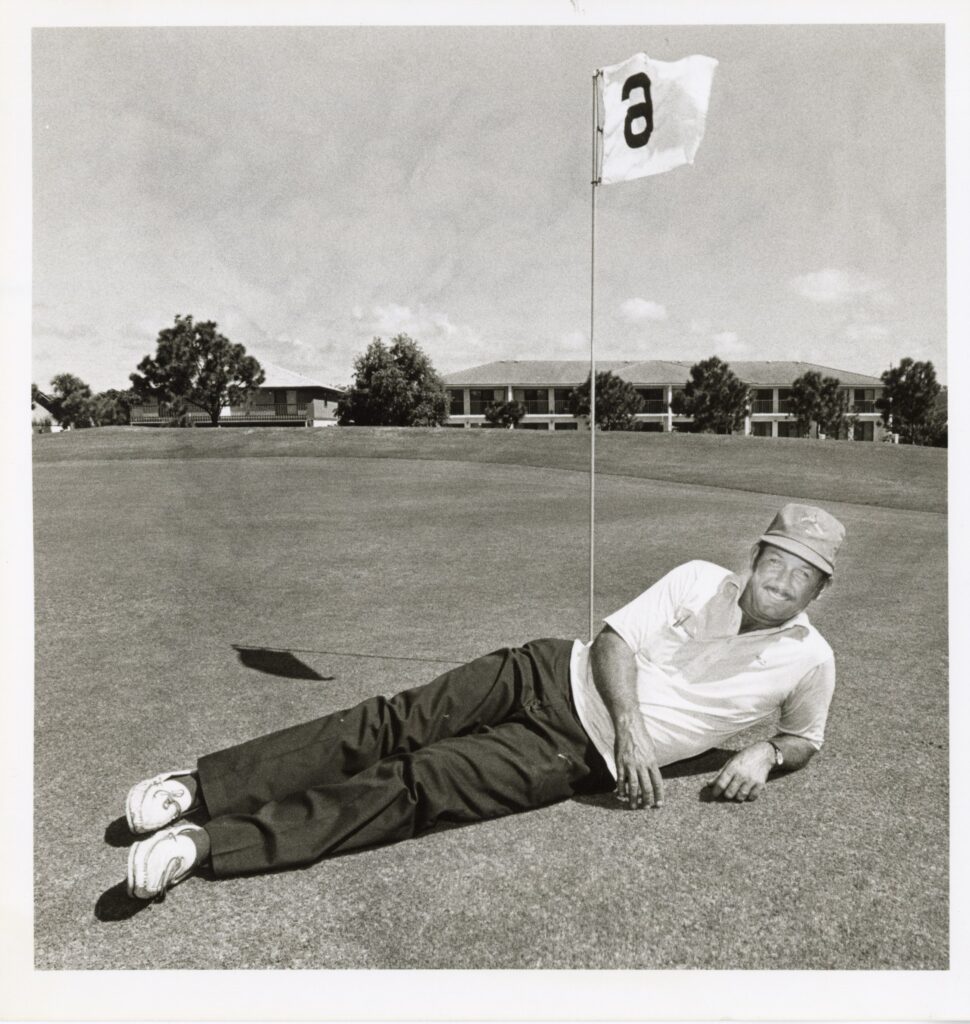

On February 1, 1979, the city officially purchased the 18-hole golf course from Elizabeth Harris and Florida Golf Club Inc. for $2 million in municipal bonds (Harris sold the third nine at an earlier date). Approximately $1.5 million went toward the land and $500,000 funded rebuilding the greens, replanting fairways, installing an automatic sprinkler system, improving the clubhouse, and buying golf carts. In June 1980, the city hired Frank Clark as manager of the municipal golf course. Clark was commended by golfing associations for his improvements, particularly installing rain shelters with emergency phones and first aid kits.

Delray Beach Golf Club, 1994-2024

The municipal course’s past thirty years have seen numerous changes and growth. In 1995, the club opened a new $2.2 million clubhouse designed by local architect Digby Bridges. The grand opening ceremony was well-attended by both city officials and golf professionals, including Betty Jameson, Louise Suggs, Tommy Armour, golf course architects Alice and Pete Dye, former mayors Jim Scheifley and Leon Weeks, and longtime Delray golfer Stuart Weeks.

In 2000, the US Golf Association named the Delray Beach Golf Club “one of the finest public golf courses in the nation.” In 2003, under Eriksson’s direction, the course underwent significant improvements, such as the installation of TifEagle, a more heat resistant strain of grass, on all 18 holes. In recent years, the course was featured on the Florida Historic Golf Trail, which highlighted the club’s notable professionals and Donald Ross-designed back nine. The city also faced another prospective bid for a portion of the course, but ended when citizens voiced their concerns over development of the green space with arguments that echoed those of the 1958 sale. In June 2023, the Delray Beach City Commission unanimously agreed the course should be listed on the local Register of Historic Places.

As the history of the municipal course suggests, it has undergone many changes over the years. Yet, despite its variations, it remains the site of memories and stories from longtime Delray Beach residents and golf players, and one of the relatively few public golf courses in Palm Beach County. This National Golf Month, be sure to enjoy a good walk (and perhaps a few rounds of golf) on Delray’s historic course.

For questions or comments, email the Archivist! [email protected]