By Kayleigh Howald

Agriculture remains one of Florida’s top industries alongside tourism, aviation, life sciences, and manufacturing. For newer residents of Delray Beach and coastal Palm Beach County, it may be nearly impossible to imagine the vast array of fields and orchards that dominated the soil along our busy thoroughfares. Even thirty years ago (when my family first arrived in Palm Beach County), there were far more farms, grazing pastures, and rural spaces amidst the suburban sprawl. Yet, the history of farming and agriculture in Delray remains central to the city’s development and its most well-honored traditions.

The Town of Linton

Delray Beach’s agriculture, like much of the east coast of Florida, developed along the rapidly constructed railways and canals. In 1854, Florida’s legislature created the Internal Improvement Fund (IIF) to manage the sale of public lands and approve infrastructure construction. This, however, did not take into consideration the thousands of African Americans, Seminole Native Americans, and Black Seminoles who were already living in South Florida.

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the IIF granted millions of acres to transportation and land companies, such as the Florida Coast Line Canal and Transportation Company, the Boston and Florida Atlantic Coast Land Company, and, most notable, the Florida East Coast Railway Company (FEC). Through the IIF and his acquisition of other companies’ lands, oil magnate Henry M. Flagler obtained so much land, he was unable to manage all of it. In 1896, Flagler established the Model Land Company, and installed James E. Ingraham, former executive for Henry S. Sanford’s South Florida Railroad Company and Everglades surveyor, as Land Commissioner for the new division. Avid students of early Delray history will recognize Ingraham’s name: SE Second Avenue was once named after him!

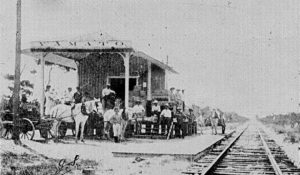

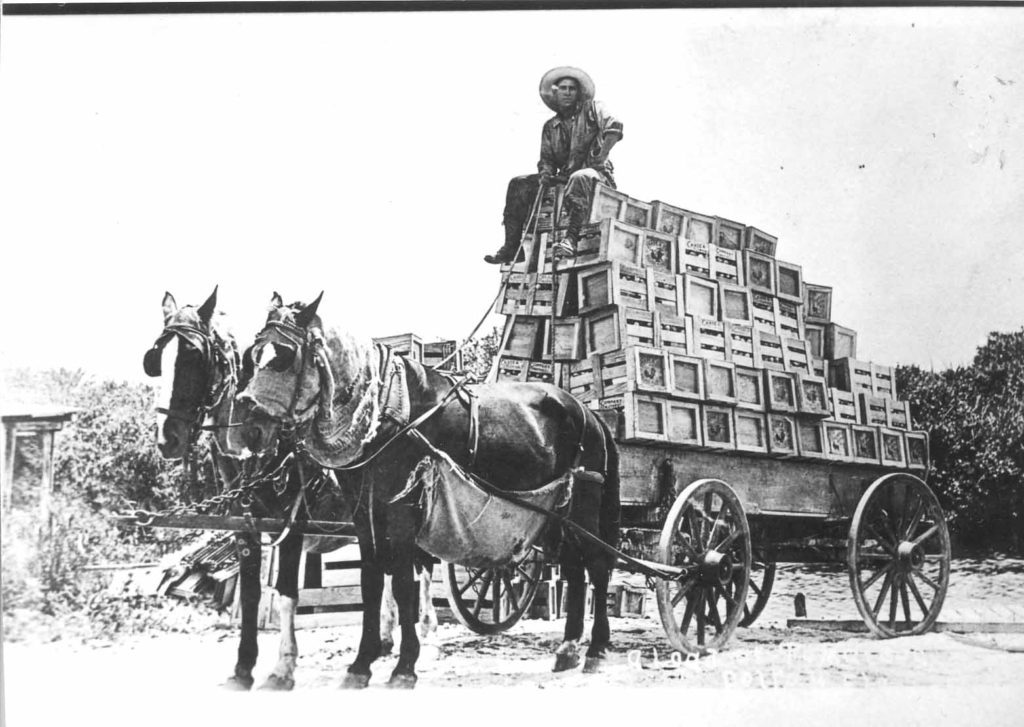

In 1894, several Black families from Florida’s Panhandle and the Bahamas purchased land from the Florida East Coast Railway, becoming the first non-Native settlers to Delray Beach. These pioneers – including Jane and Fagan Henry, Joseph and Estella Hanna, Joseph Green, James and Nellie Monroe, Joseph Smith, and Ed Smith – developed the land quickly, established schools and churches, and harvested winter crops. When Delray’s first white settlers arrived via the Model Land Company, they also set up homesteads and began establishing farms. The proximity to the railroad line allowed farmers, like Adolf Hofman, Peter Pedersen, J.L. Priest, A.T. Tasker, and C.H. Miller, and Leo Zill, to establish truck farming in Delray. Following a few years of freezes, Delray became a major producer of staple market garden crops, such as celery, cabbage, strawberries, squash, cucumbers, potatoes, pumpkins, and tomatoes. It also became a famous producer of Florida-specific produce, namely citrus, mangoes, and, of course, pineapples.

The Palm Beach County Fair

By 1913, Delray was so well-known for its produce, the town hosted the second annual Palm Beach County Fair. There, Delray’s farmers and residents took home top prizes for various fruits, vegetables, flowers, baked goods, and artwork. For his display, likely designed by his daughter Annie, Adolf Hofman won the Flagler prize of $100 for best general exhibit. Peter Pedersen won prizes for best vegetable display and best peppers, while J.L. Priest won first prize in five varieties of sweet potatoes. Priest, along with Leo Zill, also won prizes for their tomatoes. According to a report in The Tropic Sun, Delray women also swept the baking prizes: Mrs. J. Wuepper for bread; Mesdames Zeder and Eliasen for crullers and cookies; Mesdames J.S. Sundy and Wuepper for pies, and Mesdames Acton and Sundy for cakes. Mrs. Wuepper also received first prize for “best display of cakes for all varieties.”

Top Crops in Delray Beach

For decades, pineapples were the most well-known crop in Delray Beach, with many families maintaining small patches in their yards. By 1916, however, disease, water drainage, and market competition impacted east coast pineapple crops and pineapples gradually disappeared from Delray’s farms. Tomatoes, however, became a successful crop in Delray and the surrounding areas. Delray Beach produced so many tomatoes, T.A. Snider, a winter resident, opened a ketchup (or catsup) and soup manufacturing plant in the town. Through Snider’s Catsup, locally grown tomatoes were enjoyed nationwide.

While tomatoes and other truck crops remained staples of Delray Beach’s agricultural landscape, in 1939, another unique crop became a town symbol: gladiola flowers. Gladioli grow best with warm days and cool nights in sandy soil, and require very little water, making South Florida the perfect climate for the flowering plants. During the mid-twentieth century, Delray Beach became the leading source for gladiola flowers in the United States. Thirteen growers managed 1,600 acres and produced approximately three million gladiola bundles per year. These farmers cultivated fourteen varieties of gladiola, including the Red Charm, Phantom Beauty, Snow Princess, Margaret Beaton, Elizabeth the Queen, and Spotlight.

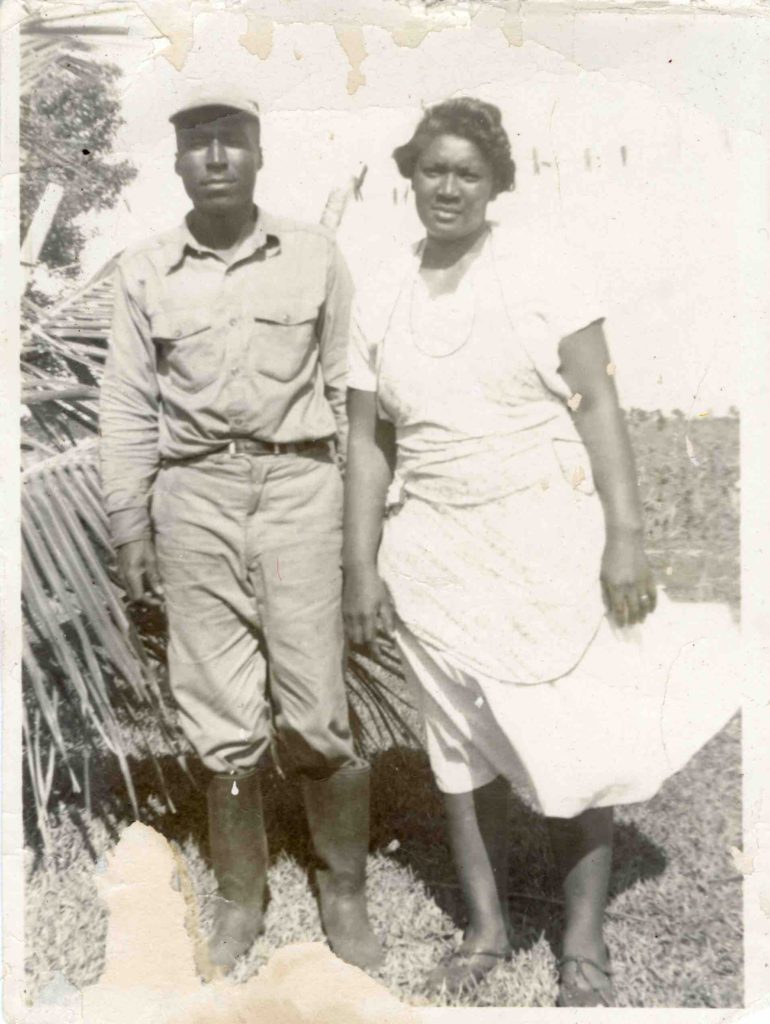

One of the leading farms was Everglades Flower Growers. Owned and operated by Charlie and Essie Mae Massengill, it was the only Black-owned gladiola farm in Delray Beach. In 1950, the Massengills began sharecropping on the land, then owned by Roy and Bennetta Polatta. In 1964, the Massengills bought the property and expanded it from fifty acres to 150 acres. Business correspondence indicates the Massengills had positive relationships with other growers throughout the United States. One gladiola corm supplier in Upper Montclair, New Jersey even offered to quote the Massengills discounted pricing on unique varieties. The Massengills were also active in the Delray Beach community, supplying local churches with free flowers once a week. The couple retired in 1976, but memories of their farm and flowers remain in Delray Beach. Another grower, Mike Machek, Jr., moved to Delray Beach in 1941 with his wife, Helen, and their children. In a 2006 interview, Machek noted he was known for two things throughout Delray: his gladioli and being a Scout leader. The Macheks were instrumental in the continued celebration of local agriculture through the creation of the Gladioli Festival and Fair.

The Gladioli Festival and Fair

While the Gladioli Festival was originally meant to be a small-town flower exhibition with a few concessions, the event quickly blossomed into an annual phenomenon dubbed “The Mardi Gras of Flowers.” From 1947 to 1953, the festival welcomed Hollywood stars like Vera-Ellen – best known for her roles in On the Town (1949) and White Christmas (1954) – to Atlantic Avenue. In addition to displays of gladioli, produce, and livestock, local builders brought miniature homes to showcase their projected developments. There were also exhibits by Delray Book Shop, Boats Unlimited, the United States Sugar Corporation of Clewiston, and the Palm Beach County Tuberculosis and Health Association. Businesses and clubs built lavish, flower-covered floats for the parade and organizers held regatta races on Lake Ida. Visitors enjoyed high-diving acts, a polo match at the Gulfstream Polo Club, and nightly prizes, including a deep-freezer, an automatic washing machine, a sink, and Samsonite luggage.

Although the festival formally ended in the 1950s, the spirit and memories of the Gladioli Festival remained at the forefront of community leaders’ minds. In 1962, a committee decided to expand the agricultural expo to include arts and crafts, highlighting local artisans and musicians. They also recognized the opportunity of scheduling the new festival for the first weekend after Easter by extending the tourist season. The festival became known as the Delray Affair, a celebration of local food, art, crafts, and local businesses. Now in its 61st year, the Delray Affair can easily trace its roots back to the spectacle and spirit of the Gladioli Festival and Delray’s agricultural heritage. As you enjoy the sights and sounds of Atlantic Avenue this weekend, and savor Delray-grown produce year-round, consider thanking a farmer (or a farming ancestor)! To learn more, be sure to stop by the Delray Beach Historical Society’s campus to view our Gladioli exhibit, purchase gladioli corms, and immerse yourself in our town’s agricultural past, present, and future.

Email the Archivist for questions or comments! [email protected]