By Kayleigh Howald

May is Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month, and to celebrate, we explored the rich history of Yamato, Florida. Yamato was a small community of Japanese expatriates just south of Delray who cultivated pineapples and winter crops, endured anti-immigration sentiment, and helped establish one of the area’s most unique cultural heritage institutions. The rise, decline, and enduring legacy of the Yamato colony represent the fascinating history of immigration and constant adaptability under harsh environmental and social conditions. To understand this history, however, it is important to discuss why and how the Yamato settlers came to the United States.

The Meiji Period

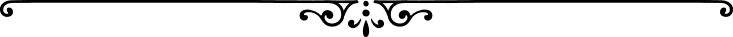

Throughout the nineteenth century, Japan underwent a cultural and political upheaval. In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Tokyo Harbor and all but demanded that Japan open its ports to foreign trade. This ended a centuries-long policy of isolation and strict emigration policies. By 1868, the Meiji emperor was restored as the leader of Japan, ending the Tokugawa shogunate and Japanese feudalism. Japan focused on science, technology, militarism, and industrialism in a dedicated path to modernization. By the 1880s, Japan adopted the American educational system for men and women, established a postal service and newspapers, lifted the ban on Christianity, and used the Gregorian calendar. The Japanese public began wearing western clothing and hairstyles, and there was an increase in demand for western literature.

Japanese Emigration Begins

While the Meiji Restoration benefited some sects of Japanese society, urbanization and industrialization led to agricultural and wage decline among farmers and workers. As such, many young Japanese men sought better economic opportunities outside their national borders. According to the Library of Congress, between 1886 and 1911, over 400,000 men and women emigrated from Japan to the United States and its territories. The Japanese government selected other émigrés from a pool of applicants, usually favoring “ambitious young men with good connections.”

One of those young men was 29-year-old Jo Sakai, a member of an elite samurai family. Sakai received a western education at Doshisha University in Kyoto and converted to Christianity. In approximately 1899, Sakai traveled to New York City and attended New York University’s School of Commerce, Accounts, and Finance. From there, he was introduced to businessmen and politicians from Jacksonville, Florida who were interested in courting Sakai to establish a settlement.

Florida Immigration and the Yamato Colony

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Florida actively recruited immigrants from around the world. While Florida’s land developers often encouraged Europeans from Germany and Scandinavia, the Bureau of Immigration also sought Chinese and Japanese settlers in the hopes of introducing new methods of farming and cultivation. Chinese immigrants traveled to Florida from California or Cuba to work in lumber and turpentine camps. They also opened laundries, small grocery stores, and restaurants in Jacksonville and Miami.

The Jacksonville Board of Trade quickly incentivized Sakai to settle in the state, especially after Sakai expressed early interest in growing lucrative crops, such as rice, tea, silk, and tobacco. Three different counties in northern Florida offered Sakai 1,000 acres of free land, but only the Boca Raton colony materialized. In 1903, Sakai purchased land from the Model Land Company that would soon be known as Yamato, an ancient name for Japan. The following year, Sakai returned to Japan to recruit colonists for the community.

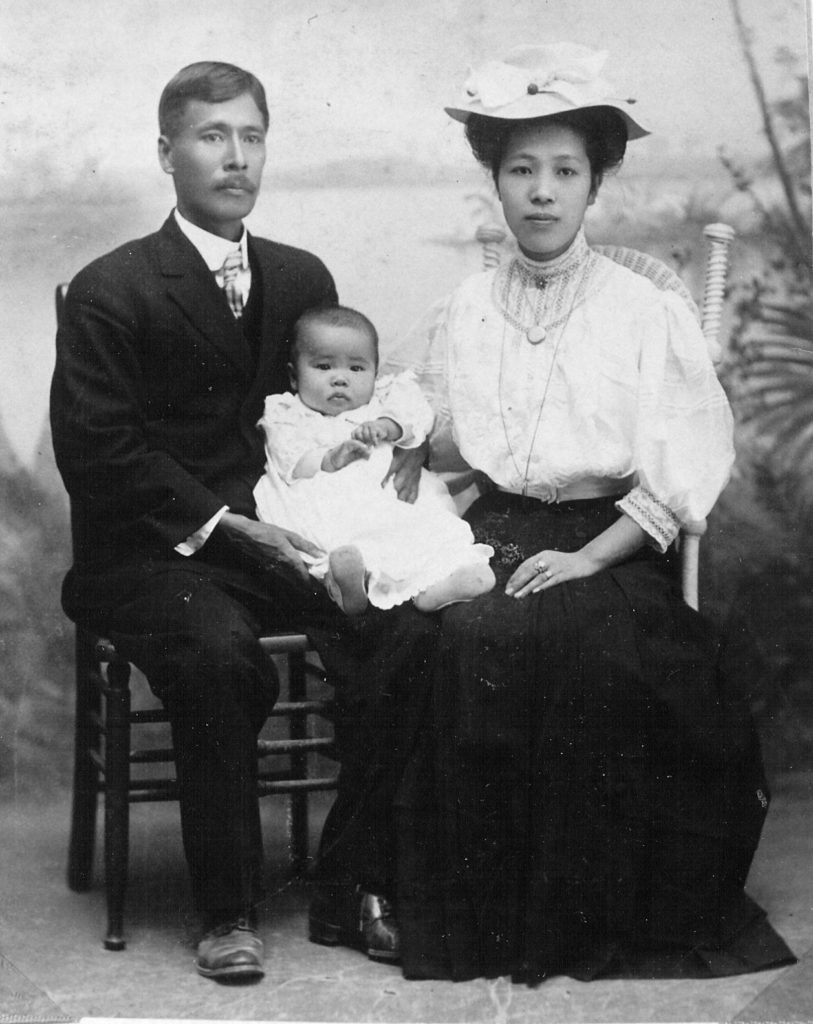

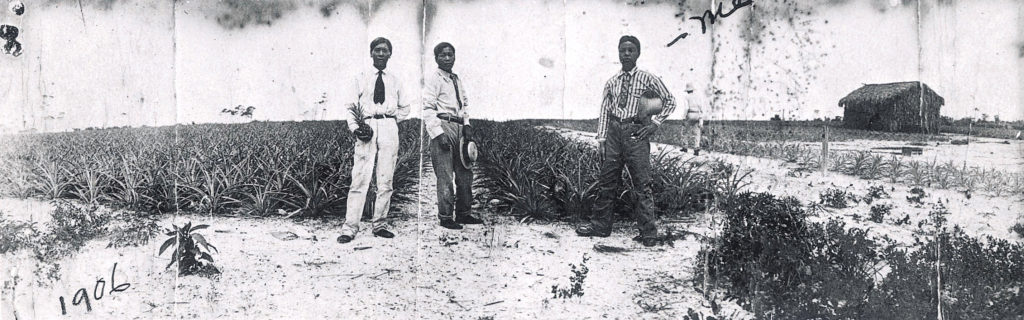

This proved to be more difficult than Sakai anticipated. The Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) was the first roadblock, as potential settlers were unable to obtain exit visas to the United States. Additionally, Sakai was interested in recruiting families to the Florida settlement. The only interest, however, came from unmarried college graduates and businessmen, many from Doshisha University and Sakai’s seaside hometown, Miyazu. By 1906, Sakai had recruited several men to join him and his business partner, Count Masakuni Okudaira, at the Yamato colony. They included Tamemasu “Henry” Kamiya (Sakai’s younger brother), Jinzo Yamauchi, Mitsusaburo Oki (Sakai’s brother-in-law), Aisuke Tsujii, and Sukeji “George” Morikami.

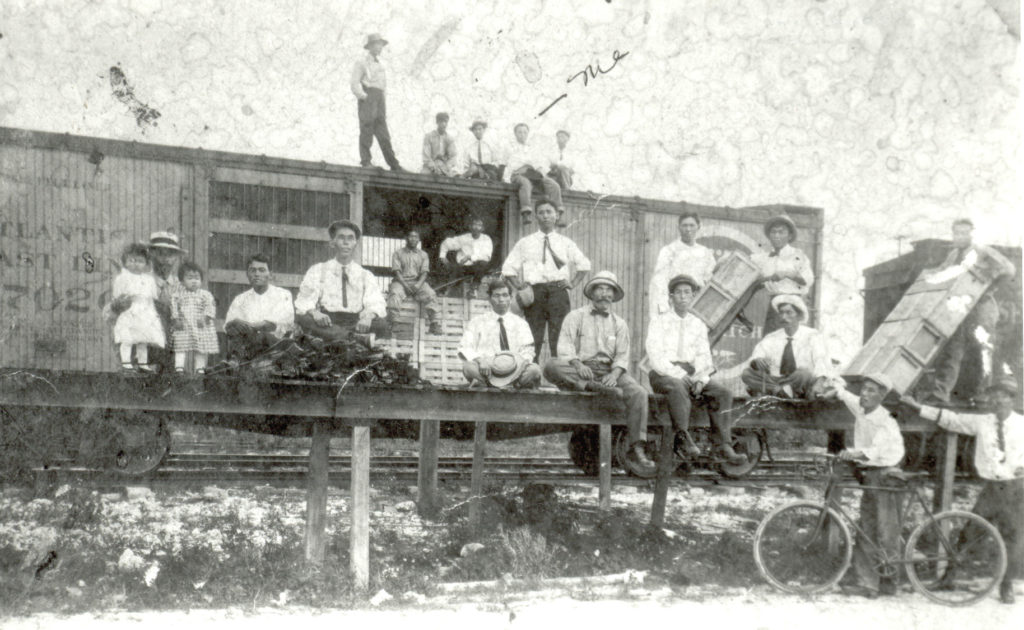

The Rise of Yamato

When the first group of colonists arrived, they were met with unnavigable swamp. They also had to contend with the summer heat and swarms of mosquitoes. While Sakai quickly discovered Florida’s soil and climate were not conducive to growing tea or silk, he found the neighboring Keystone Plantation flourishing with pineapples. After purchasing the plantation from W.W. Blackmer, the Yamato colony reported successful harvests of pineapple crops, along with tomatoes and green peppers. According to oral histories, the colonists also hired African American and Bahamian workers to assist with developing the farms and relied heavily on their expertise as farmers in Florida’s sandy soil.

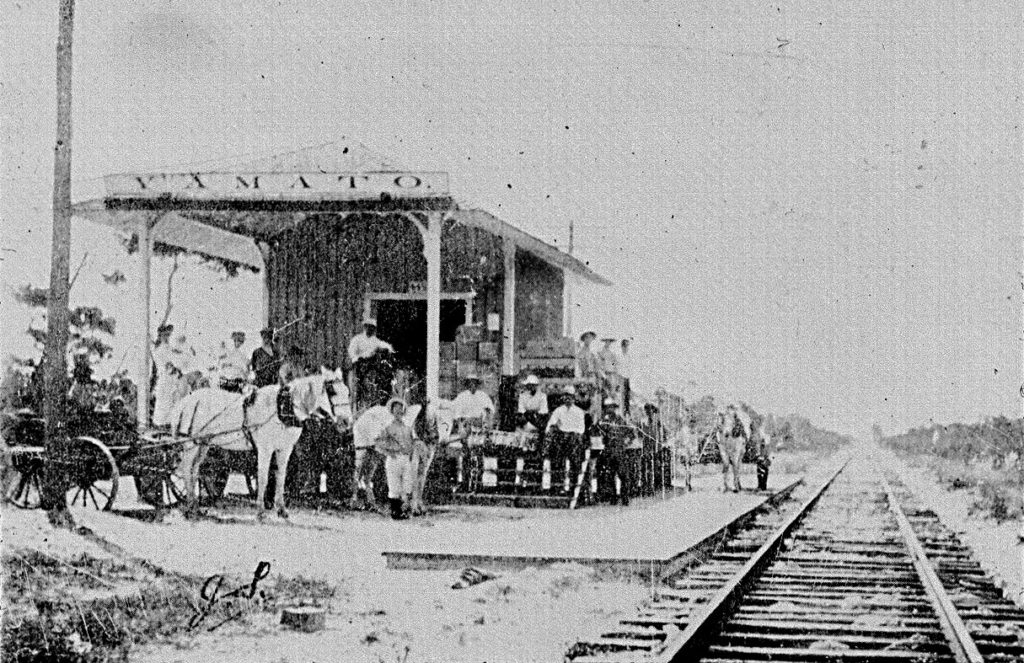

Despite growing contempt against Sakai (and several settlers abandoning the colony), others from the Miyazu area traveled to the United States to join Sakai at Yamato, such as Hideo Kobayashi, Riichi Morita, and Shiboh Kamikama. Others, like Akila Hada Oh-Nishi and F. Tahara, were recruited in New York. Women also joined the colony, many of them as newlyweds. Several émigrés raised families at Yamato, leading to the construction of a one-room schoolhouse where children attended first through eighth grade. Soon Yamato had its own railroad depot and post office, both signs of a thriving town.

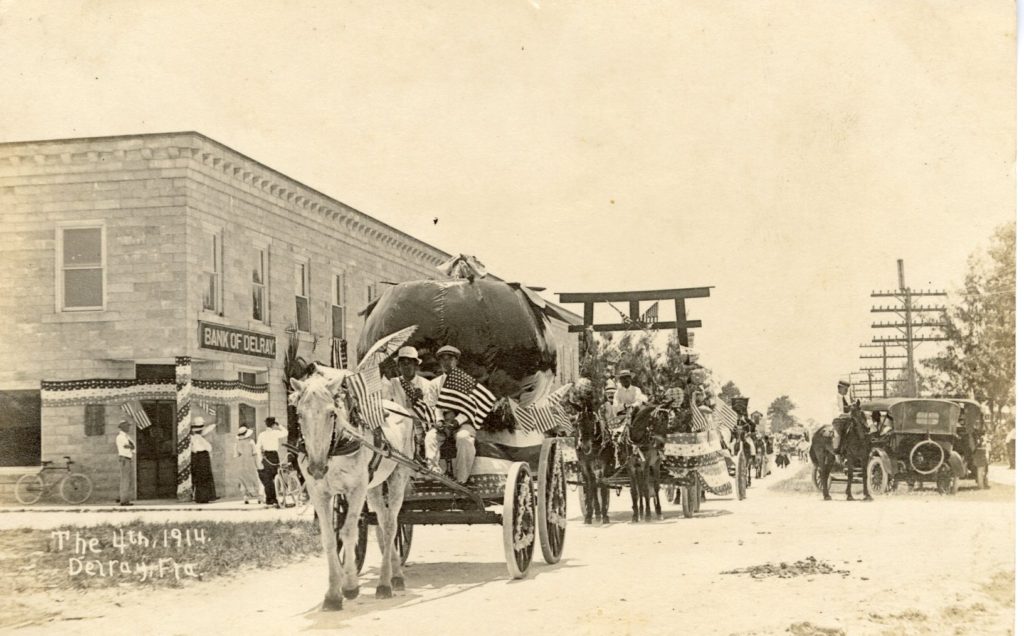

Yamato Colonists in Delray

Men and women alike abandoned traditional Japanese kimono, except on special occasions, but maintained a several Japanese cultural traditions such as preparing miso, installing Japanese-style baths, and playing hanafuda, a Japanese card game. There is, however, significant evidence of transculturation, or the process of cultural exchange, where Japanese émigrés participated in quintessential American traditions while maintaining their unique identity and heritage. In the 1914 Fourth of July parade, Yamato was represented with two large floats featuring a tomato and a replica gateway to a Shinto shrine, both laden with American flags. These selections seemingly sought to bridge the cultural divides and cement the Yamato colony as an important sect of the larger Delray community. Additionally, by the 1920s, children from Yamato began attending Delray Beach High School. Frank Kamiya, for example, played on the varsity basketball team and was a top tennis player in 1926.

Other examples of transculturation between Yamato and Delray Beach include Japanese and Bahamian émigrés fishing together on the rocky beaches near Yamato, and the Kamiya family’s involvement with the Methodist Church. Reverend J.R. Cason conducted the 1929 funeral service for the Kamiyas’ eldest son, Rokuo (after a deadly motorcycle accident), as well as the wedding ceremony for Masa Kamiya’s 1931 nuptials in the family’s Japanese garden.

The Fall of Yamato

A 1908 blight destroyed much of Florida’s pineapple crop, and competition with Cuba decimated the fragile pineapple industry. Although some Yamato settlers quickly pivoted to tomatoes or the booming real estate business, many returned to Japan, or moved further south to Fort Lauderdale and Miami.

Anti-Japanese sentiments and xenophobia in 1912 and 1913 also contributed to Yamato’s decline. According to historians George Pozzetta and Harry A. Kersey Jr., California passed a law forbidding non-citizens from purchasing land, which was directed at Japanese residents. Former Florida Governor William Jennings, who officially endorsed Sakai ten years earlier, publicly invited Japanese émigrés in California to “till the Florida soil,” much to the chagrin of other Florida legislators. Despite multiple attempts to pass legislation preventing Japanese colonists from owning land, no discriminatory property laws were passed in Florida. Yet, this attempt to thwart emigration worked in nativists favor, as new arrivals virtually stopped over the next two decades. The U.S. Postal Service closed the Yamato post office on June 4, 1919, and rerouted their mail through the Boca Raton office.

In 1923, Sakai died of tuberculosis, leaving behind his wife and four children. A year later, Sada Sakai and her children returned to Japan. Following their leader’s death, the colony was never quite the same. Families and single men continued to leave the colony until only four families remained. Their tenure in Yamato, however, would not last long.

Anti-Japanese Policies and World War II

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the mass incarceration of over 110,000 Japanese Americans. Although Japanese Americans in Hawaii and South Florida were theoretically exempt from forced relocation to internment camps, the underlying racism and scapegoating did not escape Yamato’s residents.

On May 16, 1942, U.S. District Judge John W. Holland issued a Petition of Condemnation that allowed the United States to acquire over 5,000 acres west of Boca Raton, later known as the Boca Raton Army Air Field. While the government paid approximately fifty property owners for their land, in many cases homeowners received only half the land’s actual value. For Japanese families, the half-value payment was just one element of unfair treatment. George Morikami and Hideo Kobayashi had their financial assets frozen and were barred from traveling over county lines without prior permission. This was detrimental to Kobayashi, who owned a successful landscaping company and regularly commuted to Fort Lauderdale. After being threatened with internment, Kobayashi relocated his family from Yamato to Fort Lauderdale permanently.

Not all of Yamato’s residents escaped the horrors of internment. Oscar Kobayashi and his family moved to California in 1925, and were later interred in Utah. Henry Kamiya, one of the founding colonists at Yamato, moved to California to be closer to his daughter in 1939. After Executive Order 9066, Kamiya was interned in Manzanar in California’s Owens Valley. Kamiya’s internment was reported in the Delray Beach News as late as April 13, 1945.

Only one of Yamato’s original buildings survived the war. The Sakai and Kamiya home was used as an administrative building on the airbase. The other structures – barns, sheds, and chicken coops – were demolished and utilized as an obstacle/training course. Yamato became one of Florida’s ghost towns, a shell of its former glory.

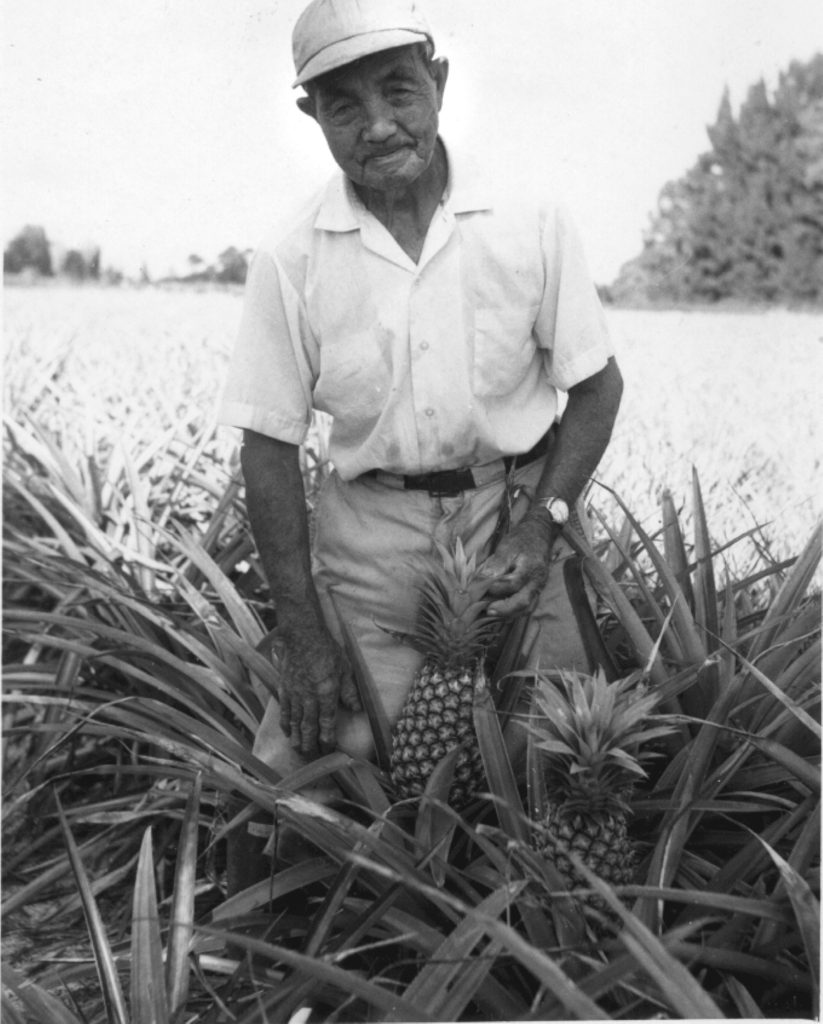

George Morikami and Yamato’s Legacy

George Morikami was one of the few original Yamato settlers who remained in the area. Morikami continued to farm pineapples, tomatoes, and vegetables, and even began a mail order produce business. Over time, Morikami acquired 1,000 acres of land west of the original Yamato colony. In the 1960s, Morikami donated land to the University of Florida to establish an agricultural station and to Palm Beach County for a park. The Morikami Museum opened in 1977 and the gardens were completed in 2001 by landscape architect Hoichi Kurisu. In 1977, Delray Beach further solidified its connections with Sakai and Morikami’s homeland by making Miyazu, Japan its first sister city.

Yamato, Florida only lasted for 40 years, but the impact can be seen and remembered today. Through agriculture and land development, Japanese émigrés at Yamato played an essential role in the cultural and economic growth of southern Palm Beach County. The next time you visit the Morikami Museum or drive down Yamato Road, take a moment to celebrate the pioneers who carved out their living in a new, sometimes hostile land.

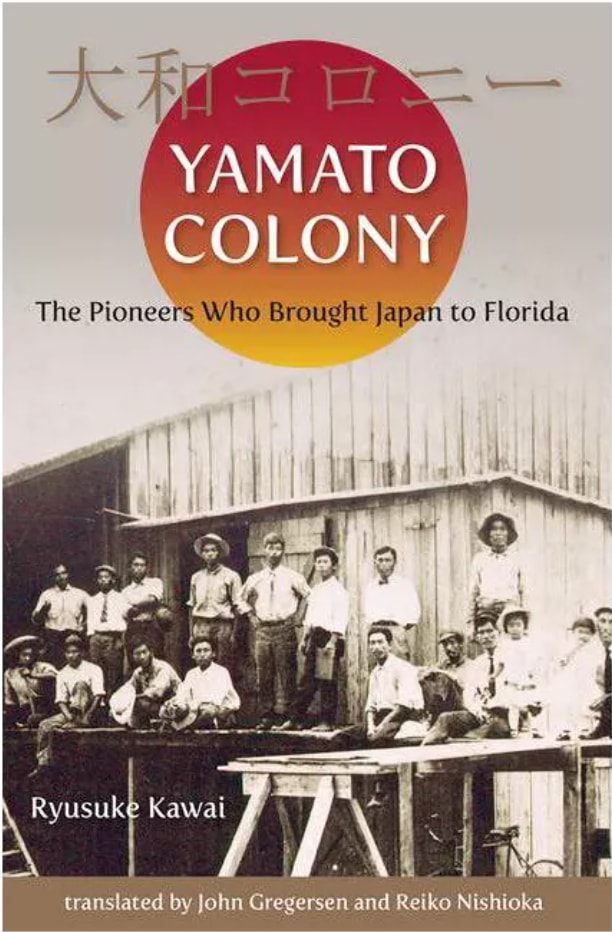

For more information on Yamato, purchase your copy of Yamato Colony: The Pioneers Who Brought Japan to America by Ryusuke Kawai, available in our gift store!

For questions or comments, email the Archivist! [email protected]