By Kayleigh Howald

Juneteenth, or Freedom Day, commemorates the official end of slavery in the United States. Although enslaved people were declared “legally free” with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, it was not implemented or recognized in Confederate-controlled areas, such as Texas and Florida.

When 2,000 Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay on June 19, 1865 – over two years after the Emancipation Proclamation – the army announced the over 250,000 enslaved Black people in Texas were finally free. In Florida, slavery was officially abolished on May 20, 1865 when General Edward M. McCook declared all enslaved persons free. Emancipation Day became an important annual celebration in Florida’s Black communities, with parades, speeches, and concerts.

When Delray’s first African American residents arrived in the 1890s, many were the children or grandchildren of enslaved people. This includes one of Delray’s most prominent Black pioneers: George H. Green.

According to our research, George Green was born in Gadsden County, Florida in approximately 1870 to Oliver and Sally Green. Either one or both of his parents were formerly enslaved. While records indicate Oliver Green joined the 57th US Colored Infantry in 1863, his mother was possibly enslaved until Emancipation Day in 1865. Sally (or Sallie) Green was born in approximately 1847 in Florida in or near Gadsden County. She was likely one of the 443 female children between the ages of one and five enslaved in 1850 (and one of 2,918 similarly aged enslaved girls in the state).

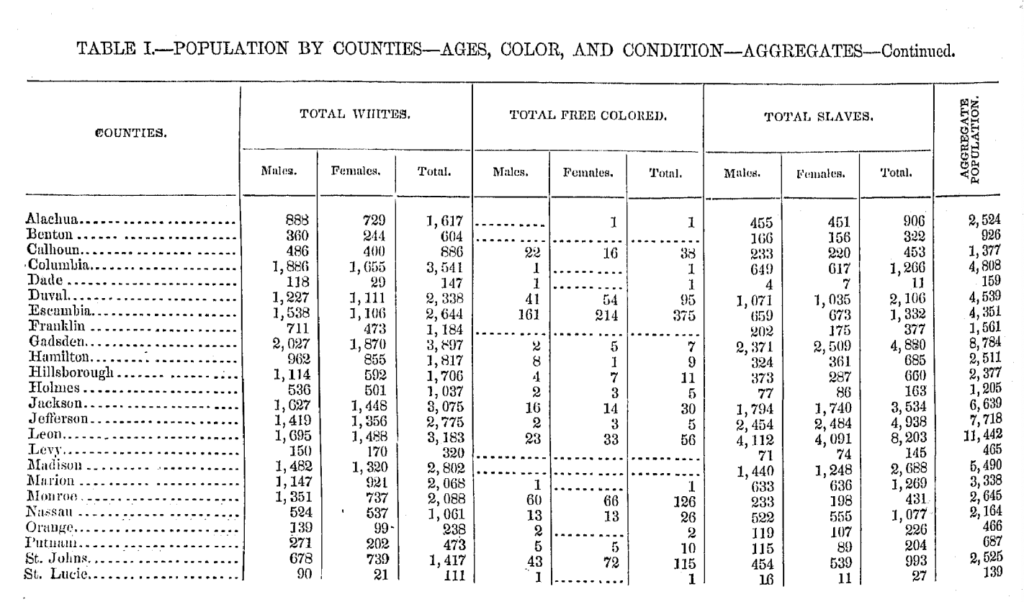

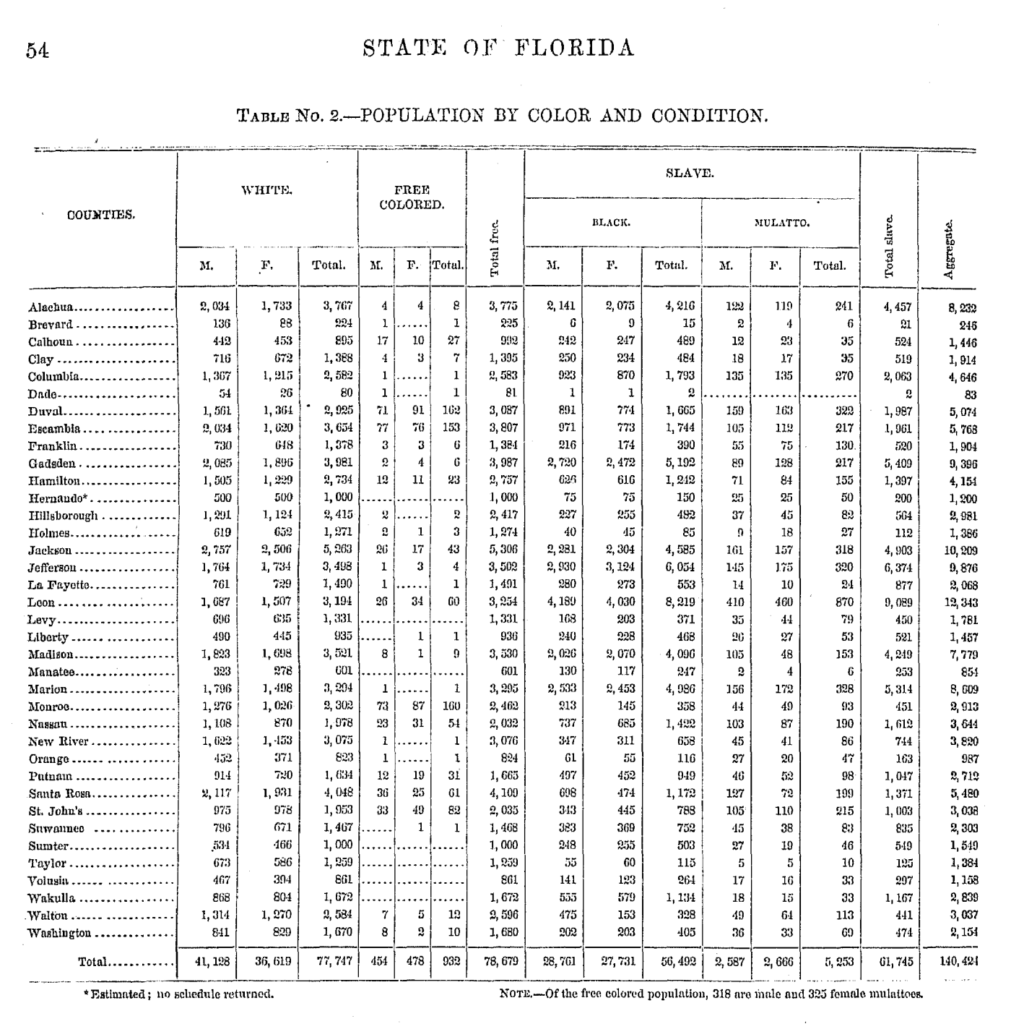

During the 1850s and 1860s, Gadsden County had the third highest enslaved population in the state behind neighboring Leon and Jefferson counties. All three are located along the Florida-Georgia border in the Panhandle. Both large plantations and yeoman farmers grew labor-intensive crops like cotton and tobacco. In the state of Florida, the number of enslaved people increased from 39,310 in 1850 to 61,745 in 1860. In Gadsden county alone, the numbers increased from 4,880 in 1850 to 5,409 in 1860. The numbers, especially compared to the white population, are staggering. Even more so when compared to the number of free Black men and women in the county: 7 in 1850 and 6 in 1860.

By 1885, the Greens had nine children: Catherine, George, John Lee, Eliza, Richard, Robert, William, Betsey, and Mat. Oliver Green was consistently listed in census records as a farmer and, by 1910, he owned a farm in Midway, Florida, a town just northwest of Tallahassee. It is unclear when exactly Oliver and Sally Green died, but their legacy lived on in their eldest son, George.

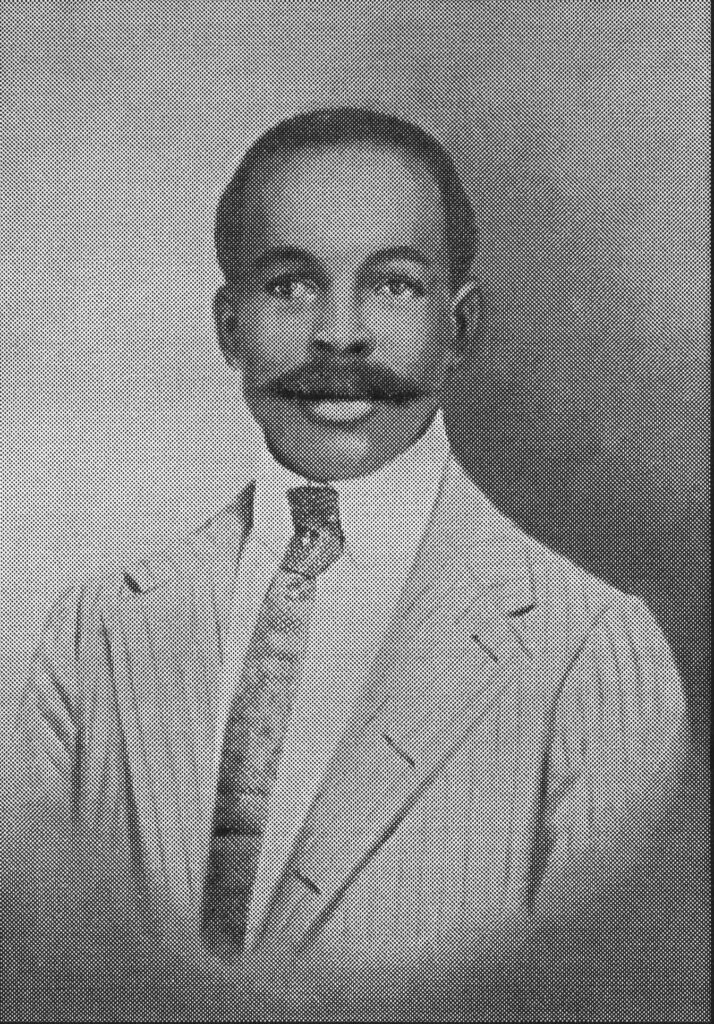

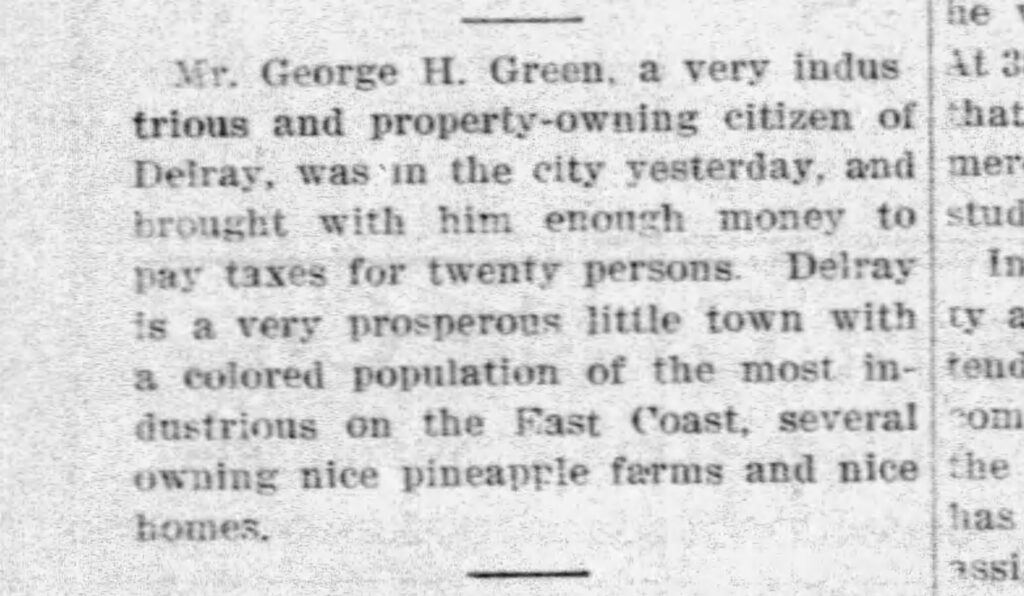

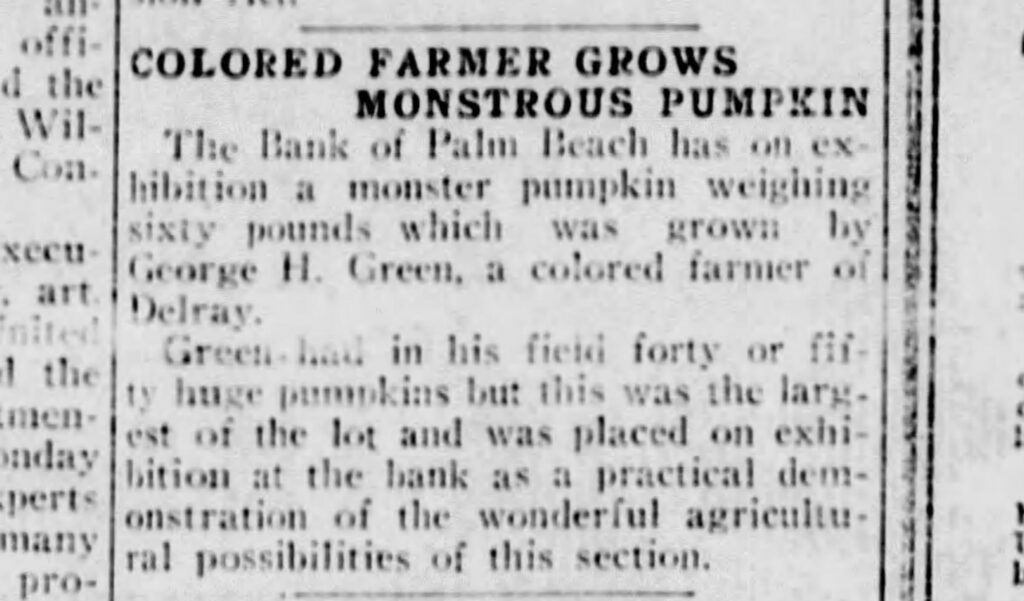

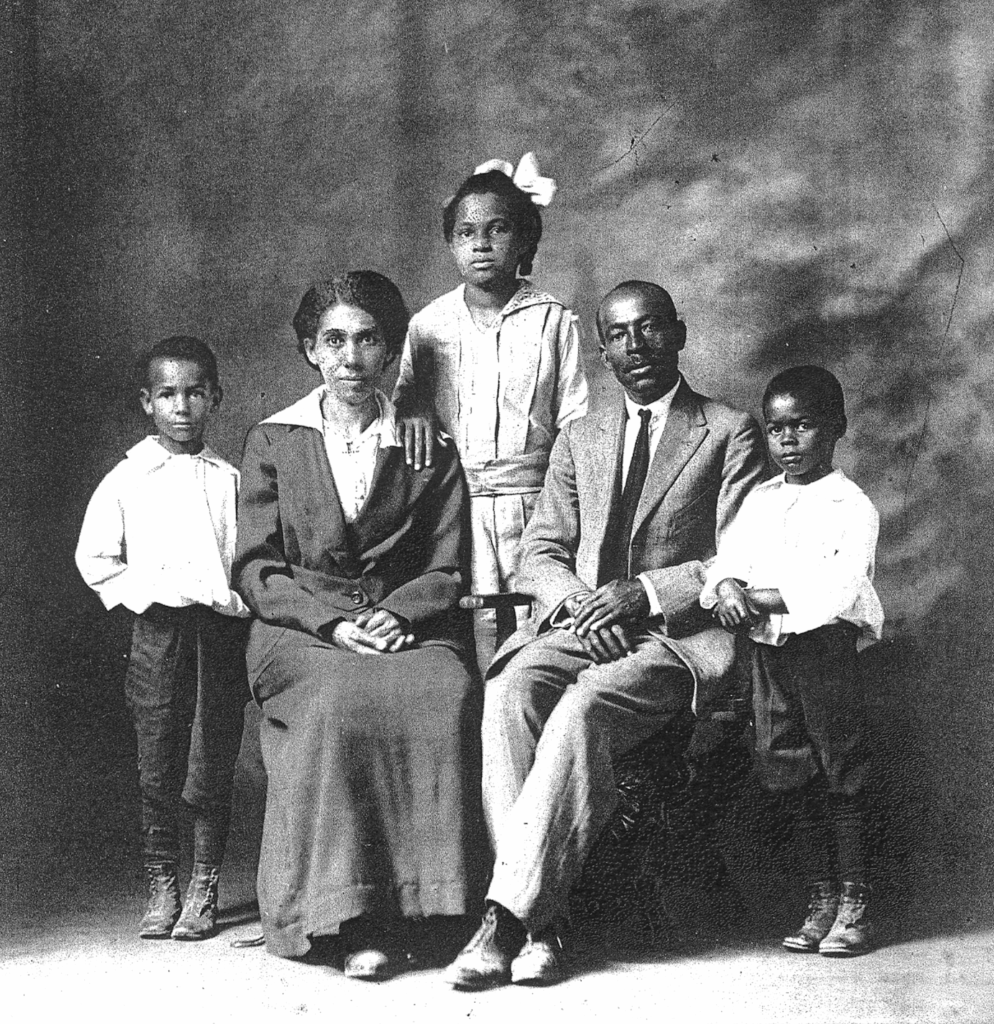

George Green followed in his father’s footsteps and became a farmer in Delray in 1895. He established a farm and homestead on NW Second Street, which stretched as far north as Lake Ida Road. In approximately 1904, Green married Josie Gertrude Jackson of West Palm Beach and they had three children: Garriette, George, and Douglas. In addition to being a successful vegetable farmer and landowner, Green was part owner of a packing house with another Delray pioneer and entrepreneur, Jane Henry Jackson. Records indicate he helped establish Mt. Olive Baptist Church and sold land to both Mt. Tabor Church (now St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal) and St. John Primitive Baptist Church. Green was politically active in the community as well. In addition to running for city alderman during the 1911 elections (and winning sixteen votes from both Black and white residents), Green subscribed to the Crisis, a magazine created by W.E.B. DuBois and published by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). As their portrait suggests, the Greens were one of the most prominent Black families in Delray. There are, however, only a few photographs. Whether the photographs were simply not taken (many African American families, particularly in the early twentieth century, did not have access to handheld cameras or places to develop the film) or they remain in family hands, photographs like the one below are incredibly valuable to archival repositories as they help tell a fuller story of life in our communities.

George Green died in 1927, but Josie remained in Delray Beach until the 1930s. She later relocated to West Palm Beach and died in March 1960. Green’s children – the grandchildren of enslaved people – became prominent members of their communities throughout the United States. Garriette married Dr. Raphael O’Hara Lanier, a history instructor and dean at Tuskegee Institute and Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University (FAMU). In 1946, Lanier was appointed U.S. Minister of Liberia. Garriette was a FAMU graduate, like her mother Josie.

George H. Green Jr. was a teacher at Industrial High School in West Palm Beach, a World War II veteran, and the first Black podiatrist in Florida. He died just two days before his wife Thelma Louise Green in July 1987. Douglas Green also became a doctor. He worked as a urologist at the Freedman’s Hospital, later Howard University Hospital, in Washington, DC. His wife, Bernice Gordon Green lived until the age of 103. Bernice was the adopted daughter of Rev. James Gordon, the first pastor of Trinity United Methodist Church in West Palm Beach. Their son, Warren O. Green served in the U.S. Army as a lieutenant colonel.

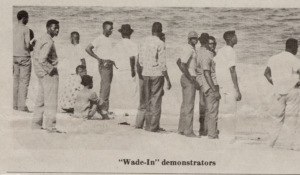

Juneteenth is not only about a single historical moment, but about all the generations that followed. Today, both Juneteenth and Emancipation Day commemorate those who resisted and persisted in a system that was determined to destroy. According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), Juneteenth “marks our country’s second independence day” and “celebrates African American resilience and achievement, while preserving history and community traditions.”

To learn more about George Green, pioneer life in Florida, and the work of civil rights activists in Delray Beach, visit our history exhibits Tuesday through Friday, 11am to 3pm.

For questions or comments, contact the Archivist at [email protected].