By Kayleigh Howald

Every Floridian – whether a seasoned veteran of the Sunshine State or a new arrival – has a hurricane story. Maybe it is the story of their first hurricane: the rush of preparation, the long lines at gas stations, and the bare front porches as neighbors prepare their homes. Maybe it is a particularly joyful hurricane party when the 5:00pm track moved further east, and the crowd erupted into cheers. Maybe it is the birth of a child or grandchild as the barometric pressure dropped. Maybe it is sounds of driving rains and whistling winds, or the eerie silence as the eye passed overhead. As we approach the peak of Atlantic hurricane season in September, it seemed like an appropriate time to explore some of the storms that impacted Delray Beach and to reflect on our local stories.

In this first installment, we will focus on Delray Beach’s early hurricanes in the first half of the 20th century. In a time before television news or even extensive radio broadcasting, Florida’s residents measured the approaching storm using barometers and newspaper reports. The stories that emerge from these hurricanes are ones of support, growth, devastation, and death. There are also stories of perseverance and the ability to rebuild homes and communities in the face of unfathomable tragedy.

What Exactly is a Hurricane?

Hurricanes are rotating weather systems with sustained winds of at least 74 mph. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), there are four main ingredients necessary for a hurricane. First, a pre-existing weather disturbance forms, such as a tropical wave or storm. Then, the weather disturbance must encounter warm water measuring at least 80 degrees Fahrenheit, with a depth of 150 feet. As the disturbance moves over the ocean or gulf, the warm, humid air rises underneath the low-pressure wave and quickly cools in the clouds to create thunderstorm activity, the third ingredient. The warmer the water, the more fuel for the storm. The final ingredient is low wind shear, which allows the hurricane to strengthen and maintain an organized rotation. While hurricanes are measured by their maximum sustained wind speed, known as the Saffir-Simpson Scale, other deadly hazards very often accompany hurricanes, such as wind gusts, rainfall flooding, tornadoes, and storm surge.

1903 – SS Inchulva

On September 11, 1903, a strong hurricane brought damaging winds to South Florida. The Tropical Sun, a local newspaper published in Juno and West Palm Beach, reported that there were “half a dozen vessels ashore between Palm Beach and Fort Lauderdale.” Businesses were damaged in West Palm Beach, while the grounds of the Royal Poinciana Hotel were “torn and upheaved.” Two steamers wrecked in the storm in Delray, most notably the British merchant ship, S.S. Inchulva. The steamship grounded approximately 150 yards off Delray’s coastline and was quickly torn apart by the waves after Captain G.W. Davis lowered both anchors. Of the crew members, approximately 19 survived, including the captain, first mate, second mate, steward, fireman, cook, and carpenter.

By noon on September 12, the survivors of the Inchulva reached the shore on a raft, and took refuge at the Chapman House, or “Grand Hotel,” the largest hotel in Delray at the time. Under the care of Lucy Chapman, they (and several other Delray residents who sheltered in the hotel) received hot food, dry clothing, and “every kindness and attention at the hands of Mrs. Chapman.” The nine crew members who died in the storm were buried on the ridge overlooking the ocean. The Inchulva wreck site remains a popular diving spot and the five sections can be found scattered offshore. It is currently home to a variety of tropical fish and the occasional lobster.

1926 – Great Bahamas Hurricane (July) & Great Miami Hurricane (September)

While the Roaring ‘20s were in full swing in 1926, the Florida Land Boom bubble was beginning to burst, and the dual hurricanes of 1926 did not alleviate matters. The first storm – the Great Bahamas Hurricane – occurred in late July and battered Delray Beach for 18 hours, according to one newspaper report. The winds leveled homes and barns and destroyed numerous commercial properties. The news account described how electrical poles snapped, leaving the town shrouded in darkness, and shattered plate glass windows in homes and storefronts. One injured resident, R.H. Anderson, suffered a fractured skull and a back fracture when a tree fell on him. Since there was no local hospital, Anderson received medical treatment at Edwards Hospital in Ft. Lauderdale.

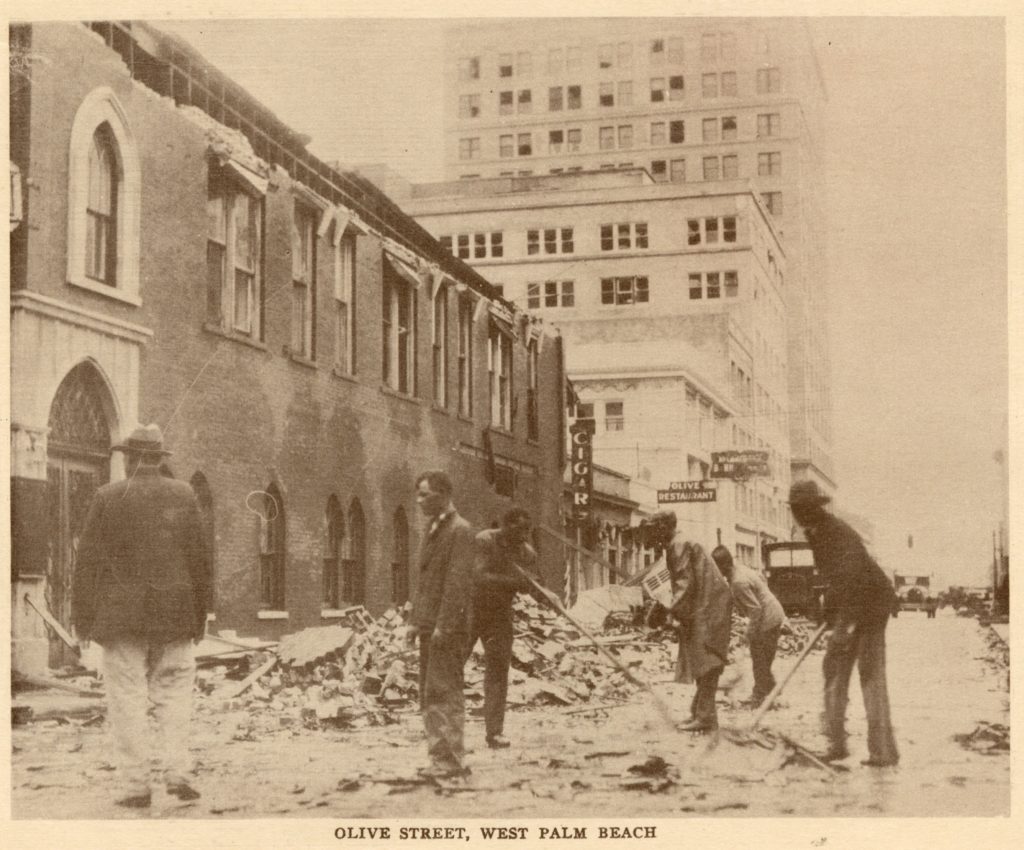

Just a few short months later, on September 18, another hurricane made landfall near Miami, Cocoanut Grove, and South Miami, with the eye passing over the downtown area. Many of Miami’s residents – new transplants, who had never experienced hurricanes – assumed the storm was over. 35 minutes later, however, the crowded streets were bombarded by the stronger side of the storm, with sustained winds of 128 mph and a ten-foot storm surge that flooded Miami Beach and the barrier islands. From Miami to Fort Lauderdale, nearly 50,000 people were left homeless, with a reported 854 hospitalized and 113 dead from the storm (the final death toll of the Miami hurricane was 243, including in Pensacola and Mobile, Alabama).

While it caused additional damage in Delray Beach and other towns throughout South Florida, the damage to the economy and land development was extensive. Promoters attempted to counter the media reports of razed cities by developing a temporary radio station to broadcast a softened version of national headlines. The widespread destruction, however, led to a significant dip in property prices across South Florida. It also showed weaknesses in Lake Okeechobee’s levees (where flooding caused 386 deaths) and the fragility of Florida’s structures, a mere hint of what was to come…

1928 – Okeechobee Hurricane

Two years later, South Florida was dealt another devastating blow in the form of a 150-mph storm known as the San Felipe Segundo-Okeechobee Hurricane. The hurricane developed near the Cape Verde Islands on September 10, 1928, and intensified as it traveled westward across the Atlantic, making landfall in Guadeloupe as a major hurricane. The storm strengthened and struck Puerto Rico with 160-mph winds – what we would now consider a Category 5 hurricane. In Puerto Rico, over 300 people died, and hundreds of thousands were left homeless and destitute following the storm’s destruction of homes and crops.

When the hurricane reached Florida on September 16, it made landfall in Palm Beach County, and the eyewall caused considerable damage to coastal Jupiter as it moved over South Florida. Winds and rain brought overwhelming property damaging along the coastline as far south as Pompano. In Delray Beach, the storm flattened houses and shifted buildings on their foundations. Delray Motor Co., the Cathcart Building, and Delray Laundry were left in ruins, as seen in the pictures below. According to the Delray Beach News, the “damage to buildings in Delray Beach and the immediate back country” totaled $1,029,100 (approximately $18 million today). 350 families lost their homes in the Delray Beach area, as nearly a quarter of the homes were destroyed. Four people died in the storm, eight suffered serious injuries, and eight people were hospitalized.

In the Glades, however, the storm proved catastrophically devastating. After the 1926 hurricanes, state officials were well-aware of how ineffective the dikes were as major flooding had occurred in Moore Haven, a town on the southwestern side of Lake Okeechobee. According to historian Eric Jay Dolin, representatives from the Glades urged the state legislature to fund improvements to the dike system, but the state had fallen into a deep recession after 1926. “As the memories of the 1926 hurricane faded,” Dolin explained, “the urgency of the project receded as well. But Lake Okeechobee remained a ticking time bomb, and on the evening of September 16, 1928, it exploded.”

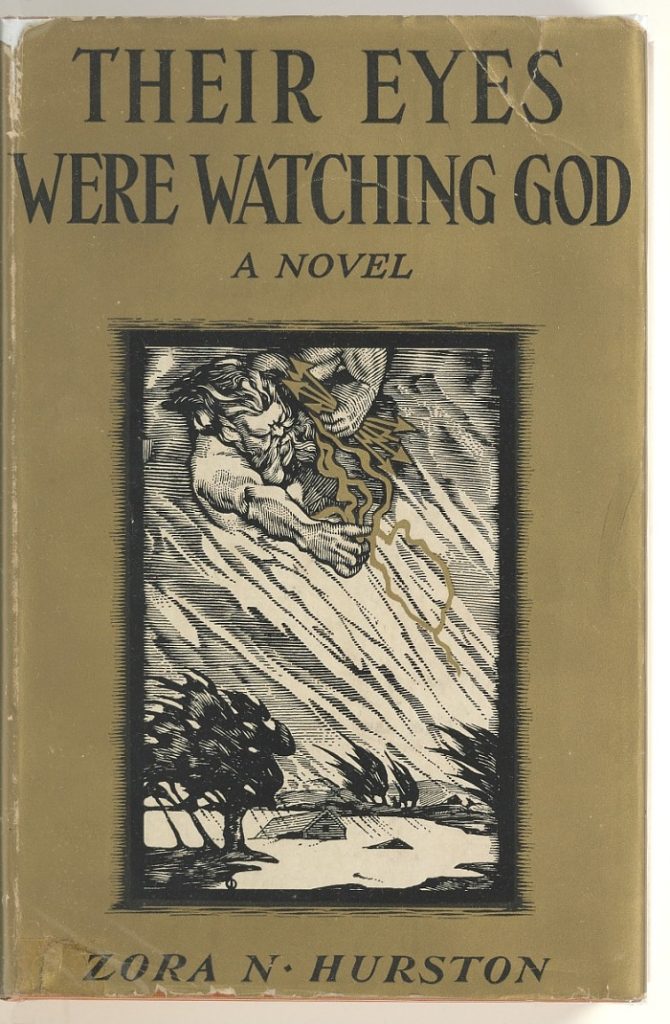

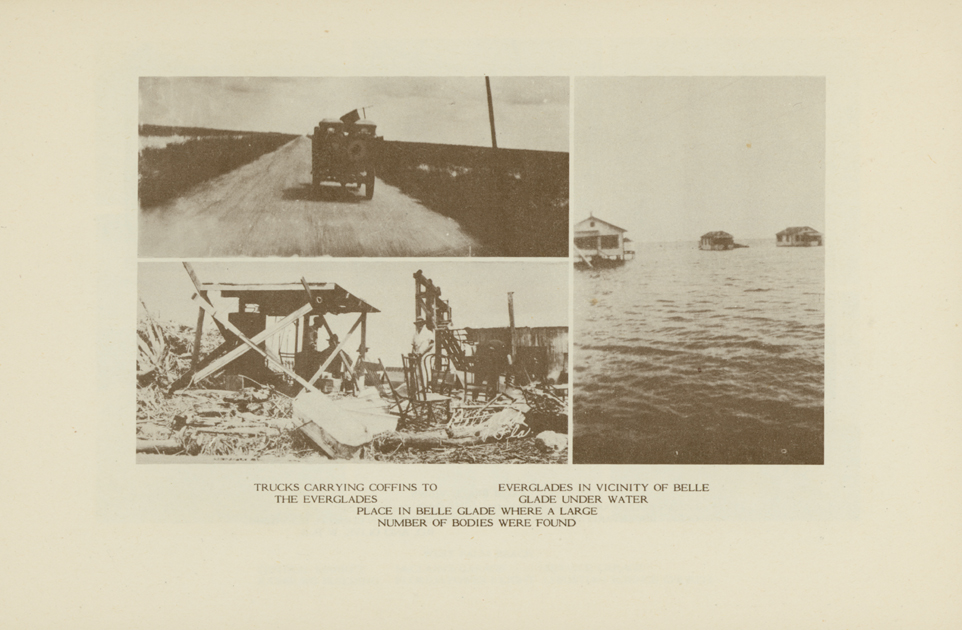

As the hurricane began to turn north near Lake Okeechobee, the storm surge that flooded the coastline also occurred along the south shore of Lake Okeechobee where the surge quickly washed over the five to eight-foot dikes and flooded the neighboring towns of Belle Glade, Pahokee, Canal Point, Chosen, and South Bay. According to the University of Rhode Island, the water in Belle Glade rose seven feet at a rate of one inch per minute. Approximately 2,000 people in the Glades – mostly non-white migrant farm workers – drowned in the floodwaters, making it the second deadliest hurricane in United States history after the 1900 Galveston Hurricane. In 2003, the National Hurricane Center updated the official death toll to “at least 2,500,” noting that the exact number will never be known as many victims were swept into the Everglades and never recovered.

The treatment of both victims and survivors after the storm reflected an ongoing tragedy in the 1920s: the ubiquity of Jim Crow in South Florida. While volunteers traveled to the Glades to pull victims from the flooded soil, Black survivors were often conscripted at gunpoint to recover the bodies of both humans and animals killed in the storm. Most of the bodies were burned or buried in makeshift mass graves around the lake. At least 1,600 people were buried at Port Mayaca, ultimately forming the Port Mayaca Memorial Gardens cemetery. Another 743 victims were brought to West Palm Beach via barge, trucks, and horse-drawn carts and buried in two separate areas of the city. Officials secured wooden caskets for 69 white victims, who were buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in downtown West Palm Beach. 674 Black men, women, and children, however, were placed in a mass grave in the pauper’s cemetery on Tamarind Avenue and 25th Street. Although memorial rites were conducted at both locations on September 30, 1928 – where activist and educator Mary McLeod Bethune presided over the ceremony on Tamarind – their final resting place was left unmarked and forgotten until 1991. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, the land was sold numerous times for private industrial use (including as a slaughterhouse and sewage treatment plant), then finally purchased by West Palm Beach in 2000. A historical marker was erected in 2008 on the 80th anniversary of the storm.

In 1932, the Army Corps of Engineers began construction on an earthen dike around Lake Okeechobee. The first dike was completed in 1938 and was 85 miles long, 34 to 38 feet high, and up to 150 feet wide at the base. Several drainage canals, hurricane gates, and locks were built to control the water, and construction continued until the dike encompassed almost the entire lake. In 1960, it was renamed the Hebert Hoover Dike.

1947 – Fort Lauderdale Hurricane

By 1947, Delray Beach had been spared from many of the major hurricanes of the 1930s and early 1940s. Businesses, hotels, and restaurants were preparing for a busy season, as were residents and workers in Gulf Stream, despite the seemingly endless rains. In 1947, Florida received an average of 72 inches of rain, almost 20 inches higher than the year before. When a large, slow-moving storm hit Fort Lauderdale on September 17, it brought even more water to saturated South Florida.

Although the hurricane made landfall at Fort Lauderdale, hurricane force winds were experienced along Florida’s east coast from Cape Canaveral to Key Largo. 100 mph or higher winds were felt from Miami to West Palm Beach. The highest sustained winds were 121 and the Hillsboro Lighthouse measured 155 mph gusts. It was one of the largest storms up to that point, and it battered the east coast for over 15 hours.

The Fort Lauderdale Hurricane of 1947 caused extensive damage throughout Delray Beach, as the northern eye wall passed over Palm Beach County. Large stretches of A1A were washed away. During the storm, 200 residents gathered in the Bon Aire Hotel, a Mediterranean Revival style hotel that served as an emergency Red Cross shelter. They reportedly huddled together in the lobby and under stairwells. While Buster Musgraves, then manager of the hotel, boarded up the downstairs plate glass windows of the shops and lobby, the upstairs windows were unprotected. Gravel from the roof and other debris broke several windows and caused significant water damage.

In Briny Breezes and Gulf Stream, many homes were also damaged or destroyed. The Delray Beach News reported that J.D.S. Coleman’s estate was “unroofed and glass blown from the windows,” and the terrace of the Whitney estate was “gone.” One room of the Iglehart home was crushed by the waves and a row of pines south of Benson’s dairy were uprooted.

One of the most well-known images is of the Miller house, a grand Mediterranean Revival home that was being rented by Mr. and Mrs. Edward Bowman. The Bowmans were sheltering with another couple, Mr. and Mrs. Vincent J. Jordan, near the Pines by the Sea cottages, which were managed by Jordan and owned by Henry H. Metcalf. During the storm, the roof of the main house began to rise and lower with the gusts of wind. The couples quickly escaped, just as the house collapsed and it washed into the ocean. The Bowmans and Jordans formed a chain and, arm-in-arm, waded through waist-deep water to the Anson Graves house, located only 500 to 600 feet back from the beach. While all four survived, most of their belongings did not.

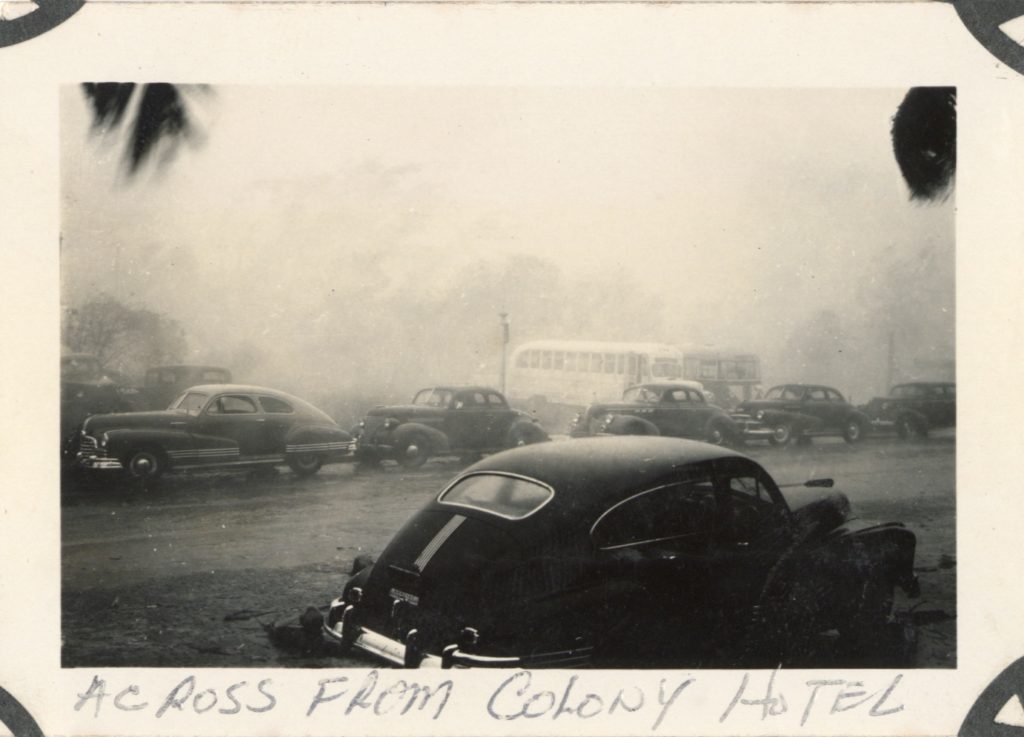

Unlike previous storms, there were no deaths reported from the storm. In fact, Delray “gained one potential citizen during the disastrous hurricane.” According to the Delray Beach News, “A five-pound baby girl was born to Mrs. Robert Kiewich who had taken shelter at the Colony Hotel. The baby was named Merry Gale.”

Following the storm, power outages impacted the city water pumps and much of Delray Beach was left without water for several days. Another hurricane in October 1947 added to the substantial flooding and hampered rebuilding efforts. West Palm Beach, for example, received 4.75 inches of rain on September 17, 14.49 inches for the rest of September, and another 14.68 inches in October! These rainfall totals are reflected in many photographs from our archives, as images marked October 1947 show significant street flooding throughout Delray Beach.

Looking Ahead: Climate Change and Hurricanes

As these stories indicate, we have a rich history of hurricanes in our area, including major storms with winds reaching over 110 mph. Each year, however, it becomes more and more difficult to point to just one strong storm in a season, or one calamitous natural event. While hurricanes and tropical storms are not necessarily more frequent (nor their strength unprecedented), a greater proportion of the storms that form each year reach higher, more intense levels.

According to NASA, climate change significantly impacts the intensity, rainfall, storm surge, and speed of hurricanes. As the earth warms and sea levels rise, flooding from increased rain and higher storm surge can lead to disastrous flooding for both coastal and inland areas. Though continuous improvements are made to the levee system around Lake Okeechobee, the dikes, locks, and other mechanisms have not been tested in a Category 4 or 5 storm.

Models also show that warming ocean temperatures and additional moisture in the air bring an increase in hurricane wind intensity, as the two factors help fuel hurricanes. As we look ahead to the future, it is important to remember stories like the ones above and think about how we may begin to prepare for catastrophic winds, flooding, or both.

Stay tuned for the second part of our exploration of Delray Beach’s hurricane history. We will cover the late 20th century and 21st century, including Hurricanes Cleo, Irene, Frances, Jeanne, Wilma, Irma, and Dorian. We will also delve into the history of hurricane naming and the woman who challenged the National Weather Service!

For questions or comments, email the Archivist! [email protected]