By Tom Warnke

Delray’s beach was a vital asset from the settlement’s inception. In 1895, pioneers Sarah Gleason and William H. Hunt, her husband’s business partner, sold their beachfront land to William S. Linton. When Linton later defaulted on his loans, the property reverted to Gleason, as well as Hunt’s heirs: Belle G. Dimick Reese and Ella Dimick Potter. In 1899, the three visionary women gave their two miles of oceanfront property to the residents of Delray for them to enjoy in perpetuity.

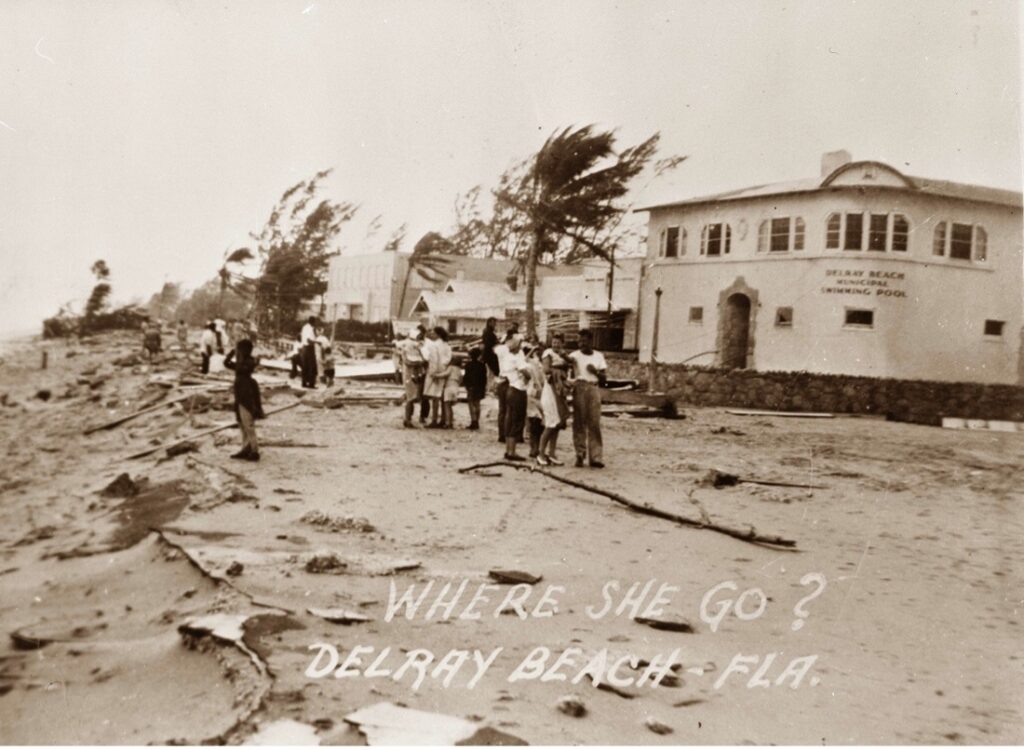

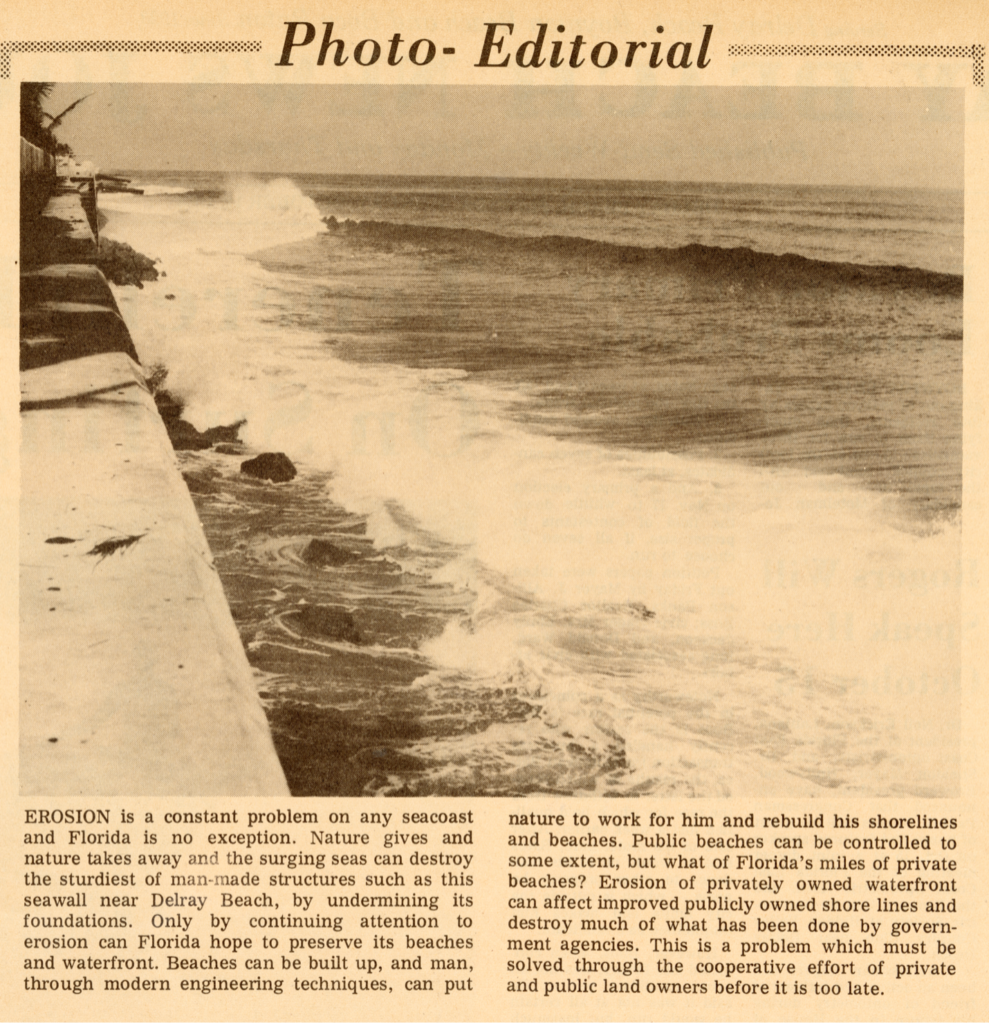

The beach quickly became a focal point for the town as a place of business and recreation. Shortly after the opening of the Boynton Inlet in 1927, however, Delray’s beach began to wash away. By the 1960s, it was critically eroded.

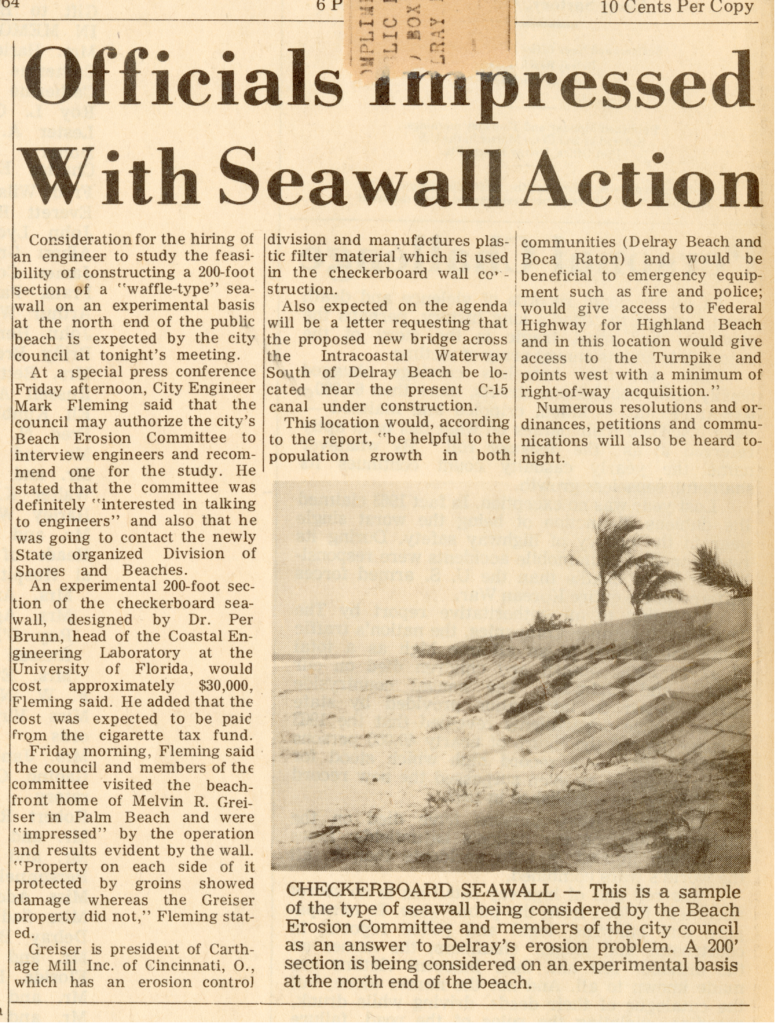

In the late 1960s, Delray Beach installed a concrete “revetment,” or retaining wall, attempting to save highway A1A from being destroyed by ocean waves. This ill-fated solution was constructed just as Delray’s residents voted to support a new technology: dredging material from offshore to replace its beach. This story has a happy ending, but it took many years to get there, and the concrete revetment experiment is but part of the story.

Storms and Beach Erosion

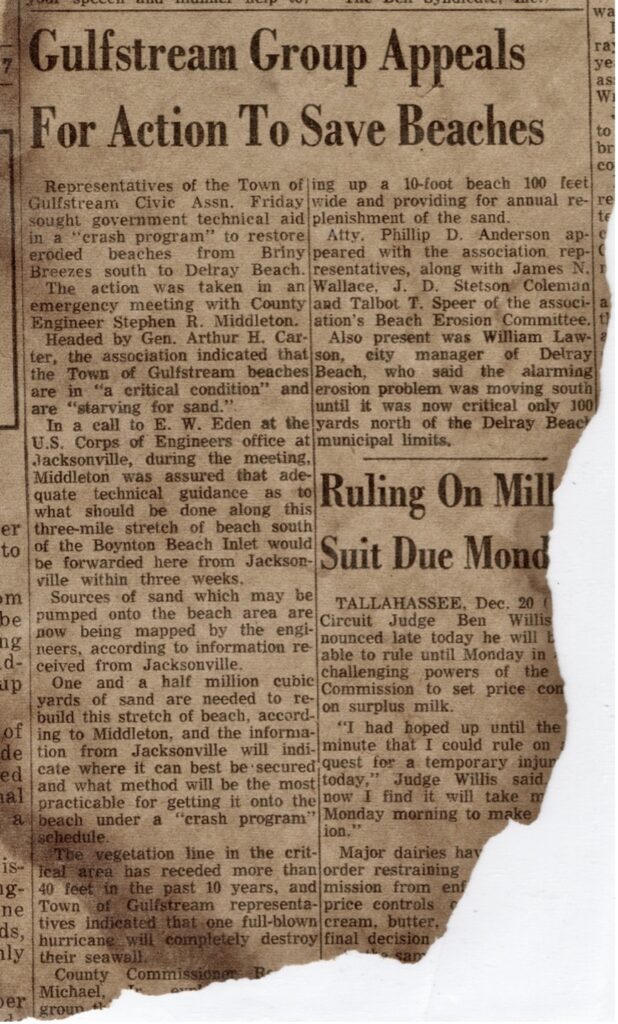

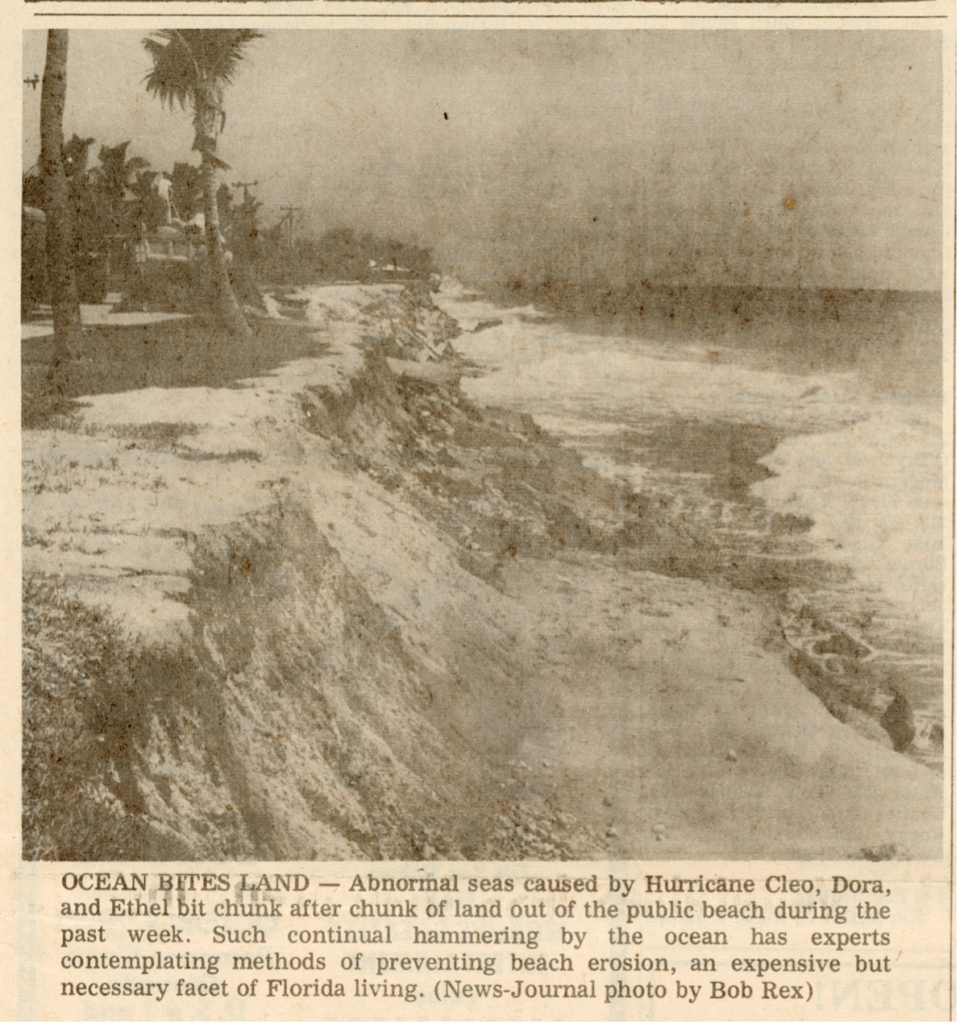

Summer hurricanes and winter Northeasters impacted the coastline at Delray Beach throughout its history, but beach erosion was not much of a problem until the late 1940s, when man-made structures were threatened. After the 1947 hurricane, Gulf Stream resident General Arthur H. Carter constructed a 20-foot thick seawall in front of the 1930 oceanfront home he had just purchased from Lila Vanderbilt Webb. In 1930, the beach in front of the Vanderbilt home stretched 200 feet to the ocean. Erosion caused by the construction of Boynton Inlet in 1927, along with hurricanes in 1947 and 1948 eroded many beaches in the Delray area and the Town of Gulf Stream appealed for state and federal help in 1957. In March 1962, the famous northeaster dubbed the “Ash Wednesday Storm” over-washed much of Delray’s highway A1A, causing significant damage. The waves from this storm are considered the largest ever to impact Delray Beach. In 1964, Hurricane Cleo caused more damage, followed by Hurricane Betsy in 1965, leaving Delray with very little beach.

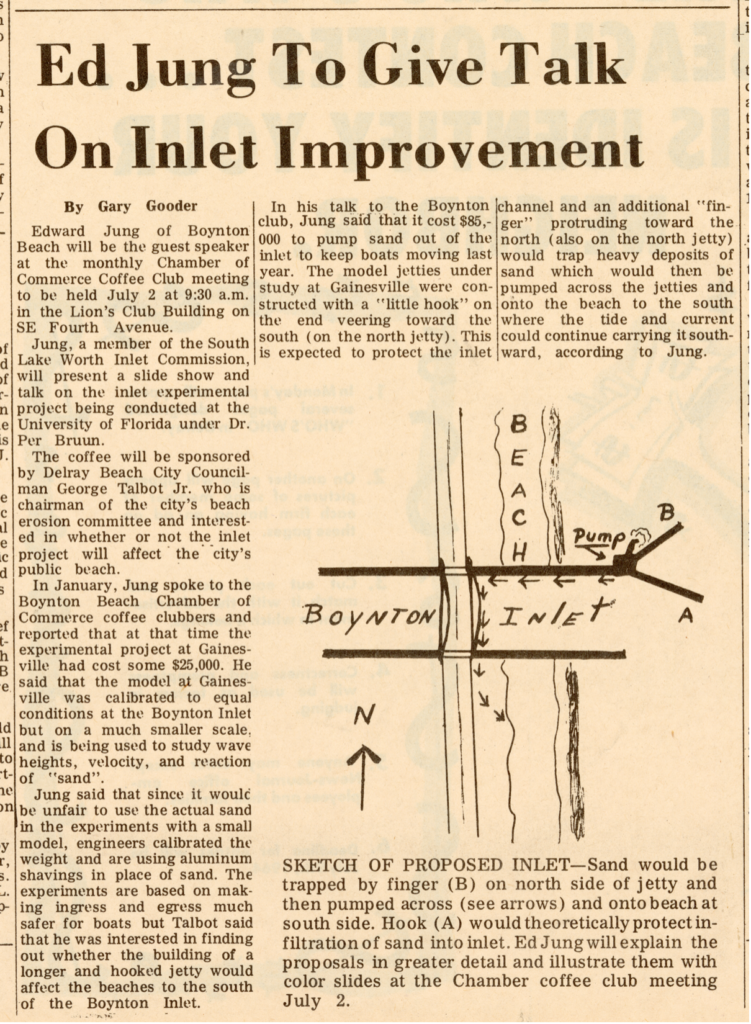

All during this time, the Boynton Inlet, five miles north, was robbing sand from Delray’s beaches by obstructing the normal southward flow of sand. In the late 1960s, Delray residents, including then-President of the Delray Beach Chamber of Commerce Roy Simon, witnessed the severe erosion problems. Simon, in particular, remembered the late 1940s when the state’s response to repeated erosion was to move highway A1A west, retreating from the threat. This relocation of A1A was done in Palm Beach, Manalapan, and Gulf Stream.

The normal amount of sand which travels to the south along Palm Beach County beaches averages 200,000 cubic yards per year. Consequently, sand that would normally move to the south was diverted by the inlet’s tidal flow, moving sand from the beach into the Lake Worth Lagoon, and also out to sea. Although a sand transfer plant was installed at the Inlet in 1937 to assist the normal “littoral drift” of sand to the south, it was only able to move a small portion of what was needed each year, continually starving beaches to the south, including Ocean Ridge, Gulf Stream, and Delray Beach.

The southward movement of sand on local beaches varies according to the year, with most wave energy coming from the northeast. This is due to the location of the Bahamas blocking most of the powerful waves from other directions. In the summertime, short-period waves cause northward migration of sand, but the amount is small in comparison. Also, the area of beach sand moved by wave action is limited to the ”zone of closure,” from the dune line to water about 25 feet deep. In this part of Florida, sand in water deeper than 25 feet rarely moves, even in the strongest storms.

Revetment: A Difficult Experiment

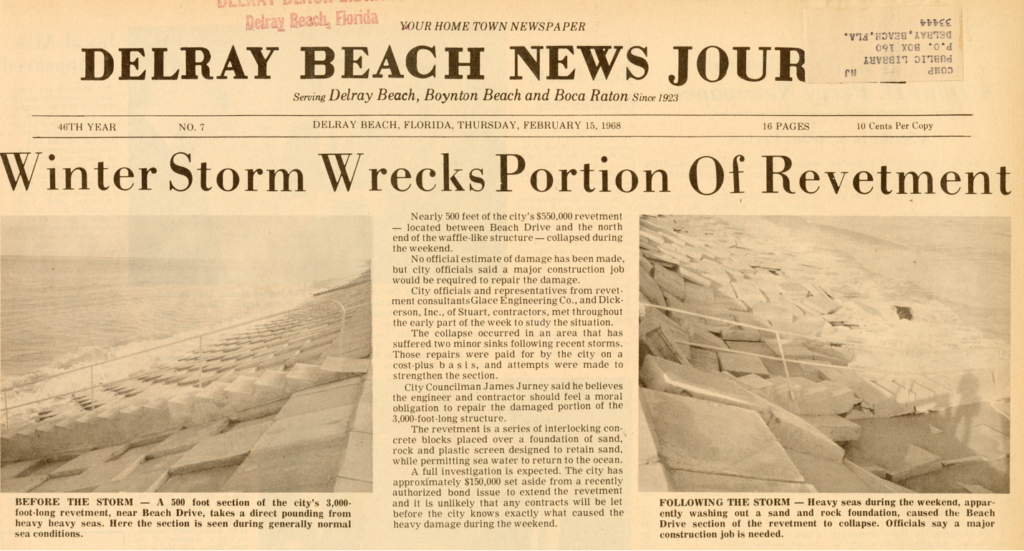

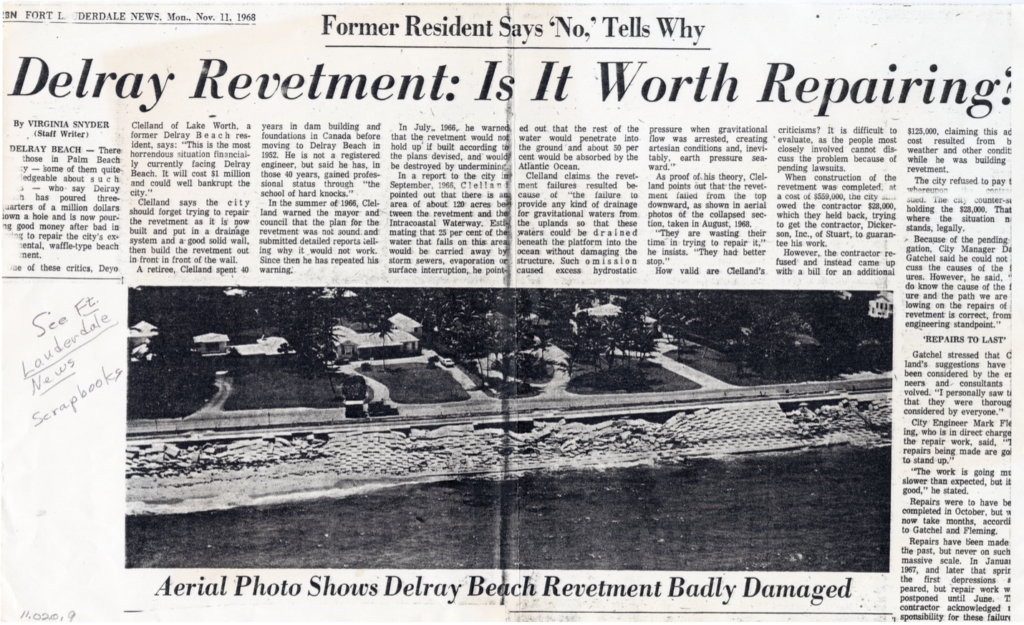

The failure of the concrete “revetment” in 1968 was predicted by Deyo Clelland, who warned the Delray Beach Commission repeatedly in 1966 that spending $550,000 for the project would be wasted. The Commission was impressed with a similar project in Hobe Sound, Florida, where an oceanfront homeowner constructed a sloped, interlocking concrete seawall which survived severe storms, saving his home. This type of revetment was referred to by the press as a sloping concrete “checkerboard” or “waffle” seawall. Clelland was an experienced civil engineer from New York who had constructed numerous dams. His contention was the project did not consider groundwater movement, which would undermine the project. Clelland further explained that half of local rainwater enters the shallow, surficial aquifer, slowly flowing to the ocean underground, and the revetment would create a virtual dam, undermining the project.

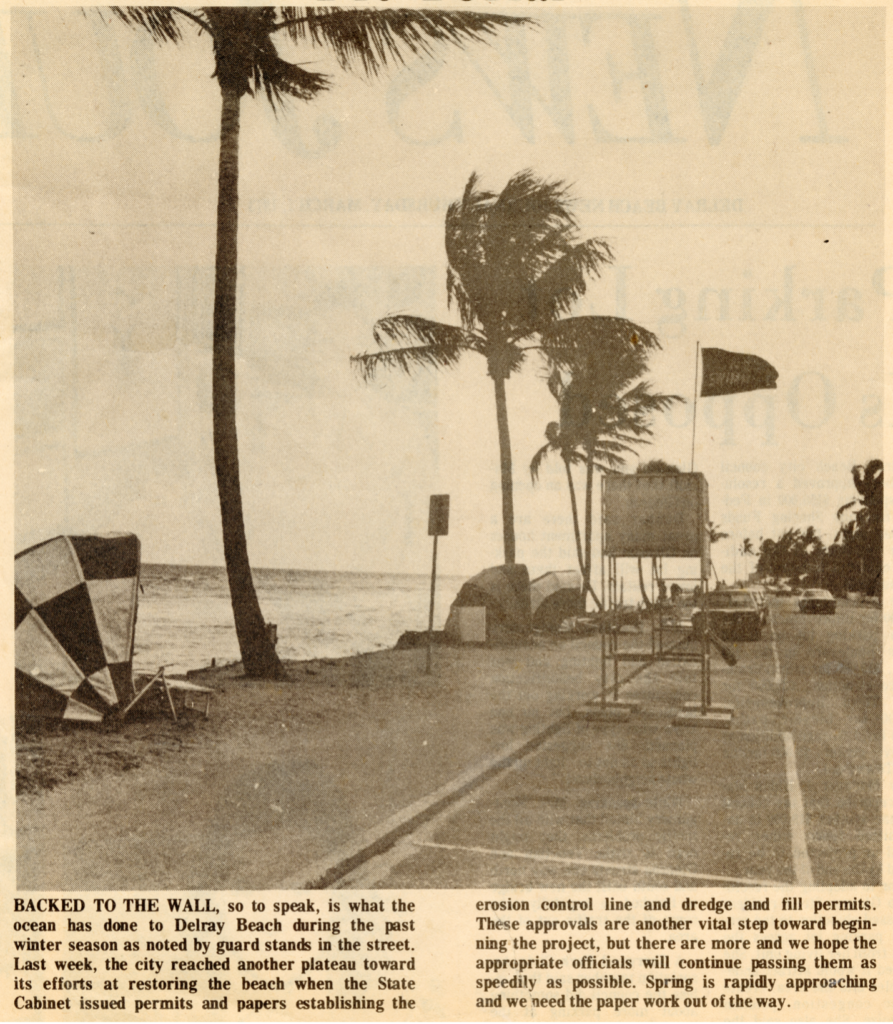

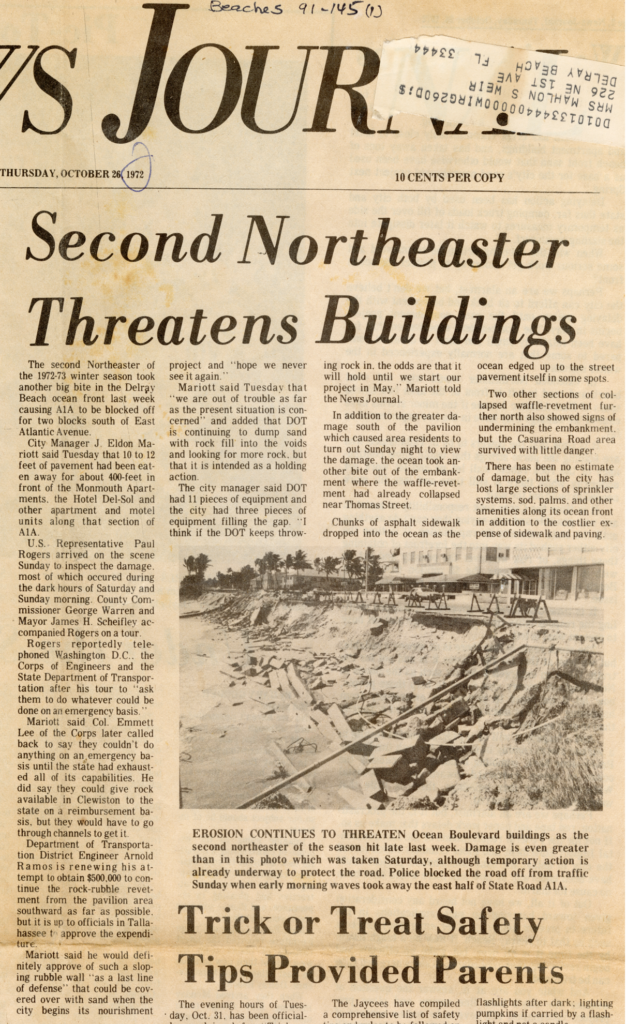

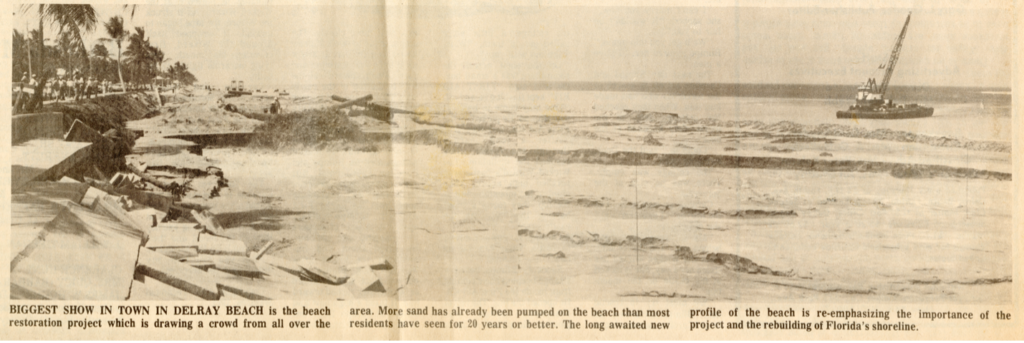

The Delray Beach Commission issued a contract to Stewart Contractors on April 21, 1966 to build the waffle-like concrete block revetment for $550,000. Work started on May 17 and the project was completed five months later, on November 1, 1966. On February 15, 1968, groundswells from a winter storm destroyed much of the revetment. The city blamed the contractor and the entire project had to be removed. At that point, the city decided to concentrate on dredging material from offshore to replenish 2.5 miles of beach.

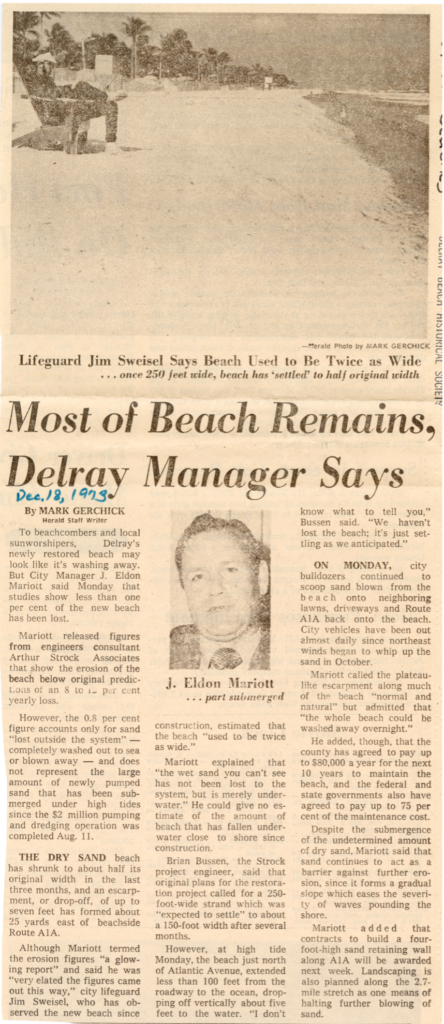

During the revetment debacle, local lifeguards criticized the failed efforts in the press. As a result, Delray’s City Manager David Gatchell issued a gag order on city staff, forbidding them to speak with the press. After her reporting on this issue, Fort Lauderdale News (now the Sun Sentinel) reporter Virginia Snyder was successful in having the gag order rescinded.

The Ganger Family Leads the Way

In 1969, Robert M. Ganger (1903-1992) purchased General Carter’s oceanfront home in Gulf Stream and encountered the erosion. He learned from General Carter’s widow that General Carter believed the erosion could be controlled by placing sand on the beach, a project he had been advocating long before he passed away in 1965. Thus began Robert M. Ganger’s ten-year effort to convince the government to employ what he believed was a simple solution: dredging material from offshore to replace the lost beach sand. Ganger was assisted by attorney Robert Chapin, and they maintained a comprehensive record of their efforts. Mr. Ganger’s records represent a starting point for what became the most successful erosion-control project of its kind in Florida history. Robert M. Ganger’s son, Robert W. Ganger, President of the Delray Beach Historical Society from 2006 until 2009, donated his father’s records to the Society in 2022.

In 1971, marine consulting firm Art Strock & Associates was commissioned by Ganger to prepare a study on sand replacement in Gulf Stream. The study determined the plan was feasible and the dredging would cost 1.2 million dollars. Ganger requested the state pay for half the cost. Gulf Stream Mayor William Koch, Jr. did not feel the Town residents would accept a beach fill project that would “open private beaches to the public and cost residents who did not own oceanfront property.” It was explained to the residents that the public already had rights to all oceanfront property below mean high water in Florida, but the Town still did not approve the erosion control plan.

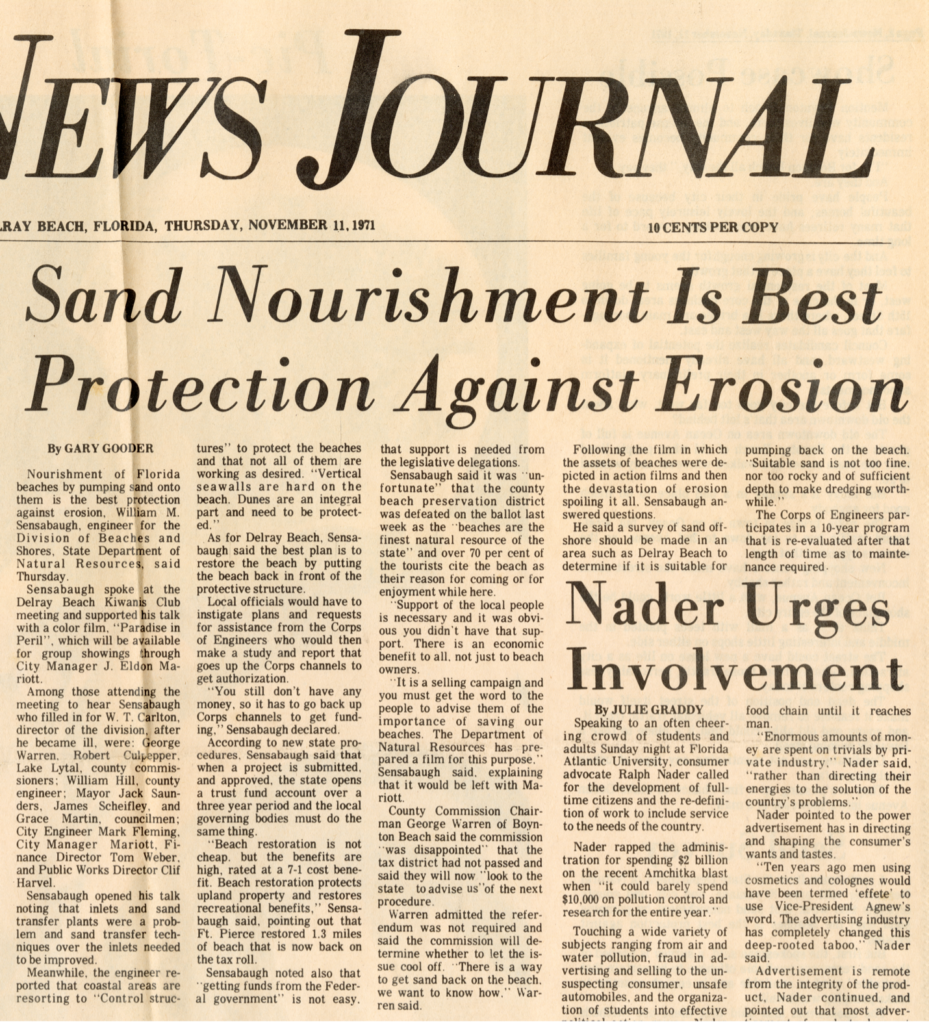

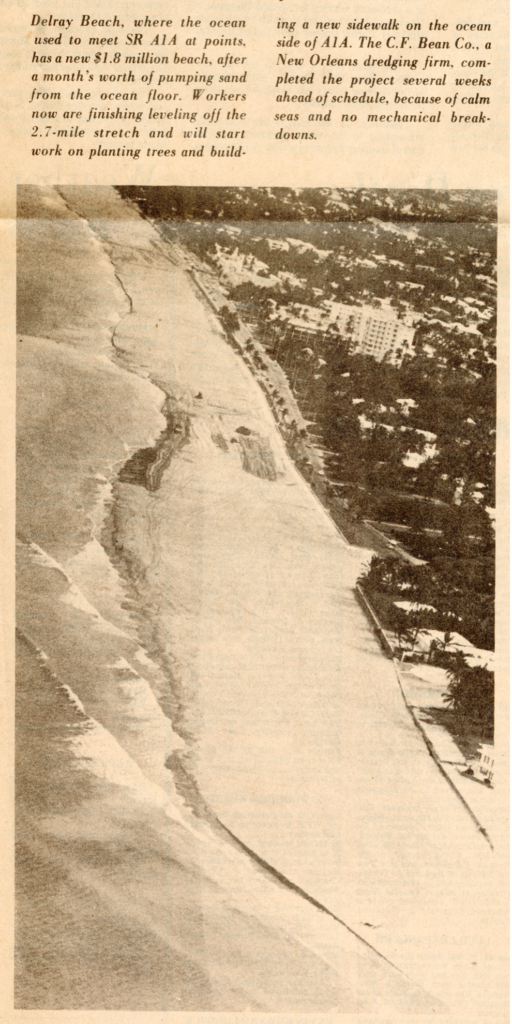

Delray Beach, however, adopted Ganger’s work for the larger Delray project and voters approved the city’s $2 million expenditure share in a 1972 bond referendum. The total cost was $10 million, with county, state and federal funds covering the $8 million balance. The total amount of dredged material was 1.4 million cubic yards and covered 2.5 miles of coastline. Planning for the project included a delay while the state first established an Erosion Control Line. After six weeks of dredging, Delray’s first dredge and fill project to create a wide beach was finally completed in July 1973 by C.F. Bean Inc. of Louisiana. The dredge pumped sand to the beach from half a mile offshore via large pipes.

As expected, the Town of Gulf Stream benefitted by summer migration of sand from the Delray project. The original study completed by Art Strock & Associates was relied on for similar projects in Hobe Sound, Palm Beach, and Ocean Ridge. Delray Beach City Manager Eldon Mariott was credited with guiding the planning and completion of the project, while County Commission Chairman George Warren helped at the county level, and U.S. Congressman Paul Rogers helped on the federal level.

Most importantly, Robert M. Ganger was a problem-solver who used persistence, providing classic evidence of how government can be successful. With inspiration from General Carter, he organized a common-sense plan to restore beaches, including the home he bought with all his retirement savings. With a small group of committed people, he educated decision makers about a sustainable way to protect oceanfront property, both public and private.

Timeline for Delray Beach Dredge and Fill Projects

(sand volumes are approximate due to the use of cubic yards or cubic meters)

1973: First fill project of 1,400,000 cubic yards of sand dredged onto 2.5 miles of beach.

1974: Vegetation planted on the dune to help prevent erosion.

1977: Erosion Control Line update by the State of Florida.

1978: Second fill project of 500,000 cubic yards of sand added, with additional vegetation planted on the dune.

1984: Third dredge and fill project of 994,000 cubic yards of sand.

1992: Fourth fill project added 914,000 cubic yards of sand.

2002: Fifth fill project added 940,000 cubic yards of sand.

2005: Sixth fill project added 191,000 cubic yards of sand.

2013: Seventh fill project added 813,000 cubic yards of sand.

2020: Eighth fill project added 325,000 cubic yards of sand at the south end of the beach.

Total fill material placed on Delray Beach has been more than six million cubic yards over a 50-year period: an average of 120,000 cubic yards per year.

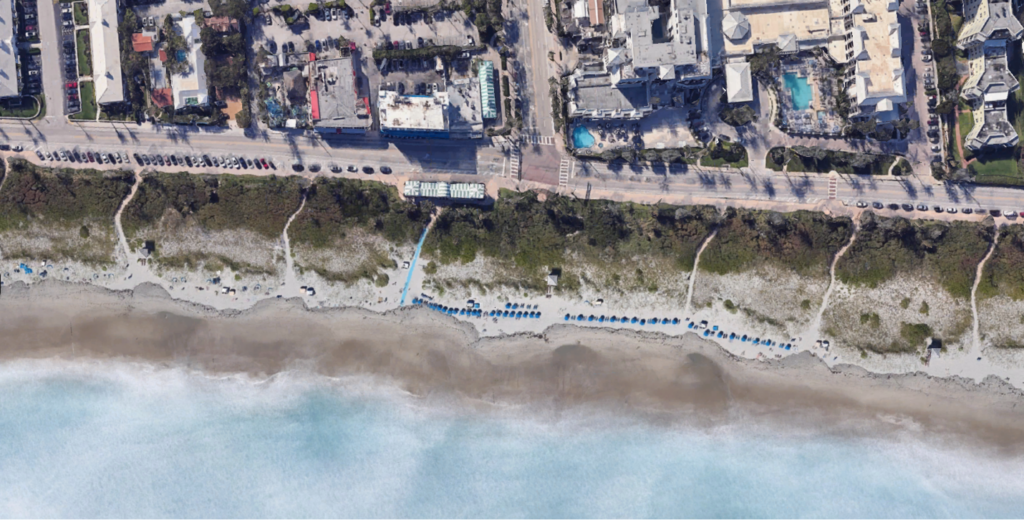

Delray’s Beaches: Present and Future

As a result of these fill projects, Delray Beach enjoys one of the healthiest beach and dune systems in South Florida. This is more impressive because Delray Beach is in an area of naturally high-volume sand movement. Numerous studies show the economic benefits of Delray’s engineered beach far outweigh the cost, with extraordinary payback. One of the key components of this success is the natural erosion control provided by the vegetation planted in the dune area, and recent efforts are adding a wider range of native dune plants to enhance diversity as more than 100 species are native to local oceanfront dunes. Offset pedestrian trails through the dune divert waves during storm surges, and beach patrol officers educate beach goers about protecting the vegetation.

As Delray Beach residents look to the future, they rely on science to sustain their beloved beach. Understanding the natural processes through oceanography becomes a significant part of the planning, so the following facts help in decision making:

- Most experts agree that replacing eroded sand with suitable dredged material from offshore, or with quality sand moved to the beaches from inland by trucks, is the most sustainable method of erosion control.

- Most experts agree that armoring the coast with hard structures causes additional erosion. Hard structures can save infrastructure but will result in loss of beach and starve downdrift beaches of sand, often resulting in legal action.

- Florida’s east coast has 19 inlets, up from just 11 in 1900. Many of those inlets now have longer jetties, further disrupting the natural movement of sand.

- Natural sand movement on local beaches is in a narrow ribbon, from the dune line to about 25 feet of depth. Sand in even deeper water is typically finer grain material, was never on the beach, and when placed on the beach does not make as stable a beach.

- Tidal flow through inlets during outgoing tide moves sand out to sea, especially during times of high seas. Sand is also moved into inlets during incoming tide, especially during times of high seas.

- The term “dredge and fill” is the most common description used by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for beach fill projects. Since these projects can have adverse effects on the coastal zone, “dredge and fill” may be more accurate than “nourishment”.

- Finding beach-compatible sand offshore is very difficult and is becoming more expensive. Many ocean engineers have stated that Southeast Florida has already run out of suitable material immediately offshore. The Army Corps of Engineers has begun to identify material outside state waters in federal waters, well east of St. Lucie County, which may someday be moved via barge to South Florida beaches. Many truck-haul projects from inland locations have supplied Palm Beach County beaches with suitable material to re-build dunes and beaches, but this sand must be washed in advance to remove fine particles that can cloud the ocean water, killing coral and other sea life.

- The grain size of typical native beach sand in Palm Beach County is about .46mm while sand dredged from offshore has a grain size of about .20mm. Polished seashell fragments constituted a large part of native beach sand in Delray Beach. The shell fragments drop out of suspension quickly, resulting in clear ocean water even during high seas. On the east coast, this is unique to Palm Beach County, since areas to the north have material deposited by rivers, and areas to the south have finer material from coral particles. Replacement of native sand with offshore material has gradually changed the nature of Delray’s beach and ocean conditions.

- One very important consideration goes further than the grain size of sand. “Durabilty” describes whether large grains of sand disintegrate in breaking waves when placed on a beach. Wave action that disintegrates sand results in cloudy water which can smother reefs and stop sunlight from reaching corals, degrading the ocean environment. Polished seashell fragments, historically a big part of Delray’s beaches, are very durable and add significantly to the unique quality of local beaches. In 2024, Delray’s beach is mostly made of material dredged from offshore, with some native beach sand mixing in from the north. Frequent projects to add material have resulted in a wide beach, more stable than most in the area.

Legal and Environmental Experts Weigh In

An example of legal action requiring more sustainable fill projects happened in 2008. Ten miles north of Delray, the Town of Palm Beach planned to dredge and fill the “Reach 8” area, just north of the Lake Worth pier. A nearby fill project in 2005 had failed, and Surfrider Foundation filed suit against the Florida Department of Environmental Protection when DEP approved the Reach 8 project. The trial lasted three weeks, ending in October 2008. Attorney Jane West, representing the petitioner, summarized the verdict: “The judge clearly grasped the significance of the geological and biological systems in this area and their rarity. His ruling focused on overwhelming data from numerous experts that supported the denial of this permit.”

In a previous project, the Town of Palm Beach dredged and filled the “Reach 7” area, just to the north, costing taxpayers tens of millions of dollars. Not only did the poor-quality material placed on Reach 7 cause substantial environmental harm to the local coastal resources, it also quickly eroded away. With the Reach 8 plan, the town of Palm Beach proposed dredging and filling 700,000 cubic yards of material, covering seven acres of near-shore reefs, which would have killed marine life and destabilized valuable recreational uses of the area. Rob Young, Director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University, and an expert witness in the case, expressed admiration for the judge’s ruling: “Judge Meale took a very hard look at the “Genesis” computer model used to predict where the sand would go, and he strongly criticized its use. This same model is used all over the country for the design of beach fill projects. The Judge’s ruling is a serious indictment of that practice.”

“This is a tremendous win for Florida’s Beaches,” said attorney Martha Collins. “To our knowledge, this is the first time that any court in the U.S. has flatly rejected the permitting of an approved beach nourishment project due primarily to the expected negative environmental impacts. It is time for the State of Florida to re-examine its policies on beach management.”

In 2016, coastal engineer Dr. Lindino Benedet published a paper about the success of the Delray Beach erosion control projects. One of his findings explained an unintended but fortunate consequence of Delray’s first dredge and fill project, and that benefit continues today. The dredging of 1.4 million cubic yards of fill for that project left two, half-mile-long “borrow pits” about a half-mile offshore. Those pits are about 80 feet deep, 40 feet deeper than the surrounding sandy ocean bottom. Since those pits are beyond the “zone of closure,” they are substantially the same depth as when they were dredged 50 years ago. Long period groundswells that travel over the pits are focused, creating one of the best surfing areas in Florida. This unique recreational resource helps support six surf shops and four surfing schools, enhancing Delray’s most important economic asset.

On May 29, 2024, Delray Beach was voted the Best Beach in Florida in USA Today’s Readers’ Choice 2024 “10 Best Awards.” While thousands of people enjoy Delray’s beach, most have no idea that it had nearly been lost. The beach in Delray has averaged more than 100 yards wide for 50 years. Native vegetation on the restored beach helps to hold the sand. Humankind solved the problem, and this success has been one of the most important developments in South Florida history.

Recognizing the importance of dealing with Climate Change and higher sea levels, the City of

Delray Beach designated its first Sustainability Officer in 2009. Direct public engagement is

encouraged with a 2024 Climate Action Planning Survey that residents are asked to submit.

For more information on the history of the beach, the Delray Beach Historical Society offers a self-guided beach walk about Delray’s famous oceanfront includes detailed information, including several historical markers.

For questions or comments, email the Archive Coordinator! [email protected]