By Kayleigh Howald

South Florida has played host to numerous artists and writers for well over 100 years. Our landscapes, varied cultures, and tropical weather inspired painters like Laura Woodward in the 1880s and the Highwaymen of the 1950s, as well as authors like Zora Neale Hurston, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Ernest Hemingway, and Tennessee Williams. While Key West, Miami, Tampa, and even Gainesville come to mind when we think about artistic and literary communities in Florida, our Village by the Sea was a cultural hub for creatives in the early 20th century.

Many enjoyed Delray’s small-town charm and tranquility, in addition to its proximity to the winter social scene in Palm Beach, Miami, and neighboring Gulf Stream. One could even argue Delray’s reputation as an artist and writer colony helped sustain the tourism industry throughout the 1930s and the Great Depression. Since November is National Novel Writing Month, we thought we would celebrate by sharing the history of some of Delray’s literati.

Emmett Campbell Hall

Unlike Delray Beach’s other writers, Emmett Campbell Hall did not come to Florida to write, but to escape writing. Born in 1882 in Talbotton, Georgia, Hall moved to New York in the early 1900s, where he became a screenwriter. Between 1910 and 1917, he wrote nearly 70 silent films, many of which focused on Confederate soldiers and stories during the Civil War including “Red Eagle’s Love Affair,” “A Reconstructed Rebel,” “Stonewall Jackson’s Way,” and “His Trust: The Faithful Devotion and Self-Sacrifice of an Old Negro Servant.” Hall wrote several films with Edwin S. Porter and D.W. Griffith, the two most famous directors at that time.

While many of Hall’s films were not necessarily runaway successes, his work was culturally significant. For example, in 1912, Hall wrote For His Son, a film about a doctor who spoils his son, but can no longer afford to give him more money. So, he invents a soft drink with cocaine called “Dopokoke” to raise money. While the drink becomes popular and makes them both rich, chaos ensues. The son becomes addicted to the drink and eventually begins injecting cocaine, ultimately leading to a tragic ending. It is one of the earliest films to address substance abuse disorder.

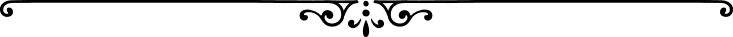

By 1918, Hall became disillusioned with the film scene. He was overworked and underpaid. He decided to relocate to Florida and become a farmer. Hall also quickly became involved in the state’s real estate boom, purchasing several tracts of land between Federal Highway and the Intracoastal Waterway and developing numerous subdivisions. In 1925, his father, John Hall, commissioned Samuel Ogren to build a house on Federal Highway, often known as the Falcon House.

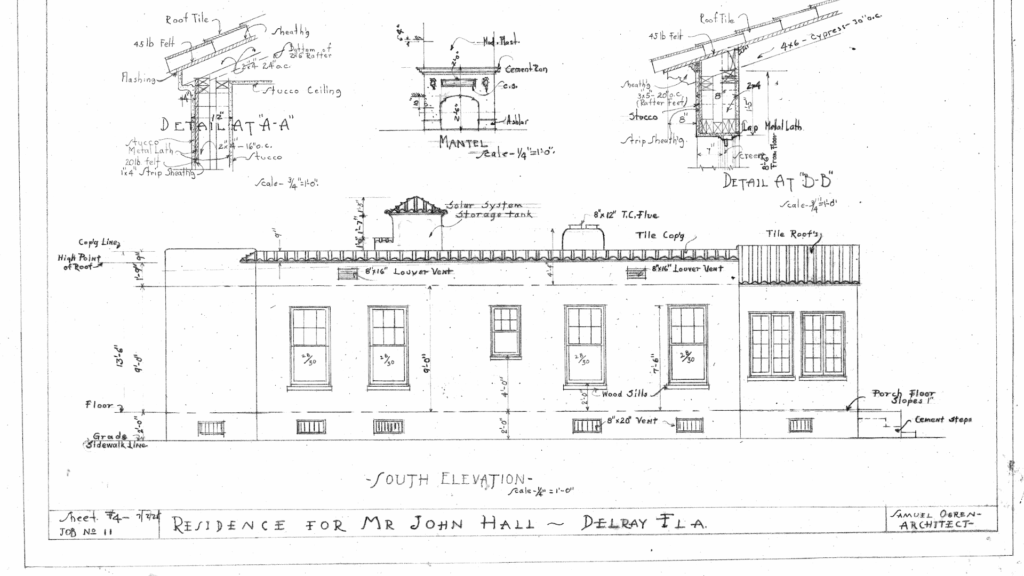

Hall did not give up on the movies entirely. In 1925, he built the Delray Theater, a Mediterranean Revival style building. It was the first air-conditioned theater in Delray and had a rooftop dance floor. To cool the theater, fans blew over a large concrete pit filled with 500 to 600 pounds of ice to create breezes over patrons. The Delray Theater was located on Federal Highway, or SE 5th Avenue, and was demolished in the 1960s.

Nina Wilcox Putnam

Born Inez Coralie Wilcox in 1888, Nina Wilcox Putnam was homeschooled by her father, Marion Wilcox, an English professor at Yale and editor for both Harper’s Weekly and the Encyclopedia Americana. She published her first short story in the New York Sunday Herald when she was 11-years-old. In 1907, she married New York publisher Robert Faulkner Putnam and the couple had one son. Although Robert Putnam died during the Spanish Influenza pandemic in 1918, she kept his name for the rest of her life (despite marrying three more times).

Putnam was a unique woman with an eclectic list of accomplishments. She drafted the first U.S. Individual Income Tax Return for the IRS, also known as a 1040 form. She supported the Aesthetic Movement, which advocated for dress reform during the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Putnam was also the member of the Heterodoxy Club, a dining and debate club for “unorthodox women” founded in Greenwich Village in 1912. Other members included Margaret Sanger, poet Amy Lowell, anarchist Emma Goldman, suffragist and co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union Crystal Eastman, and disability advocate Helen Keller.

She was a prolific writer, penning romances, westerns, musical comedies, and horror. She wrote 24 books between 1912 and 1962 and created two comic strips: Sunny Bunny and Witty Kitty. She also wrote numerous articles for the Saturday Evening Post and her syndicated column, “I and George,” appeared in 400 newspapers. Several of her stories were also turned into films, including her first book In Search of Arcady. The most famous film based on Putnam’s work was The Mummy (1932), starring Boris Karloff. Originally, however, Putnam and screenwriter Richard Schayer wrote a nine-page treatment about Alessandro Cagliostro, a real-life 18th century Italian occultist and conman who promoted Egyptian Freemasonry. Through her books, comics, and screenwriting, by 1942, Putnam had earned $1 million from her writing and was considered one of the highest paid writers in North America.

Putnam primarily lived in New York, but she traveled all over the world. She stayed in Nice, France for a time, owned a house in Hollywood, California, and even bought a castle in Spain. Putnam also lived and worked at the Galloping Tiger Ranch on North Swinton Avenue during the 1920s, located where Trinity Lutheran Church is today. Like many others during the 1920s, she bought the property sight unseen because it was “such a jungle.”

According to an article in the Miami Herald, Putnam was “essentially a country person. I always prefer to live in a small town and on the outskirts at that.” Still, she was very involved in the community, even donating $100 toward the Delray Beach Library. She also allegedly had the first swimming pool in Delray Beach.

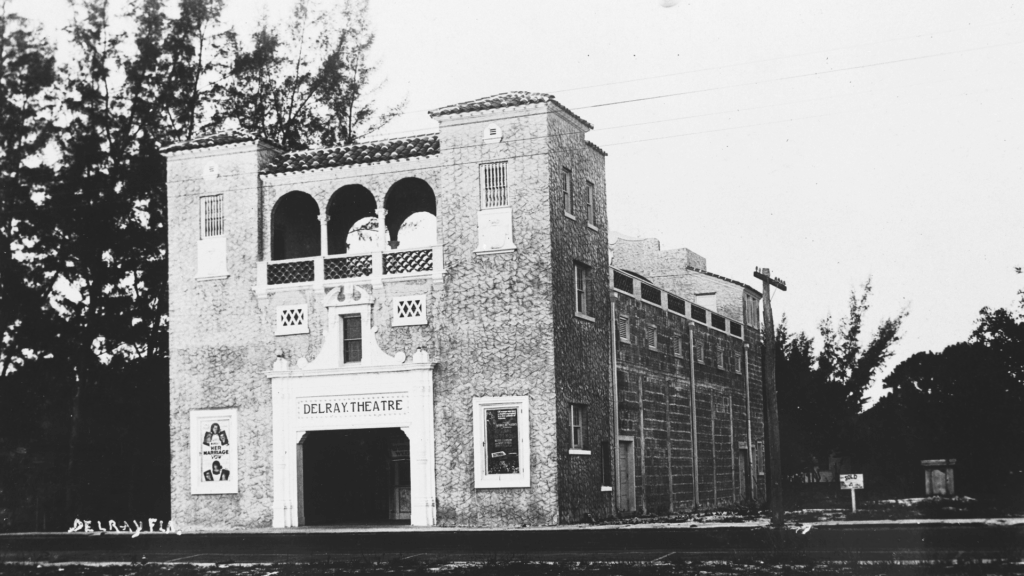

Edna St. Vincent Millay

One of Delray’s most famous writers has, arguably, the most tenuous connection to Delray Beach, having spent only one winter here: poet and playwright Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Millay, not unlike Putnam, was ahead of her time. A nearly lifelong pacifist with progressive political ideologies and multiple love affairs with both men and women, she was often described, according to the Edna St. Vincent Millay Society, as “a talented, spirited, at times overly dramatic adolescent who loved spending hours by the sea and learning the names of flowers, plants, and medicinal herbs from her mother,” Cora Millay, a nurse. Growing up in Maine, she won poetry contests from a children’s magazine, and later wrote and starred in her high school plays and edited the school literary magazine.

In 1911, when she was 19, Millay submitted her poem “Renascence” in a poetry contest. While the poem did not win, in 1912, it appeared in The Lyrical Year, a poetry magazine, under the name E. Vincent Millay. People immediately took notice and were shocked to find out she was a young woman. In a note to the editor, poet Arthur Ficke (who became Millay’s lifelong friend), wrote, “No sweet young thing of twenty ever ended a poem where this one ends: it takes a brawny male of forty-five to do that.” Millay responded, “I simply will not be a ‘brawny male’ . . . I cling to my femininity!” According to the Edna St. Vincent Millay Society, Millay later represented the “rebellious spirit” of the post-World War I generation, also known as the Lost Generation, and became their spokesperson for women’s rights and social equality. In 1923, she won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for her collection, Ballad of the Harp-Weaver. She was the second person to win that specific prize.

Millay traveled throughout the 1920s and 1930s. She and her husband, Eugen Jan Boissevain, a Dutch coffee importer (previously married to suffragist Inez Milholland) initially lived in Manhattan, but Millay could not concentrate on her work there. She explained: “I cannot write in New York… It is awfully exciting there and I find lots of things to write about and I accumulate many ideas, but I have to go away where it is quiet.” They moved to a quiet berry farm in upstate New York they named Steepletop. The farmhouse, barn, outbuildings, and 435-acre property cost $9,000. In addition to gardening and writing, the couple hosted parties where “the flowers were watered with gin,” held tennis tournaments, and put on plays with touring groups of actors in an amphitheater they set up on a hill above their home.

In 1934 through March 1935, they traveled to the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Cuba, Islamorada, and Boynton Beach. This trip to visit Boynton resident William L. Brann, an advertising executive and thoroughbred horse breeder, may have inspired their decision to rent a house in Delray Beach in December 1935.

Millay briefly described her experience in Delray in letters to her friends and editor that winter. For example, she did not enjoy some of the area’s fauna. To editor and poet George Dillion, she wrote, “It is obvious that Harper & Bros. are trying to kill us, so that they’ll never have to have anything to do with either of us again… Only sent me one set of proofs, too… and no return envelope either, such as they always send me – and how the hell am I going to get hold of an envelope, out here among the rattlesnakes and the red-bugs?”

She had other, more positive things to say as well, describing Delray as “Little America.” In one letter, she wrote, “We’ve been here since the first of December, in a cute little furnished house with all the conveniences except one—the water for one’s bath is heated on the roof by the sun, and since there’s never any sun, but only fog and wind and clouds and pouring rain and icy cold weather, there’s never any hot water, except that which one heats on the kitchen stove.” Millay also reportedly stayed at the Seacrest Hotel.

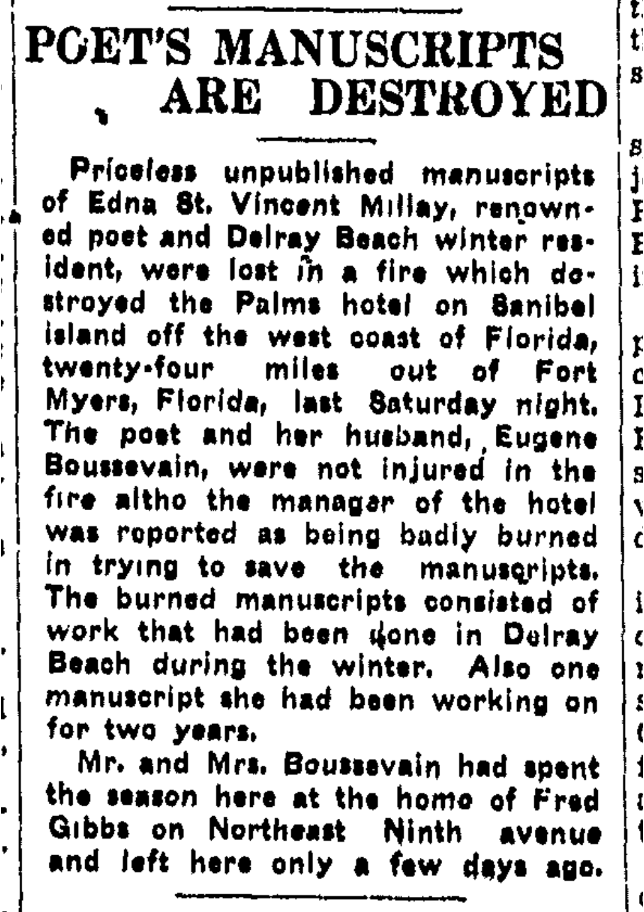

Despite the ice-cold water, Millay was able to work on her poems, which later became the collection, Conversation at Midnight. The original manuscript for that collection, however, was lost in a hotel fire while Millay and Eugen were in Sanibel. (This news clipping is the only hint we have as to where Millay lived in Delray).

Hugh McNair Kahler and Whitman Chambers

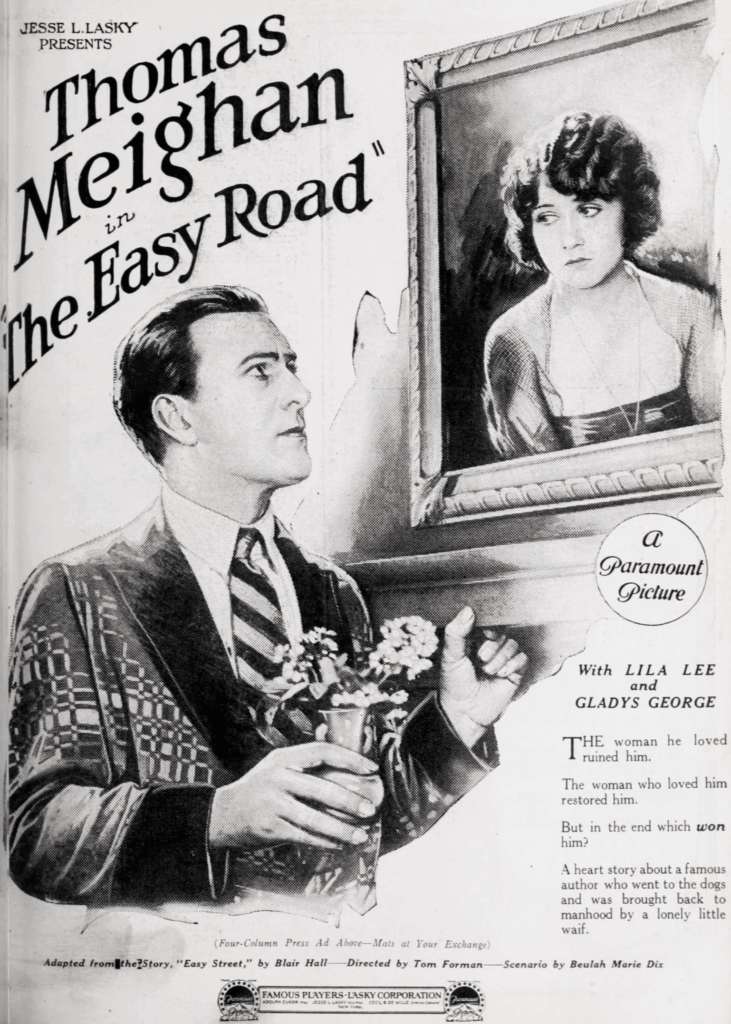

Two other notable writers included Hugh McNair Kahler and Whitman Chambers. Kahler was a novelist and short story writer who sometimes wrote under the name “Blair Hall,” taken from his dorm at Princeton. Kahler wrote approximately 98 stories for The Saturday Evening Post and also contributed to Collier’s, Country Gentleman, Ladies Home Journal, and McClures. At least eight of his articles and short stories were adapted into silent films, including Alias Mrs. Jessop (1917), The Silent Sellers (1917), The Rescue (1917), The Easy Road (1921), Fools First (1922), and The Little Giant (1926). In the 1930s, Kahler stayed in the Seacrest Hotel and rented an office at the Arcade Building. Kahler reportedly paced while working and developed his dialogue by reciting it out loud, much to the annoyance of a local obstetrician.

Novelist, journalist, and screenwriter Whitman Chambers also wintered in Delray Beach during the 1930s. Chambers served as a naval officer in World War I and spent seventeen years as a screenwriter for Paramount, United Artists, Universal, and Warner Brothers. He used his experience as a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner, the San Francisco Bulletin, and the Oakland Enquirer to write a slew of mystery and suspense novels between 1928 and 1960, such as The Coast of Intrigue, Murder for a Wanton, Dry Tortugas, and Bring Me Another Murder.

Theodore Pratt

Theodore Pratt is best known for his Florida novels, including The Barefoot Mailman, The Flame Tree, The Big Bubble and The Big Blow. Pratt began his writing career as a journalist and columnist, writing for the New York Sun and the New Yorker. Pratt and his wife Jacqueline, or Jackie, traveled in Europe and lived in Spain in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but were forced to leave after Pratt wrote some rather scathing things about the people of Majorca. Shortly after they returned to the United States, the couple drove from New Rochelle, New York to Lake Worth, where they lived from 1934 to 1946.

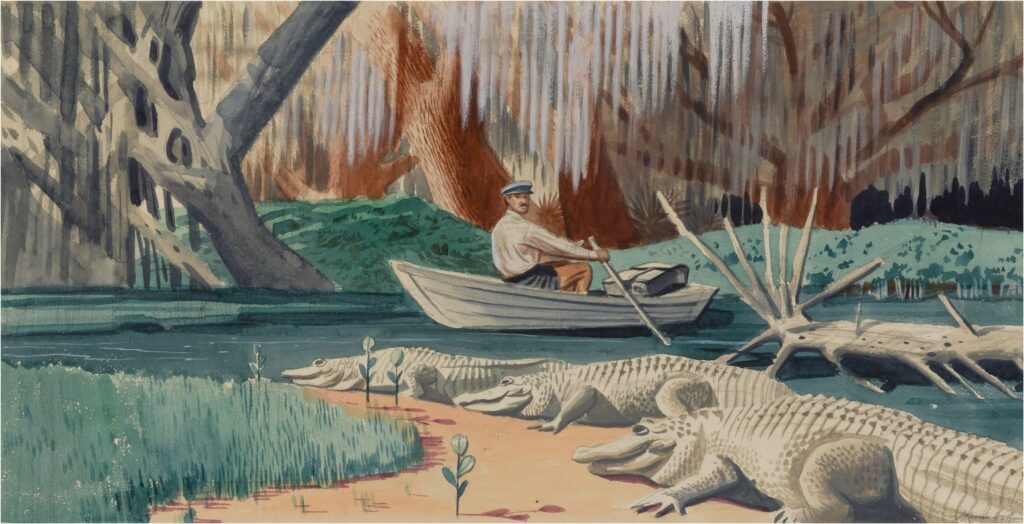

Pratt quickly embraced Florida and immersed himself in every aspect of Florida life to better write and understand his characters. According Geoffrey Lynfield in the Spanish River Papers (Boca Raton Historical Society), Pratt traveled to every “Cracker Holy Roller meeting he could find, every cockfight, and old-time medicine show. He went on fishing trips with the Conch people of the Florida Keys and nuff-gobbed on the steps of country stores. He journeyed to the mangrove coast, juke joint on a ‘high’ night, he attended the back country barbeque and any other manifestation of native Florida to which he could gain entrance.”

From 1936 to 1939, Pratt wrote for murder mysteries under the pen name Timothy Brace: Murder Goes Fishing, Murder Goes in a Trailer, Murder Goes to the Dogs, and Murder Goes to the World’s Fair. The 1937 Murder Goes in a Trailer was set in a trailer park modeled on Briny Breezes. The Pratts even stayed in Briny for a brief period to get the feel for the community and trailer living. In 1946, they moved to an Addison Mizner-designed home in Boca Raton where he completed his Florida trilogy. In 1958, they finally moved to Delray Beach in a secluded house near Barwick Road.

Even before his death in December 1969, Pratt was considered the Literary Laureate of Florida, especially for The Barefoot Mailman. Pratt even wrote the foreword to Pioneer Life in Southeast Florida, written by actual barefoot mailman and local legend Charlie W. Pierce. Pierce’s family were some of the area’s earliest white settlers and the first residents of the Delray area, living in the Orange Grove House of Refuge. He remains one of our most famous residents, as Pratt is buried in Delray Beach Memorial Gardens Cemetery.

Delray Beach still enjoys a vibrant arts scene today and remains a wealth of inspiration for our town’s writers, poets, photographers, actors, fashion designers, illustrators, sculptors, and more. Each time we create, collaborate, and share our work, it preserves our community’s unique history and encourages all those who come later.

For questions or comments, contact the Archivist at [email protected].