By Kayleigh Howald

While Catherine E. Strong’s name is familiar to many throughout the Delray Beach area, her story and contributions to Delray Beach and south Palm Beach County may be less well-known. Archival records and newspapers illustrate Strong’s steadfastness in support of the entire Delray Beach community. This Women’s History Month, we celebrate the work and achievements of Delray Beach’s first woman mayor, Catherine Strong.

Her Early Years: 1911-1950

Catherine Elizabeth Link Strong was born in New York on February 16, 1911 to Frederick and Catherine Link. The family relocated to Delray Beach in approximately 1922 and her father, Frederick, worked briefly as a craftsman for Mizner Industries. He then became a structural engineer for the Del-Ida Park subdivision. In 1929, Catherine married Samuel F. Stanton, a World War I veteran, and moved to West Palm Beach. Their son Herbert, named after her brother, was born in approximately 1931. The couple divorced in 1934. In 1939, she married Milton “Jack” Strong, a roofing contractor. Strong, born in 1905, came to Florida from Spokane, Washington in 1925. He was a member of the Chamber of Commerce and the Florida Roofing Association.

Strong was involved in the Delray Beach community from a young age. When she was a teenager, she played trombone in the Women’s Business Band. After marrying Jack Strong, she became co-owner of Tropical Roofing and worked in real estate. She became a leading member of the Chamber of Commerce, and actively involved in many of their events, tours, and efforts to support Delray Beach businesses. She was also a member of the American Legion Auxiliary, the Lions’ Auxiliary, and the Evening Garden Club.

She was also, perhaps unsurprisingly, interested in politics and municipal government. In 1936, she joined the Palm Beach County Women’s Democratic Club and was elected secretary. Between 1940 and 1946, Strong worked as Delray Beach city clerk, tax collector, and clerk of the court. During this time, she became an integral part of Delray Beach residents’ lives as they paid bills and ran for elected office.

In 1950, she became the first woman to have her name drawn and called for jury duty in Palm Beach County. “I’m just so thrilled,” she told the Palm Beach Post. “I think it’s an honor and a privilege.” Strong’s name was one of only 40 women included on the 2,811-name jury list.

Mayor Catherine E. Strong

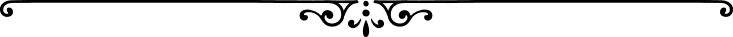

In 1953, Strong became one of ten candidates vying for four seats on the City Council. Other candidates included Robert J. Holland, W.C. Allen, W.A. Jacobs, Roland Joyal, Dr. J. R. Nider, R.O. Priest, Fred Sellers, Glenn Sundy, and Dr. W.C. Williams. Strong received 902 votes during the primary: the most votes ever received by a single candidate in Delray’s municipal elections. In the general election, she won 1,188 votes. She joined W. C. Allen, Glenn Sundy, Robert “Bob” Holland, and Alma K. Woehle, Delray’s first councilwoman, in city leadership.

As Strong received the most votes, the council selected her as mayor. The Miami Herald reported her win under the headline, “A Woman Wields the Mayor’s Gavel,” and stated, “Thus Mrs. Strong has been given an opportunity to demonstrate in her community a fact which is winning increasing acceptance – that qualified women can do a good job in responsible posts of government.”

During her time in office, Strong immediately worked to provide support to the Delray Beach community. She worked to update and maintain municipal cemetery records; worked with the Palm Beach County Resources Development Board to bring industrial jobs to Delray Beach; organized the paving and repair of 22 downtown blocks; and partnered with neighboring Boynton Beach and Boca Raton to obtain additional beachfront. She was also a member of the Carver High School Scholarship and Loan Fund committee, which provided some tuition coverage for four Carver High School seniors each year. She also became a local chairperson for progressive gubernatorial candidate J. Brailey Odham.

“The Growth of Our Community”

After her term as mayor, Strong continued to be a vocal and involved member of the city commission from 1955 to 1957. When she ran for a second two-year term, she stated, “When I took office in 1954, I had hoped that, in two years, we could achieve certain goals, make needed improvements at city hall and set in motion projects vital to the growth of our community. A start has been made, but much remains to be done.”

In 1956, she voted against a bulkhead for the Seagate Beach Club, then owned by major developer Arthur Vining Davis, for fear it would cause extreme erosion during high tides or a hurricane. In 1957, she co-chaired the city landscaping committee with Addie Sundy. The committee raised funds to build a fountain in the municipal cemetery, as well as a walkway, hibiscus trees, and memorial palm trees. In 1965, the Evening Garden Club donated the fountain in Strong’s memory.

A Commissioner for All of Delray Beach

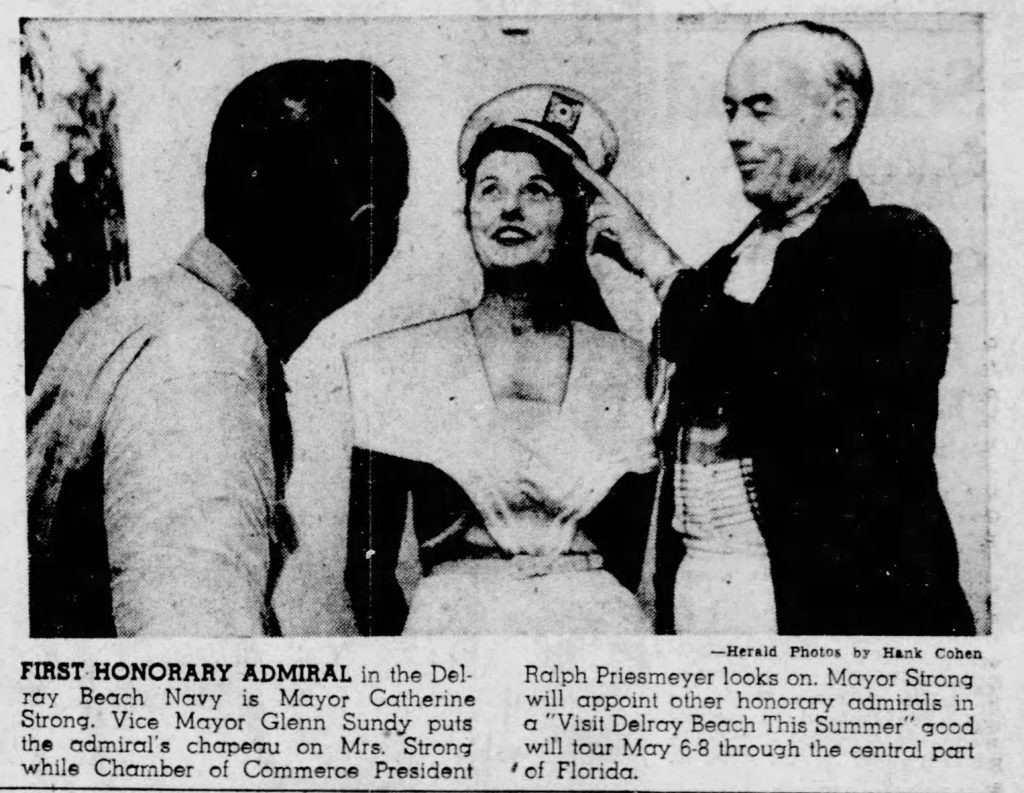

In 1956, Strong became heavily involved in a major civil rights moment in Delray Beach: the desegregation of Delray’s municipal beach. Strong was named in a federal lawsuit filed by NAACP attorney Francisco A. Rodriguez Jr. against Mayor W.J. Snow and the Delray Beach City Commission. According to the suit, Delray Beach’s Black residents, “solely because of their race and ancestry” were denied access to the beach and pool. This refusal violated the Equal Protection of Laws guaranteed by both the federal and state constitutions.

On May 16, 1956, during a hearing for the federal suit against the city, Strong testified there were no ordinances banning people of color from the municipal beach and pool. Federal Judge Emmett C. Choate dismissed the case. For many, this signified a victory: an expressed, official policy that the beach was open to everyone. When Delray’s Black citizens exercised their right to access the beach, however, a group of angry white citizens attacked the group and threatened violence. Residents threatened commissioners and a group of young men burned a large cross in front of the Ace High Club, located on West Atlantic Avenue.

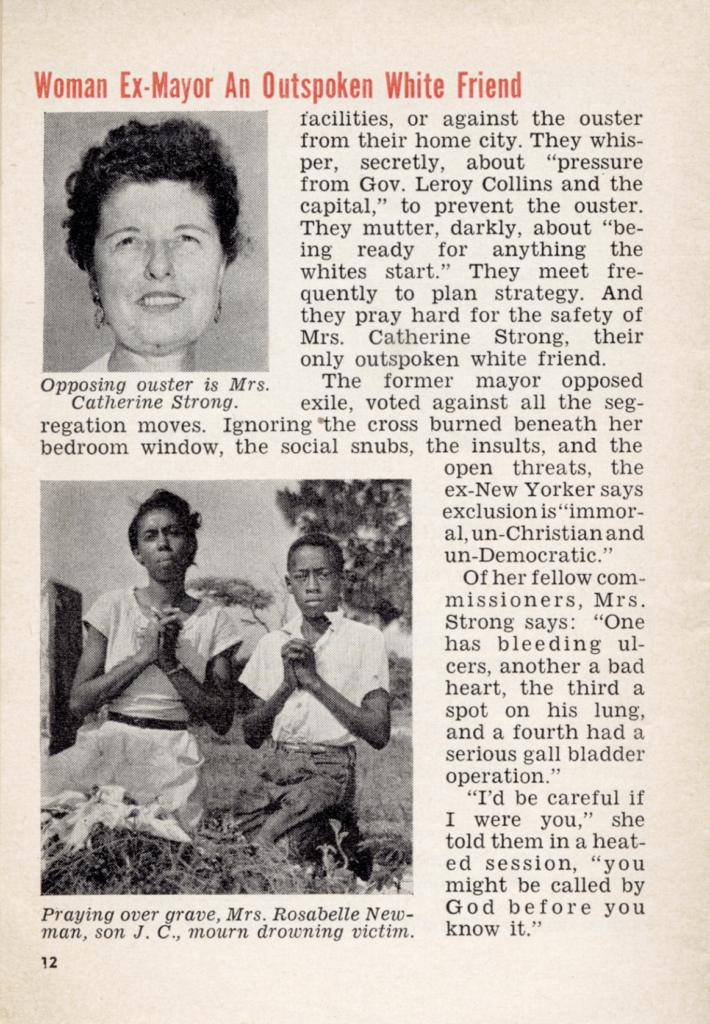

Civic leadership passed several “emergency ordinances” to curb racial violence, but these laws often disproportionally harmed Delray’s Black community. This included an outright ban of African Americans on the beach and municipal pool, police searches, and roadblocks. Catherine Strong was the only commissioner to vote against the ordinances, pushing back against her fellow leaders each time. When the commission voted to exclude the entire Black district from Delray Beach’s city limits, Strong emphatically voted no and did not sign the resolution. “I don’t think this is going to solve the problem,” she stated. “The public hasn’t had a chance to express itself on this exclusion and I don’t care for this manner of cramming it through.”

On June 7, 1956, Strong wrote a letter to Governor LeRoy Collins, asking him to veto the resolution. She wrote: “My fellow commissioners admitted they were only doing it to show the Negroes quote, ‘Who’s boss.’ In a problem so explosive, we cannot afford emotionalism on the official level… I have written at such length to attempt, Governor, to fill you in on the background to this latest action. I can tell you in all sincerity that the Commission majority did not act with the support of a majority of our citizens in voting to kick the Negro areas out of Delray Beach. They didn’t even consider such problems that would be created as sanitation, fire and police protection, and garbage collection that would be brought on by having an unincorporated area right in the heart of our city.”

According to the June 28, 1956 issue of Jet magazine, Strong allegedly faced social snubs, insults, open threats, and a “cross burned beneath her bedroom window.” Though Strong denied these claims, the Miami Herald later reported Strong was, in fact, “banned from some civic organizations for her racial stand,” but was “invited to rejoin two of them.”

After meeting with the Delray Beach Civic League and a televised commission meeting, the city finally agreed to drop the exclusion resolution and pledged to build a segregated swimming pool. In November 1956, the pool and park, located on NW 10th Avenue, was rededicated as the Teen Town Park. The park was renamed C. Spencer Pompey Park by 1976. Strong shared the ribbon-cutting ceremony with Frances J. Bright, the founder of the Negro Woman’s Club and one of Delray’s very first teachers.

Strong was not in favor of full integration in 1956. Like Governor Collins, she often worked to “maintain segregation by lawful means.” By the time she left the city commission, however, it seems that Strong’s opinions changed. In 1957, she joined Bob Holland, George McKay, Joe Baldwin Jr., and W.J. Snow on the city’s beach committee. The group recommended building a bathhouse, hiring a lifeguard and supervisor, and installing life ropes, benches, tables, and trash cans on the segregated beach in Ocean Ridge. In 1959, they urged the city to honor their pledge for at least 300-feet of coastline. In 1961, she was appointed to the Inter-Racial Committee with Leroy Baine, L. Brunner, R.J. Holland, John Paller, C. Spencer Pompey, John Van Sweden, Margaret Walsmith, L.L. Youngblood, and Ozie F. Youngblood.

Businesswoman and Hospital Founder

In addition to serving on city-appointed committees, Strong supported the wider South Florida community. In 1955, she joined the Gulfstream Hospital Association, the founding board of Bethesda Memorial Hospital. She was also appointed by Governor Collins to serve as the Secretary-Treasurer of the Board of Commissioners of the Southeastern Palm Beach County Hospital District. When Bethesda opened in 1959, it became the first hospital in southern Palm Beach County. It was also the first healthcare facility opened to all patients.

She even rescued animals! Along with Addie Sundy, the women fed and rescued dozens of cats and kittens along Railroad Avenue outside their neighboring businesses: Tropical Roofing Co. and Sundy Feed & Fertilizer Co.

Her Legacy: 1963-present

On December 23, 1963, after what was described as a “brief illness,” Catherine Strong died at Bethesda Memorial Hospital. She was only 52-years-old. Strong left a lasting impact on Delray Beach and the surrounding communities. She was honored with a wing at Bethesda Memorial Hospital, a community center, the fountain at Delray Beach Memorial Gardens cemetery, and the Catherine Strong Splash Park. Strong’s name is synonymous throughout Delray Beach with dedication, persistence, daring, and kindness.

“This tall, lithesome, beautiful lady with an iron will, indomitable courage and compassionate sensitivity,” C. Spencer Pompey said of Strong, “became the shining symbol of love, charity, understanding and forgiveness and, indeed, hope for an entire community.”

To learn more about Delray Beach’s many trailblazing women, please contact the Archivist at [email protected].

To learn more about Delray’s civil rights history, including the beach integration movement and Florida women’s liberation, please visit our exhibit: The Land of Sunshine and Dreams: Delray Beach in the 1950s & 1960s. Open Tuesday through Saturday, 11AM to 3PM.